Also on the show, Paul Dales and Ruth Gregory from our UK team preview the coming week’s Spring Budget, including how far Jeremy Hunt might go to cut taxes but also why the country’s fiscal constraints mean that the winner of this year’s expected general election may face some ugly choices. (12:19-20:57)

Plus, as the European carbon price falls to fresh lows, Chief Commodities Economist Caroline Bain and David Oxley, our Climate Economics head, talk to David Wilder about the forces weighing on prices, but also why market reforms should see them turn around over the medium-term. (22:13-28:25)

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Thursday 29th February and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, our preview for the coming week's UK Spring Budget and why European carbon prices are likely to fall even further before rising to record highs. But first, Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist, joins me from the departure lounge of Hong Kong's Chek Lap Kok Airport to run through the week's big stories and look ahead to the coming five trading days. Hi there, Neil.

Neil Shearing

Hi, David. How are you?

David Wilder

Yeah, good. I know that you're boarding in a bit and there's a Twilight series to be binged. But before you fly, I thought we could run through some of the big themes that have come out of your meetings in Asia and the Middle East this past week. We ran through them just before recording. One thing that seems clear is that these were the ones that kept coming up. I mean, it's fair to say the global macro picture is relatively calm at the moment, certainly compared to first quarters gone by.

But these seem like identifiable, potential sources of market vol in coming weeks and months. First of all, unsurprisingly, China. That was one of the big questions, wasn't it? What's happening in the economy? A perennial question, I guess, because of what we've seen with the data, but also because government policy signals have been pretty murky. National People's Congress is starting this coming week. That's on Tuesday we'll get publication of growth and spending targets might give hints of what's going on, but not much more than that I suppose. So what is the big message here? What are you telling clients? Lots of gloom around about the outlook. Is it as bad as all that?

Neil Shearing

There is lots of gloom and I think that's perhaps the main message that I've taken from meetings over the past week in Asia. Lots of concern about the direction of the Chinese economy and lots of gloom about its current position. Actually, I think for once we're not quite as gloomy. If you look at our China Activity Proxy, which of course is our in-house measure of economic activity in China, that's actually suggesting that the economy has regained a bit of momentum over the past few months. And we suspect that momentum will continue to build over the first and second quarters of this year. This is, I think, primarily a response to fiscal support that was announced in August, September of last year and then stepped up towards the back end of 2023.

We started to see that feed through into government spending and that's then feeding through into activity. So actually, I don't think that the actual position of the Chinese economy right now is quite as bad as some of the gloomy headlines suggest. Where we have bigger concerns is over the longer-term outlook for the Chinese economy and in particular some of the structural challenges and issues it faces. The legacy of over-saving, the legacy of over-investment, problems in the property sector, greater state role in the allocation of resources, so on and so forth. Of course, we've talked about this lots before on this podcast. But right now, the economy is probably not quite as bad as some of the headlines suggest.

David Wilder

You just mentioned overinvestment and I want to get onto that longer term picture because another big political event in the coming week is Super Tuesday in the US, busiest day for state primaries and caucuses. I guess it would be surprising to say the least if Trump didn't trump them all. But on this idea of overinvestment in China, of overcapacity in China, we've talked last week on the podcast extensively about new trade war that could happen if Trump wins the election in November, if he makes good on those campaign promises to jack up tariffs on Chinese imports. But isn't it the case that in terms of trade action, regardless of who's in the White House come January 25, we're on a more dangerous path in terms of global willingness to absorb Chinese overcapacity, aren't we?

Neil Shearing

I think that's right. I think one of the things that has been missed in a lot of the debates, not just about Trump 2 .0 and what that would mean for the global economy, but for what's happening in China too at the moment, is that there has been an enormous investment in manufacturing capacity in China over the past couple of years since the pandemic. And what that's meant is that that industrial capacity, that manufacturing capacity has got to find a home. And that's being reflected in a large rebound in China's currency count surplus. Now, you won't necessarily see this in some of the official balance of payments data, but if you adjust that data to account for Chinese exports that go through bonded warehouses and offshore trade zones, then actually there's a substantial rebound in China's current account surplus as a share of global GDP. It's back to the peaks we saw around 2007, 2008 when measured as a share of global GDP. I think this sets the scene for a showdown between China and the rest of the world, no matter who's in the White House. The point is that China has this additional manufacturing capacity, it doesn't have the sources of domestic demand for that capacity so it's finding its way into overseas markets. That means that China will tend to run large surpluses and of course that will irk its trading partners. It means that whoever's in the White House and frankly in power in Europe, I think they're set on a collision course with Beijing over trade.

