Donald Trump’s sweeping election victory has prompted a scramble among economic forecasters to adjust their numbers in anticipation of a very different path for US policy.

We’re not convinced that the near-term macroeconomic impact of Trump’s return to the White House will be quite as large as many now seem to believe, particularly outside of the US. This is not to say that his re-election is unimportant for the world economy – more that its consequences are likely to be reflected in much more than immediate changes to global GDP and inflation.

More inflation for the US

For the US economy, a consensus is now forming that Trump’s re-election will result in stronger GDP growth fuelled by lower taxes and fiscal expansion. We’re not so sure. If nothing else, the absence of a filibuster-proof majority in Congress will make it harder for Trump to pass a very large package of tax cuts. More fundamentally, the US economy is now in a very different place to where it was during his first administration in 2016. The federal budget deficit is larger and the government debt burden is higher, meaning a major fiscal expansion would risk a strong backlash in the bond market. What’s more, even if Trump pressed on regardless, with the economy at close to full employment this would be more likely to generate faster inflation than it would higher output.

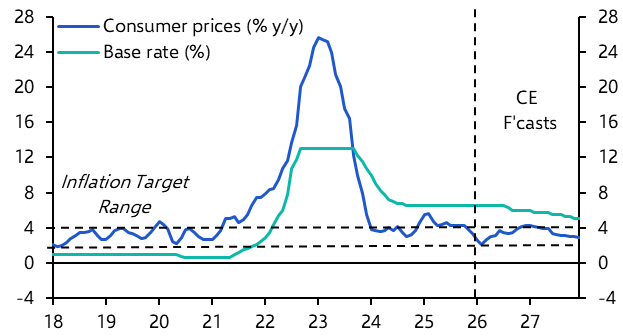

Indeed, while there remains enormous uncertainty about the policies that a Trump administration would enact (as well as when they might take effect), the common thread running through the president-elect’s campaign pledges is that they would be inflationary. Curbs on immigration, substantially higher tariffs and tax cuts (if they materialise) would all stoke price pressures. Accordingly, we are minded to add around 1% to our US inflation forecast between mid-2025 and mid-2026. We have also revised up our forecast for US interest rates by 50bps, and now anticipate that they will trough at 3.50-3.75% in this cycle. That means we now expect higher US government bond yields and a stronger dollar.

Mexico and China in the firing line…

Internationally, the immediate focus has been on Trump’s plans to levy substantial tariffs on US imports. We expect these to be introduced some time in the second quarter next year via executive action, though it remains to be seen how much of what was pledged on the campaign trail is a negotiating tactic and how much becomes policy. If the tariff levels that Trump has bandied around are more than a ploy, then Mexico’s economy is looking particularly vulnerable. Even if Mexican public finances weren’t already so strained, a strong dollar would limit the ability of its policymakers to counter the effect of tariffs with fiscal or monetary support. As a result, it’s possible that US tariffs could shave 0.5% off Mexico’s GDP in 2025-26. China is also in the firing line, but has more capacity to offset the hit from tariffs and will prove more economically resilient than most anticipate.

…but global trade likely to hold up

The impact of potential tariffs elsewhere in the world, including in Europe, is also likely to be smaller than many now seem to fear. The greatest risk is that the imposition of tariffs by the US leads to tit-for-tat responses by governments in other major economies that tip the world into a global trade war. The effects of this would be devastating, but for now this would be best characterised as a ‘low probability-high impact’ event. As things stand, we still find it more likely that world trade growth will recover next year as the effects of monetary policy loosening feed through.

Why Trump really matters

For most of the rest of the world, the impact of a second Trump administration will extend far beyond any impact on short-term macro variables such as changes in GDP.

From Brussels to Tokyo and Taipei to Kyiv, governments worldwide are now scrambling to prepare for a more isolationist US administration led by a president who sees diplomacy in nakedly transactional terms. Those countries that have traditionally enjoyed close alignment with the US may not see any major near-term macro impact from Trump’s return, but it will have significant, longer-term economic and national security consequences.

The challenges are that much greater in a world economic system being reshaped by the fracturing of the US-China relationship – a multi-year process that Trump did so much to accelerate during this first term in office. The nature of this fracturing process is likely to change as Trump places greater emphasis on the use of tariffs to define the contours of trade with China, rather than the export controls that the Biden administration has leant on.

Most of all, Trump’s return will lead to a more uncertain global policymaking environment. This is important because this election has not happened in a vacuum. This past week also saw the collapse of Germany’s government, threatening political paralysis in Europe’s most important economy just as US support for Ukraine comes into fundamental question. On the other hand, German elections next year could also produce a leader more willing to talk tough on China, and with whom Trump may be able to find some common ground.

A shift in Germany’s attitude towards China is just one of the myriad ways in which his return to power could influence the global economic order. Those changes are likely to be profound, but they won’t be captured by the regular churn of data releases due in the coming weeks and months.

Further reading

All of our key analysis about what Trump’s return means for macro and markets can be found on this dedicated page.

Mark Williams explains why another hotly anticipated Chinese government announcement fell short of market expectations for major stimulus.

As the latest UN Climate Conference, or COP, begins in Baku, Hamad Hussain shows why efforts to reach multilateral agreement such as these are increasingly unlikely in a fracturing world – and even more so with Donald Trump’s return.