- Could inflation rebound?

- Could escalation in the Middle East drive up inflation?

- Are falling commercial real estate valuations fuelling a new banking crisis?

- Is the boom in US productivity growth sustainable?

- Will Donald Trump start a trade war if he’s re-elected?

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 9th February and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder, coming up, the outlook for the dollar and the latest on EM policy and Frontier Market Default Risk. But first, Neil Shearing, our Group Chief Economist, joins me once again to poke through the embers of another busy week in macro markets and preview the week ahead. Hi Neil.

Neil Shearing

Hi David.

David Wilder

Let's start with something different this week. I thought we could address the most commonly asked client questions we've had over the past five days.

Now, these have come in via our regular online briefings, but also via the Q&A function on CE Advance as our premium platform, as well as old school email. I was going to pitch this as a quickfire round, but my sense is that some of these might take a bit more time to address. So let's kick off. First question, will inflation rebound? This was asked several times during our central bank drop-in, which is one of our short form online briefings last week. Are we underestimating the risk of a bounce back?

Neil Shearing

Yes, and not just on the Drop-In. I think this is the question that we've been asked more than any other over the past couple of weeks. I think it perhaps reflects the fact that central bankers themselves have become a bit spooked by the tightness of labour markets. My take on this is when we think about whether inflation might rebound over the next quarter or so, we should factors that could push up inflation that are frankly very difficult to anticipate. So the most obvious would be war in the Middle East and the impact on energy prices that could have. We could get bad weather, bad harvests. There's a whole manner of shocks that could cause supply disruption and the push up prices. The second way in which inflation could rise is economic influences. Most of the concern here, like I said at the start, I think is about the tiniest of labour markets. Obviously that blockbuster.

January payrolls report from the US has ruffled a few feathers. Now, our sense here remains that if you look at other measures of labour market strength, they continue to suggest that labour markets are becoming a bit less tight. So, quick rates have gone down, vacancy rates have gone down, hiring intentions have cooled too. And if we look at some of the forward-looking indicators, that continues to point to stowaways growth. Obviously, that's what really matters for inflation. Yes, there's a lot of ways in which you can envisage inflation increasing, but they're mainly through kind of non-economic shocks. On the economic side, I'm pretty confident that inflation is going to trend lower over the next quarter or so. Incidentally, we're going to get a slew of inflation data over the next week, particularly from the UK. That might actually show an uptick in inflation in the UK for January, but that's mainly about base effects.

David Wilder

You mentioned just there the war in the Middle East as a risk to inflation. Here's an associated question which we've been asked countless times by clients, particularly during our geopolitics and shipping disruption drop-in which we held on Wednesday. And the question was whether conflict in the Middle East could escalate to the point that it leads to a rise in inflation.

Neil Shearing

Yes, I think we might get onto this when we talk about inflation. A couple of points I think are worth making here. The first is that we have seen obviously a sharp increase in spot rates for shipping. But actually, those take a long time to pass through into total shipping costs due to the way that shipping contracts are structured over long periods. So that sharp increase in spot rates will not necessarily translate into an immediate and comparable increase in shipping costs. And what's more, shipping costs are only a small proportion of total costs that importers face. So that doesn't pose, I think, at this stage, a substantial inflationary threat.

Now, the rejoinder to this that's normally pointed out by clients at this point is that if you look at the business surveys, the prices paid balances by firms has started to pick up over the past couple of months. And that's certainly true. But then if you plot that against total core goods inflation in advanced economies, it's still consistent with total core goods inflation being essentially zero. So yes, the prices paid balances have started to pick back up a bit, but that's mainly because they cratered last year. So I think you can construct a case that if shipping costs remain very high and tensions in the Middle East continue to escalate, then that becomes a bit more of an inflationary concern. But to really deliver sharp increases in inflation, our view remains that you need that these translate into actual disruption to energy supplies and a sharp rise in oil prices. And at the moment, oil is up a bit this week, it's back at $80 a barrel, but we're not seeing those big surges in oil prices that would pose a really substantial inflationary threat.

David Wilder

Okay. This is perhaps the most asked question over the past few days, actually the week before as well, all around commercial real estate exposure. Some of these questions are coming from clients as part of their registration for this Drop-in that we're holding on distress in real estate in US, UK and Europe, which is this coming Wednesday. The questions are all of the same theme. Is this another banking crisis or a continuation even of last year's and how do you think it could affect central bank thinking?

Neil Shearing

Well, in the first point I would make is that distress in real estate markets, commercial real estate markets, and particularly in office markets, has further to run. It's going to deepen further over the coming months and quarters. That's particularly true, as I say, of office markets. And what that means is that as we start to see delinquencies on bank loans to commercial real estate, particularly office markets, pick up. Lenders are going to start to come under pressure. We've already seen delinquencies on commercial mortgage backed securities increase in this sector. It's taken a bit longer to feed through into bank loans, but I think that's coming down the track. So if you want to kind of estimate, our view is that about $60 billion worth of loan losses in the US on commercial real estate loans from banks are likely over the next year or so. So $60 billion of loan losses in the US on the commercial real estate loans, that's gonna cause problems for some lenders. However, take a step back and compare that to the total size of the US financial system, and it's small in the grand scheme of things. So that's $60 billion of loan losses on commercial real estate loans compares to total equity capital in the US bank system of over $2 trillion. So I think both things can kind of be true here. One is that there's more distress coming, particularly office markets, and that banks are going to face further losses on loans to that sector. On the other hand, I don't believe at this stage it poses a systemic threat to the US banking system or indeed the global banking system. Banks are provisioned for those losses in many cases, capital buffers are large, and actually we had the senior loan officer survey from the US last week that actually suggested that the worst of the credit crunch in the wider US economy might now be easing.