David Wilder

So when clients come to you in Asia, I know you've had loads of questions about this and the risks that lie ahead. What are you telling them in terms of how to play this?

Neil Shearing

I think one of the points to make from the start is that all of our forecasts assume no policy change. So we've not embedded any assumption about who wins the US election in November or indeed what policy after the election might be. We've assumed essentially that policy stays on its course. So we've not factored into our forecast at 10 % tariff imposed on all US imports, for example, which is what Trump's mooted on the campaign trail, nor have we factored into our forecast the threat of a 60 % tariff on all Chinese imports that Trump's made. Instead, we've thought about different scenarios and what those tariffs might mean. And actually, they're potentially quite substantial. In the first round of Trump tariffs during his first presidency, actually, the impact on both the US economy and for that matter, China's economy was not that great. That's partly because China let the renminbi fall and the move in the exchange rate did a large part of the work in terms of offsetting the effect of the tariffs. I think also frankly enforcement has been pretty weak, trades been routed through third party countries and so on and so forth. However, the scale and the scope of the measures that have been proposed are so much greater this time around. If they were to ever see the light of day with 60 % tariff on all Chinese imports, we estimate that the renminbi would have to fall to something like eight and a half against the dollar to fully offset the effects of that tariff. And I think the currency move on that scale will be politically difficult to stomach in Beijing. So, there's good reason to think that the effect of the tariffs and the trade action that's been proposed this time around, if it were to ever see the light of day, would have a more meaningful effect both on the US economy but also on the Chinese economy too.

David Wilder

What about all of this discussion about China as an exporter of deflation, just following on from what you were saying there about overcapacity? I mean, is there something to this? And if so, is that good news for advanced economies in terms of their fights to rein in inflation or is it just more fuel for a geopolitical backlash?

Neil Shearing

Yes, that's right. The counterpart to increased industrial manufacturing capacity in China has been that Chinese exporters have had to cut their prices in order to sell their goods. What we've seen is that although Chinese export volumes are currently running at a record high, export values have been under pressure. The nominal value of Chinese exports has fallen, but in volumes terms, Chinese exports have never been higher. Now, if you're a central banker in the West, that's good news. That helps in the fight against inflation. But I suspect on balance, it's not made a big contribution to the disinflation that we've seen across advanced economies over the past six months or so. And what's more, I think that the counterpart to this is, like I say, that it sets us up for a more fractious environment around trade over the next couple of years.

David Wilder

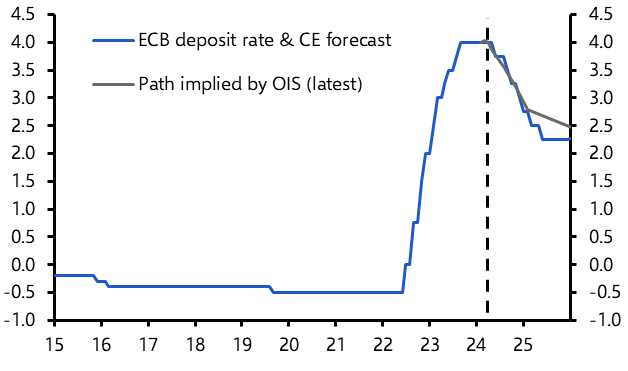

Let's stay on advanced economy inflation because one of the big policy events for the coming week is obviously the ECB meeting on Thursday, so a week out from this recording. It ties in with this other question that you kept getting from Dubai to Singapore. People want to know when inflation in Europe and the US for that matter is going to get back to target. What are you telling people?

