The agreement by Germany’s likely next coalition partners to reform the country’s strict fiscal rules is both historic and positive: historic because it reflects a shift in attitudes within Europe’s largest economy away from a rigid adherence to fiscal rectitude which has prevailed since the global financial crisis; and positive because it loosens the fiscal straitjackets that has contributed to weak growth in both Germany and the wider European economy in recent years.

Yet while labelling such decisions as “historic” or “generational” make for good copy, they obscure the ultimate economic (and market) consequences. What might those be?

Let’s start with the facts. There are three pillars to the proposed reforms. First, defence spending above 1% of GDP would be exempt from fiscal rules – effectively removing a ceiling on borrowing to finance military expenditure. Second, a deficit-financed infrastructure fund worth €500bn (12% of GDP) would be created, with disbursements spread over a ten-year period. And finally, federal states would be allowed to run small deficits rather than being compelled to balance their budgets.

All of this is still subject to some wrangling to force it through a lame-duck session of the Bundestag, but most local political analysts expect it to pass. The nature of the proposed reforms makes it difficult to judge the likely size of the fiscal expansion, but we think it will be around 1-2% of GDP. If so, this would push the budget deficit to around 4.5% of GDP – levels that, aside periods of crisis such as the Covid pandemic, were last seen in the mid-1970s.

A positive development

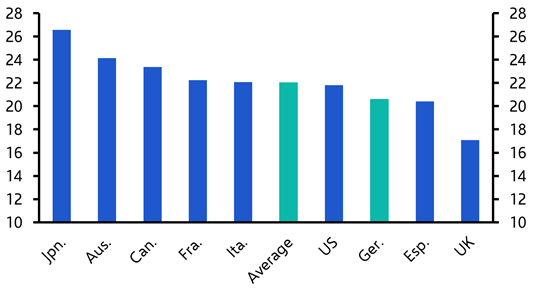

There are several reasons why this is good news. First, the scale of the reforms is large and focused on areas of strategic importance. The increase in defence spending has attracted most attention given recent events, but the poor state of Germany’s infrastructure has been a factor holding back growth in recent years. Germany suffers from one of the lowest investment rates among major economies but, unlike others such as the UK, this is not a function of a low saving rate. (See Chart 1.) Rather it reflects a reluctance to spend savings on investment. These reforms should start to change that.

|

Chart 1: Investment (% of GDP, 2024) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Analytics, Capital Economics. |

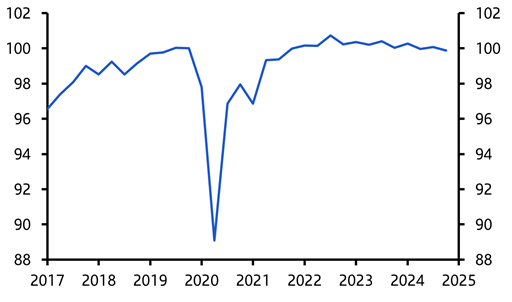

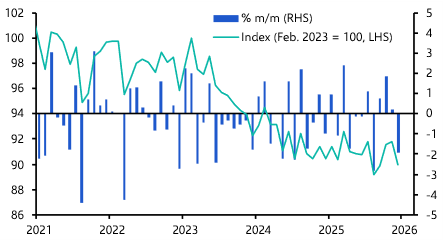

Second, to the extent that the additional expenditure on defence and infrastructure is directed towards domestic producers, it will boost demand in a German economy that has flat-lined for the past five years. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Germany Real GDP (Q4 2019 = 100) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Analytics, Capital Economics. |

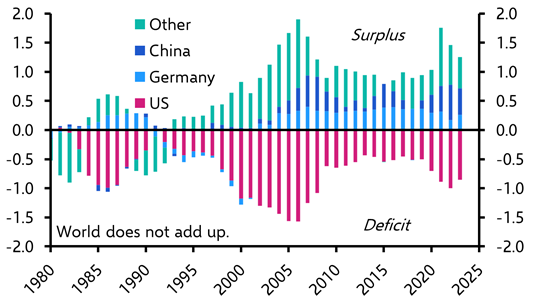

Third, if, by contrast, the additional spending is directed towards imports, it will export demand in other countries. Given the pattern of Germany’s trading relationships, economies in Europe are likely to benefit from any rise in German imports. But large suppliers of defence equipment, including the US and South Korea, may also benefit. Whatever happens, an increase in Germany’s budget deficit will (all other things being equal) reduce its current account surplus – thus helping to alleviate a key “surplus” component that has contributed to global (and regional) trade imbalances. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: Contributions to Global Current Account Imbalances (% of Global GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Analytics, Capital Economics. |

Finally, the proposed reforms in Germany may help to shift attitudes towards fiscal policy across Europe more generally. This is not to suggest that a widespread move towards fiscal profligacy would be welcome – on the contrary, it could be disastrous for some countries already struggling with large debts and deficits. But adapting fiscal rules to allow greater borrowing for investment and strategic priorities such as defence would be sensible.

