Earlier this month, we published our key macro and market themes for 2025. It has also become tradition at this time of year to publish a list of key risks to watch for in the coming 12 months. This can be a fool’s errand: too often, these descend into a long list of what could go wrong (there are never upside risks) rather than assessing the probability of any such event occurring and, more importantly, what the triggers and consequences might be. They are “get out of jail” cards for analysts and of little help to clients.

Many of the events (or “risks”) that could upend our forecasts for 2025 are essentially unforeseeable – episodes like the pandemic and wars. They include wildcards like a major cyber-attack or IT outage, or even a solar strike. At a geopolitical level, any attempt by China to assert authority over Taiwan would have major macro and market consequences, although this is best characterised as a “low probability-high impact" event for the coming year.

What about more conventional macro risks – as well as the probabilities of them occurring and their potential triggers and consequences? Several stand out.

Risk #1: Global trade war

Medium risk; medium-high impact.

Key triggers: Other countries respond aggressively to US tariffs

Our forecasts assume that the incoming Trump administration will impose sizeable tariffs on US imports, but that retaliatory measures by other countries will be designed to avoid escalating tensions with Washington. This would be consistent with the experience during the first Trump administration and should mean that global trade increases (albeit modestly) next year. But we may be wrong. It’s possible that the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration go beyond the 10% universal tariff and 60% tariff on imports from China that we’ve assumed in our forecasts. Carve-outs could be more limited than we have assumed. And, most importantly, other countries could respond in a manner that invites further protectionist measures from the US. The EU and China could respond more aggressively to tariffs, for example by targeting US tech firms. Allowing their currencies to weaken against the dollar could be interpreted by Washington as attempts to “avoid” tariffs and used as a basis for imposing additional protectionist measures. This could end in a global trade war which, while it could take many forms, at the extreme could knock 2-3% off global GDP.

Risk #2: Inflation flares up (again)

Low-medium risk; high impact

Key triggers: Broad increase in tariffs; widespread measures to limit migration; fiscal expansion.

In our central forecast we assume that higher tariffs will push US inflation towards 3% next year. But this is best interpreted as a one-off upwards shift in the level of prices – all other things being equal, inflation will fall back in 2026. This should not cause significant concern at the Fed. And inflation pressures in other major advanced economies should continue to moderate next year, helped by a normalisation of labour markets. But several upside risks remain. One is related to the first risk: other countries could respond to a protectionist shift in the US by raising tariffs aggressively, pushing up inflation globally (although, assuming this is a one-off, the effects on inflation should once again be temporary). Another risk is that measures to curb immigration lead to labour shortages and price pressures in sectors that are dependent on migrant labour. The resulting increase in overall inflation may not be huge – perhaps a few tenths of a percentage point in advanced economies – but it could be enough to slow the pace at which central banks loosen policy. Finally, if plans to tighten fiscal policy in advanced economies are pushed back, the result would be (even) larger budget deficits than we currently forecast – and higher rates of underlying inflation.

Risk #3: Fiscal missteps

High risk; medium impact

Key triggers: attempts to push through additional deficit-financed tax cuts in the US; a sense in markets that fiscal guardrails in advanced economies more generally are weakening

…on which note… several advanced economy governments will run fiscal positions next year that test the limits of the bond market’s patience. We’re assuming that they won’t go beyond this and trigger fiscally induced crises. This could prove to be wrong. France’s fiscal position is an obvious concern – simply forming a government capable of passing a budget next year looks likely to be a challenge. But when it comes to fiscal sustainability, perceptions matter as much as policy. A lot will therefore hinge on what governments say, rather than what they do. If leaders give the impression that their commitment to long-term fiscal discipline is weakening – or that they are determined to force through additional deficit-financed tax cuts or spending increases – then the reaction in bond markets could be quick and severe. A key risk in this regard is that the incoming Trump administration pushes through additional tax cuts financed through higher borrowing, irrespective of market concerns about medium-term fiscal sustainability. This would threaten a sharp rise in bond yields and corresponding tightening of financial conditions. This could be short-lived if the government backs down in the face of market pressure. But if the move in markets is severe, it could still expose hidden vulnerabilities in the financial system. (Exhibit A: Liz Truss and the liability-driven investment crisis.) If a fiscally induced crisis causes something in the financial system to crack then the macro consequences will be much greater.