Neil Shearing

I think one point to make from the start is that on several measures actually inflation may already be back at targets. One of the consequences of the way that we look at inflation, which is to say, look at the year on year changes in prices of the price today compared to the same month a year ago, is that when we see large changes in month to month prices, it often takes a while to feed through into those annual rates. Now, some of the annual rates are still quite elevated, but that reflects large monthly increases in prices around this time last year. If we look at the three month or three month annualized rates of inflation, particularly core inflation across Europe, across the US, they've fallen like a stone over the last six months or so, reflecting much smaller month -on -month increases in prices. And in fact, if you look at the UK, the Eurozone, the US, three -month or three -month annualized rates of core inflation are pretty much back to 2%. So in one sense, I think the answer to the question, when will inflation be back at 2 % or when will it be back at rates that central banks are comfortable with? Well, the answer is, it's probably already there. There's a question about whether that is sustainable or not. And I think on balance it probably is. But of course, the question for investors is what do central banks do about that? I think this is the critical issue. When you're thinking about monetary policy, you've got to get the real economy right. You've got to get the translation through to inflation right. And then you've got to get the reaction function of central banks right. And it's that part that I think is quite difficult at the moment. No central banker wants to be going down as history's next Arthur Burns. They want to be Paul Volcker in all of this and this means I think that they're just erring a bit more on the on the side of caution than they perhaps necessarily need to do. For that reason I suspect the ECB will probably delay rate cuts from April probably back to June to just to be on the on the cautious side but like I say I'm not entirely sure that's warranted.

David Wilder

Neil Shearing there about to board a flight in Hong Kong so excuse the occasional lapse in audio quality. On the ECB our preview of the meeting on Thursday will be on the podcast page. I'll also add our preview of the February US payrolls data that's coming on Friday. We're forecasting a still strong 250,000 rise in new jobs after January's blockbuster 353,000 increase. But the report also shows why there's good reasons to suspect that wage growth rose just 0.1 % month on month in February. The coming week will also be all over China's NPC. All our online and in -person events can be found on our website, capitaleconomics.com/events. And if you're a CE Advance subscriber, don't forget you get access to all our Drop-ins and all their underlying reports and data. That's CE Advance, our premium platform.

Now, another big political event in the coming week is the UK Spring Budget. That's on Wednesday when Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will stand up in the House of Commons and announce his latest fiscal plans. This is being billed as a Conservative party pitch to voters ahead of an expected general election this year and tax cuts are expected to be on the agenda. But how much cash can Mr Hunt splash and what's the bond market going to make of it all? Paul Dales, our Chief UK Economist, spoke with Deputy Chief UK Economist Ruth Gregory about what to expect this coming Wednesday, but also about the fiscal headaches that await the next government.

Here's that conversation now and it begins with Paul putting the coming week's budget statement in context.

Paul Dales

The budget is always couched as an event where the government makes sensible decisions about taxes and public spending. But on this occasion, we all know that it's really about trying to get as big a bang as possible in the opinion polls ahead of an election later this year. And of course, the incumbent government, the Conservatives are really trailing far behind in those polls at the moment. It seems widely expected that the Chancellor will probably try to get a bit of a boost by announcing some modest cuts to personal taxes, although his hands to some extent are tied by some fairly tight fiscal constraints. Now we've highlighted in detail the full analysis and what might happen in our UK Economics Focus preview in the budget. But Ruth, can you talk through to what extent any new policies announced in the budget are going to move the dial on the outlook for the UK economy and interest rates?

Ruth Gregory

Yeah, I think the short answer is probably that it won't move the dial very much. If the fiscal giveaway amounts to around £10bn in the 2024-25 financial year as we expect, and it's mostly made up of tax cuts, then it could boost the level of GDP a bit,

perhaps by around 0.2 % and that may help the economy emerge from recession around the middle of this year. It suggests the risks to our current GDP growth forecast of 0.2 % in 2024 maybe lie a bit to the upside. It might also support inflation a tiny bit. Yet I think all this talk of tax cuts, it does really ignore the heavily constrained fiscal backdrop to meet his fiscal rules, the Chancellor's banking on public spending plans that the next government may be unwilling or even unable to deliver. And that does mean that tax cuts in the budget will almost certainly be followed by a fiscal consolidation after the election. So I think any fiscal rush, fiscal sugar rush that we see this year, I don't think that will last and it probably won't prevent the Bank of England from cutting interest rates in the summer as we expect.

Paul Dales

I think that's a really great point. I mean, we know that there's an election coming, so it's not really about what this government announced. It's all about what the next government announces. After all, any policies announced now might just be reversed or overwritten by other policies come the autumn. And I guess in that sense, it means there's probably not going to be much of a reaction in the gilt market to anything announced in this budget. It really is a case of waiting to see what happens after the election. Now in that area, we have recently released some analysis that highlighted there aren't really major differences in policies between the current government and the opposition Labour party. And the similarities are actually what will probably set the tone for the economy after the election. And a lot of those relate to the fiscal constraints, which you've already touched upon. Ruth, can you sort of run through some of those fiscal constraints and what that might mean for the economy after the election.