Tempering some of the euphoria

All of this helps to explain the euphoria in regional stock markets – and the sharp sell-off in German bonds. Markets have taken the view that this is a game-changer for economic growth in both Germany and Europe. But some perspective is needed when thinking through what the economic consequences are likely to be in practice.

For a start, it will take time for the additional spending on both defence and infrastructure to take effect. The initial focus will be on identifying “shovel ready” projects, but these are notoriously difficult to find. Likewise, it will be difficult to increase defence spending rapidly. The order backlog at Rheinmetall RHM, Germany’s largest supplier to its defence industry, is currently equivalent to around three years of its annual turnover.

What’s more, the so-called “fiscal multiplier” for defence spending – which measures the bang for buck in terms of GDP – is typically quite low. While it varies according to how the money is spent (for example, whether it is on military personnel or equipment), most studies peg it at around 0.4-0.7 – in other words a 1 euro increase in defence spending leads to an increase in GDP of 40-70 cents.

The fact that Germany is currently operating at close to full employment adds to the reasons to think that the multiplier on additional government spending could be low. (The counterpart to this is that a large part of the recent weakness of Germany’s economy has been due to structural rather than cyclical factors.) The upshot is that we think that the boost to GDP growth may not come until 2026, and when it does the overall boost might be in the order of 0.5%-pts a year. That would be significant, but still only enough to raise the annual pace of growth to around 1%.

The wider impact

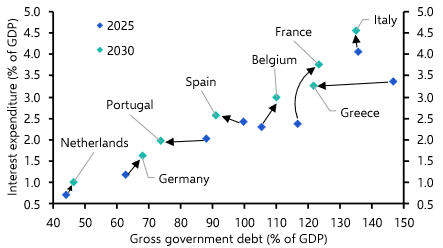

What about the consequences for the rest of Europe? One point to keep in mind is that, while Germany is important, it accounts for only one-third of euro-zone GDP. So a 0.5%-pts boost to GDP growth in Germany might boost euro-zone GDP growth by around 0.2%-pts. What’s more, while Germany’s shift may generate a permissive attitude towards fiscal policy in Europe – for example, the European Commission looks set to activate an “escape clause” in the EU’s budget rules to allow government to spend more on defence – the reality is that most countries have limited space to increase borrowing. Indeed, the embrace of looser fiscal policy in Germany could compound the challenges facing fiscally-constrained countries in the rest of the euro-zone since the rise in bund yields (i.e. the risk free rate in the euro-zone) is likely to push up borrowing costs everywhere but without the attendant benefits of higher economic growth. (Our interactive fiscal sustainability dashboard can be accessed here.)

One option would be to borrow more at an EU (rather than national) level in order to finance an increase in defence spending. Indeed, the European Commission proposed a “new EU instrument to provide Member States with loans backed by the EU budget of up to €150bn”. But this is only 1% of GDP which would probably be disbursed over several years and is a lot less than the €750bn of joint borrowing agreed for the pandemic recovery fund.

All of this creates something of a challenge for the ECB. There has been a fundamental shift in German fiscal policy, but the associated boost to economic growth may be a bit smaller than many expect, may take some time to arrive, and is unlikely to be replicated to the same extent across other euro-zone countries. We continue to think that inflation in the euro-zone will fall a bit further than policymakers expect this year and that growth will surprise on the downside. Accordingly, having cut interest rates to 2.5% last week, we think the ECB still has more work to do. But the fiscal shift in Germany means there is likely to be fewer rate cuts in this cycle that we had anticipated. As a result, we have revised up our end-2025 forecast for interest rates from 1.5% to 2.0%. And as the effects of fiscal support in Germany start to feed through, we think interest rates are likely to edge up in 2026 and 2027, perhaps reaching 3% or so.

In case you missed it:

Julian Evans-Pritchard unpacks the fiscal measures announced as part of last week’s NPC meeting in China – and finds there’s less to them than meets the eye.

Paul Ashworth pushes back on the idea that the US economy is heading into recession.

We have launched an interactive dashboard that allows clients to track developments in the trade war and download thousands of data points.