Risk #4: Stock market bubble bursts

Medium risk; low-medium impact

Key triggers: Disappointing big tech earnings; evidence of slowing AI rollout

Our view is that 2025 will be another good year for US equities, with the S&P 500 on track to hit 7,000. But this is predicated on the idea that – while AI will eventually deliver significant macroeconomic dividends – a bubble keeps inflating around technology stocks as investors attempt to capture the benefits of the technology ahead of them crystalising in the real economy. Our judgement is that the bubble has further to inflate, but it’s possible that it could burst earlier than we anticipate. The bursting of this bubble would be a headline-grabbing event, but its macro consequences could be surprisingly limited. There would be a hit to consumer spending via wealth effects, but this is likely to be relatively small. Business investment would suffer, but this has not been a major driver of US economic growth. GDP may stagnate for a couple of quarters but the recession that many might anticipate from this is by no means inevitable. This would all be cold comfort for equity investors. But if the bubble in stocks bursts in 2025 then it will be the defining market – but probably not the macro – story of the year.

Risk #5: an energy glut

Medium-high risk; medium impact

Key triggers: OPEC+ opens the taps

Most attention is focussed on downside risks to global oil supply: the possibility that Israel could strike facilities in Iran; the prospect of tighter US sanctions on Iran; and the threat of further disruption to shipping lanes in the Middle East. But the greater risk arguably lies in the opposite direction: that there will be a significant increase in global oil supply next year.

For the past several years OPEC+ has constrained supply to try to prop up prices. But this strategy has not delivered the intended results. Brent crude has fallen from around $85pb at the end of Q1 to $73pb today. This is well below the level that key OPEC+ members need to balance budgets and current account positions. (The Saudi Arabian budget currently balances at around $90pb.) This raises the possibility that Saudi Arabia and other influential OPEC+ members might shift from a strategy of trying to prop up prices to one of capturing market share from higher cost producers. In other words, 2025 could be the year in which OPEC+ opens the taps. If this were to happen, oil prices could collapse. The impact on the rest of the world would come through energy prices and inflation. If oil prices were to drop to $60pb, headline inflation in DMs could fall by 0.2%-pts. If they were to fall to $40pb – which sounds extreme but is plausible – then headline inflation in DMs might fall by something like 0.4%-pts. This would give a prop to household real incomes, particularly in large energy importing countries such as those in Europe.

Risk #6: the growth stars align

Medium risk; high impact

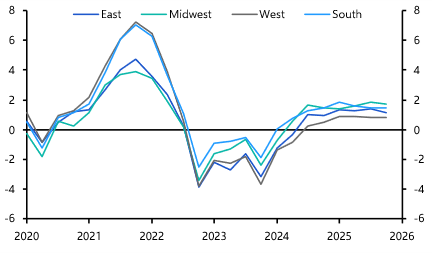

Key triggers: Multiple triggers but would need to be facilitated by faster productivity growth

It is natural for economists to concentrate on the downside risks to growth but 2025 could be the year where the stars align on economic growth. While tariffs are likely to push up inflation in the US next year, inflation in other major economies is likely to head back towards 2% targets. This will alleviate pressure on household real incomes. At the same time, bank lending – which has been notably weak over the past year – could pick up on the back of interest rate cuts. And, while we do not expect major stimulus in China, it is possible that monetary and fiscal support is greater than we anticipate.

With most economies at or close to full employment, a positive growth surprise would require an improvement in the supply-side of the world’s major economies. This is notoriously difficult to anticipate, but is not impossible to imagine. In advanced economies, it would require the pick-up in productivity growth experienced in the US in the first half of 2024 to be sustained and to spread to other major DMs. In China, it would require structural reforms to tackle the headwinds that are weighing on potential growth. Serious efforts to redirect more income to households would represent a significant step in the right direction. Taken together, this would push our forecast for global GDP growth in 2025 from around 3% to closer to 4%. This would require a lot to go right – and for none of the downside risks identified above to materialise. But the possibility of an improved performance in 2025 is a useful counterweight to the pessimism that has emerged in some parts of the commentariat in recent months.

In case you missed it

Don’t miss our wrap-up Drop-In on December’s decisions from the Fed, Bank of England and ECB. Register here for the 20-minute online briefing on Thursday, 19th December.

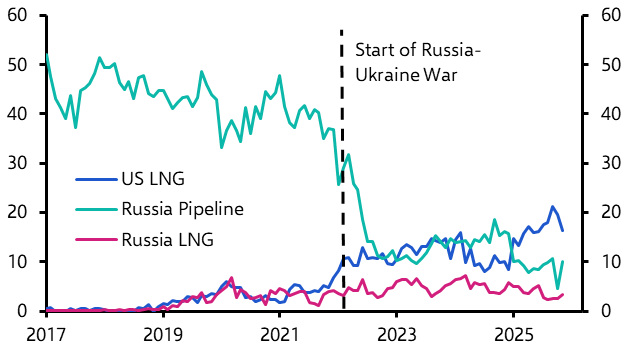

European gas prices could fall by as much as 50% when US and Qatari supply comes onstream, say David Oxley and Kieran Thompkins.

The Russia banking risk component of our EM Financial Risk Indicators is flashing red. Liam Peach explains why economic risks are rising – and how they’re likely to play out.