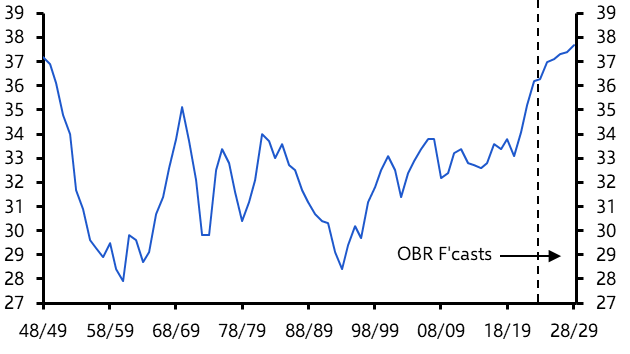

Ruth Gregory

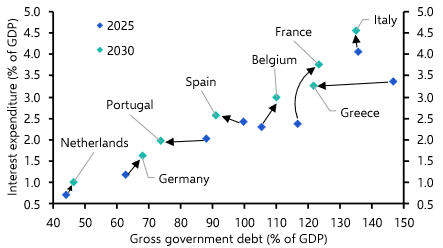

Yeah, as you say, these sort of overarching fiscal constraints, they are the same, aren't they, for both of the parties, the main parties. I guess we can group these fiscal constraints into two key categories. There's the forms of self-control and there's fiscal constraints which are being imposed on both the Conservative and the Labour parties. So with regards to the first category, the forms of self-control, I don't think either party is in a rush to repeat the mistake of 2022 when the adverse market reaction to the tax cutting bonanza in the mini budget brought the abrupt end to Liz Truss's tenure as prime minister. So both parties are preaching fiscal discipline. And then the second category is those fiscal constraints that are imposed on the parties. And here we're looking at the current climate of low GDP growth, higher interest rates. And that means that whoever wins the election will have to operate in a

situation where fiscal policy is much more restrictive in our analysis, we said, to the tune of around 1 % of GDP. And that's not all. The ageing population, that's increasing the upward pressure on health, social care and pension spending. We have geopolitical risks, which are putting upward pressure on defence spending. And all of this is happening as the pressure to deliver better public services is rising. So I think whatever the tax cut the Chancellor announces in this budget, as I said earlier, I do think a fiscal consolidation is almost certainly coming after the election. And perhaps whichever party wins the election will have quite a strong incentive to front load those tax rises as part of that fiscal consolidation, hoping there'll be a distant memory come the next election. So in terms of what, I guess, what that means for the economy, this probable fiscal squeeze in 2025, I think it does make us a bit more confident in our views that interest rates will end-2025 at 3%, which is lower than the current market pricing, which is at 4%.

Paul Dales

The way you listed all those challenges, it sounds like winning the next election is going to be a bit of a poison chalice for whoever is in government afterwards, as it is going to be a very challenging fiscal environment for them. I guess that's, you know, you said that there's a good chance that whoever wins will have to run a tighter ship when it comes to fiscal policy and acknowledge that government spending may have to be higher and that as a result, taxes will have to be higher. I suspect given that the bond market will probably reserve judgment really and wait to see until what policies are announced after the election. And our assumption is really that the government at the time will probably do enough to keep the bond market on side. But there are other scenarios out there. I mean, one could be that the government, the new government just

continues to kick the fiscal can down the road and almost ignores or denies the restraints that it is under. To what extent do you think the bond market would be forgiven in that situation?

Ruth Gregory

Well, I think I agree with what you've just said in that for now investors will probably continue to give the Chancellor the benefit of the doubt and wait to see what tax and spending policies are implemented after the election. But I think investors may balk if the winner does continue to ignore that fiscal reality. And as you say, if the government continues to project cuts in public spending or tax rises, it's got no intention of delivering. And I think investors may balk as well if the government loosens the fiscal rules so that any planned fiscal tightening is no longer required. And I think it's really important to put this in context with in the current environment, we have a very high debt to GDP ratio that's ratcheted up from 35 % prior to the global financial crisis to around 90 % last year. We have low GDP growth, higher interest rates. And I think all of this means that investors will be much more sensitive to any signs of fiscal profligacy over the next five years than they were over the last 15 years, for example.

Paul Dales

It's interesting to note, of course, the UK isn't the only country that has a high GDP growth rate. Many major economies are struggling with the same fiscal constraints caused by higher interest rates and reasonably low economic growth. The US of course has the benefit of being the US dollars, the biggest and most liquid treasury markets. There's always going to be an extra demand for their government bonds. But countries like Italy and France are also in a similar situation and the UK is one area of concern. I suppose if there's one thing that might help the UK is that the Liz Trust experience of 2022 is still fresh in the minds of UK policymakers. So whoever becomes the next government after the election, I think maybe that's one thing that will play on their minds and force them to acknowledge at least to a greater degree than perhaps the current government is the current fiscal constraints.

And in that sense, you're right, I think, Ruth, that what really is going to drive the UK government bond market over the next couple of years is the outlook for interest rates rather than fiscal concerns. And in that area, we do think that the big message is that interest rates in the UK may be cut further and faster than most people expect as the inflation problem disappears a bit quicker.

David Wilder

That was Paul Dales and Ruth Gregory on the UK Spring Budget. I'll post their preview of the budget on the podcast page and they'll be online on Wednesday shortly after Mr. Hunt's statement to take your questions, highlight key takeaways for the UK economy and housing market to discuss the market reactions, see how gilts are responding and where yields will go from here. That's three o 'clock in the afternoon London time, 10am New York on Wednesday. Details on the events page on site. Finally this week, what's behind the slump in the price of carbon traded on the European Union's Emissions Trading System and will it keep falling? This is a big question given that the ETS is meant to be an important driver of industrial decarbonisation, not just across the European economy, but from 2026 with a lot of companies that trade with those inside the block. To find out what's going on, I spoke with David Oxley, our Climate Economics Head, and with Caroline Bain, who's our Chief Commodities Economist.

They've just published in -depth insight into the ETS, including market mechanics, but also near to long -term carbon price forecasts. And I started with asking Caroline why, given the system was designed to increase the costs of polluting and encourage decarbonisation, prices have fallen by so much.

Caroline Bain

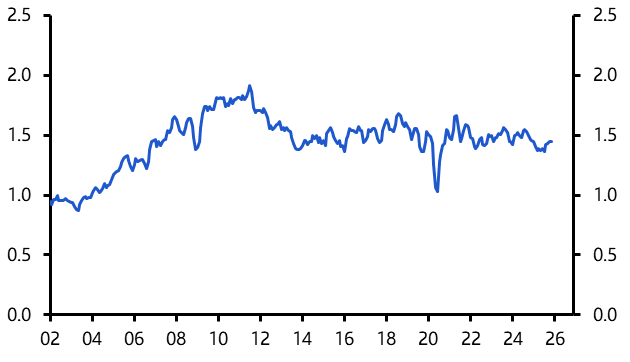

Yes, it does seem a bit counterintuitive. While our medium -term forecasts are driven by supply and demand fundamentals, in the near term, there can be much more market -based drivers.

One of the main catalysts for the drop in the carbon price has been the spectacular fall in natural gas prices over the last year or so. This has made gas more price competitive vis -a -vis coal and reduced Europe's coal use at the same time. As gas is about half as polluting as coal, it has in turn depressed demand for carbon permits and weighed on the price. At the same time, generally weak economic activity in Europe has been another factor reducing the demand for permits. In particular, heavy industry in Europe which cut back in the wake of the energy crisis has not recovered yet. So big falls in in carbon prices coming into this year.

David Wilder

What's the outlook for the rest of 2024 and into 2025? Do we need a view of energy prices there?

Caroline Bain

We suspect that carbon prices will start to recover over the course of this year and into next year as the ECB starts cutting interest rates, which will give a boost to economic activity and demand for permits.

We also think, as you just alluded to, that the big falls in gas prices are now behind us. However, the way that permit issuance goes, there's going to be more available this year and next than in subsequent years, which will ultimately act as a bit of a ceiling on prices in the near term. So putting all this together, we think prices will trough somewhere close to 40 euros per tonne in the middle of this year before starting to recover gradually over the next 18 months and to end next year closer to 65 euros.

David Wilder

David, let's turn to you. Let's look longer term. Tell us what CBAM is and how it could shake up the market for carbon permits.

David Oxley

So CBAM is a snazzy acronym that stands for Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which is essentially a tax on emissions that are embedded in imports coming into the EU.

This is designed to reduce what's known as carbon leakage, just emissions being outsourced really. So you might stop producing steel in Europe, but that doesn't stop the emissions related to the steel you consume if you're just importing steel from, say, China, where those emissions would actually be counted. The CBAM is currently in a phony war stage where there's just reporting standards being built up. It's going to come in into action in 2026 and be phased in gradually over the next seven years or so. It's worth saying that the CBAM itself will have no direct impacts on the market for carbon permits themselves. So in practice, although the price of the import licenses that importers will need to buy will be linked to the price of carbon permits, they won't actually, these importers be buying carbon permits themselves. However, to the extent that the imposition of the CBAM causes funds based in the EU to change their decarbonisation plans, it will have indirect knock-on impacts on the demand for EU carbon permits.

David Wilder

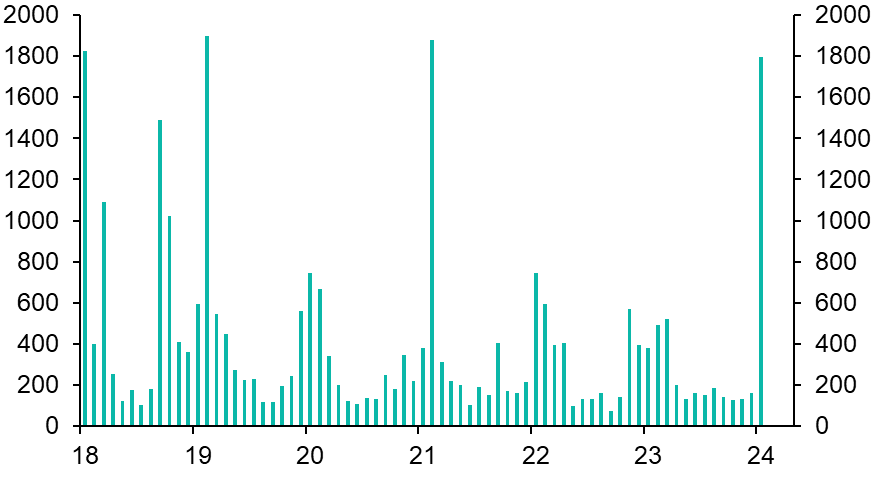

Can you talk a bit about the supply side, the mechanics of the market and this idea that over time the supply of permits is going to be reduced in order to try to incentivise decarbonisation by industry? What does that all mean for the longer -term price outlook?

David Oxley

Yes, well the ETS had lots of teething problems in its formative and early teenage years which were principally related to the oversupply of permits during the second phase between 2008 and 2012 and the related overhang of permit supply that persisted in the system through most of the 2010s. This kept the cost of polluting the cost of a permit at rock bottom levels and really undercut the economic incentives for firms to reduce emissions. Crucially, what we've seen over the last five or six years is that reforms to the system have started to address many of these shortcomings. So we now have a strong mechanism in place that's designed to reduce the overhang of supply in the market. And also, the pace at which the EU is going to reduce the supply of emissions each year, what's known as the emissions cap, is really going to become quite aggressive between now and 2030. So the combination of, on the supply side, some of these things have really been addressed. As to what this means for prices, that all depends on what happens to demand. Our base case is that demand for permits is not going to fall as quickly as supply, which should push the price of a permit up over time. Our baseline forecast is the price of a permit going from around 50 euros per tonne at present to close to 150 euros per tonne by 2030.

David Wilder

The ETS, it's 20 years old next year. Just taking a step back, is this a viable mechanism for getting industry to reduce emissions?

David Oxley

Well, I think now that these structural shortcomings that really dogged the system for many years have been addressed, I think the answer is yes. To be clear, how much of an incentive a rise in carbon price will put on firms to reduce emissions will depend from firm to firm and from installation to installation. But clearly, I mean, our forecast that's consistent with a carbon price well in excess of 100 euros per tonne in the late 2020s was going to impose a much greater economic incentive on firms to reduce emissions than it would have done if it had continued on 10, 20, 30 euros per tonne. So I think in that sense, the reforms that the EU have made, they've learned by doing. It took a long time to get there, but I think this is now a viable system. And crucially, I think they've done a lot of the hard yards of learning how to put carbon and systems in place. So I think it really is a system that others can look and learn from.

David Wilder

That's it for this week. We'll be back next week to unpack that ECB decision, talk more about global growth, talk more on geoeconomics, including a preview of Russia's election. The outcome may not be a nail -biter, but there's much to be said about the outlook for Vladimir Putin's war economy. Until then, goodbye.