So problems to deepen in the office market in particular, but I don't think at this stage it poses a systemic risk to the US financial system or the broader global banking system.

David Wilder

But presumably more isolated flare-ups like New York Community.

Neil Shearing

Absolutely. We should expect more of those types of events going forward.

David Wilder

Okay. Let's move on. Lots of questions have come in about this over the past few weeks actually, but we had one this last week on the Q&A function of Advance. It's around those US productivity growth numbers. You spoke last week on this issue in terms of the impact of AI on productivity in the US. You downplayed the likelihood that AI is having an effect at the moment, but we do have a client asking what did drive those bumper productivity numbers last year and is it sustainable?

Neil Shearing

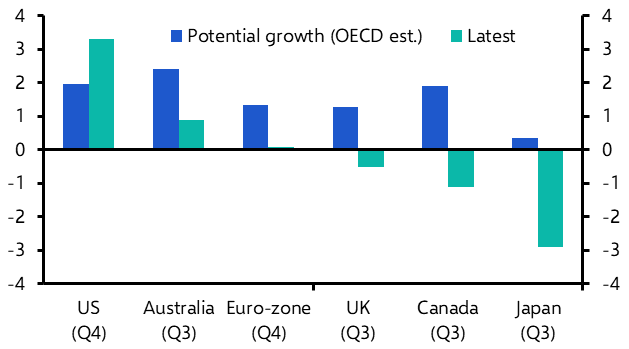

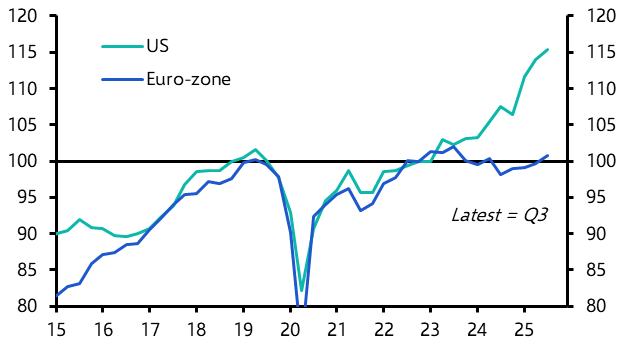

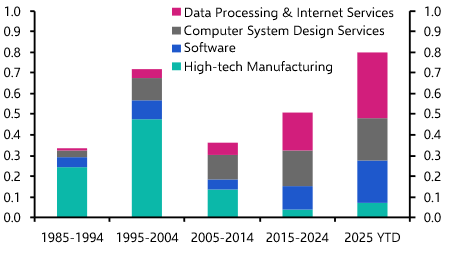

Well, the first point on whether or not those bumper productivity numbers are sustainable, I think unfortunately the short answer is no. Productivity in the US expanded at a 4% annualised in the second half of 2023. I don't think anyone thinks that trend productivity growth in the US is going to get close to 4% over the next decade, even if you're extremely bullish. I don't think that 4% number is sustainable. Begs the question, what's driving it and what might be a kind of trend productivity growth number in the US. Now, one theory is you're right, this could be the early signs of benefits from AI. I think that, like I said last week, is a bit of a stretch. It's more likely in our view, and we wrote about this week, is that the upturn in productivity growth is predominantly a cyclical response to rising capacity utilisation, particularly in the labour market. In other words, it's a product of the fact that demand has been strong relative to supply, particularly supply of workers, and that's forced firms to find other ways of increasing output, for example, by investing in automation, increasing the efficiency of their existing workforce and so on and so forth. Hence,

run the economy a bit hot relative to supply, you get a pickup in productivity growth. And I think that's what we've seen in the US over the past six months or so. Really interesting that we've not seen that type of phenomenon in Europe. So it's predominantly a US phenomenon and I think it's predominantly a product of the fact that the US economy has been allowed to run hot, particularly relative to labor supply. Looking ahead, I think we should expect productivity growth to stabilize at the kind of 1.5-2% range. Now, interestingly, the key point there is that if you look at the forward looking indicators of wage growth, that's suggesting that wage growth in the US might slow to a 3-3.5% range over the next six months or so. If you've got trend productivity growth of 1.5-2%, that's perfectly consistent with a 2% inflation target. In fact, it might even be consistent with undershooting that 2% inflation target. So the big question for the Fed over the next year or so is not necessarily going to be what happens to inflation, which obviously we're all focusing on. It's what's going to happen to productivity and in turn what that means for inflation. So if we're going to focus on one data series over the next 12, 18 months that we've not paid much attention to over the past 12 months or so, I think it should be these productivity numbers.

David Wilder

And last question in our inaugural quickfire round. It's about Trump. Growing number of questions coming into the economist team. I suspect we're getting lots, lots more on this in the coming months. Specific question from a client, if Donald Trump wins the presidential election in November, will that mark the start of a new global trade war? And if so, which economies are most vulnerable?

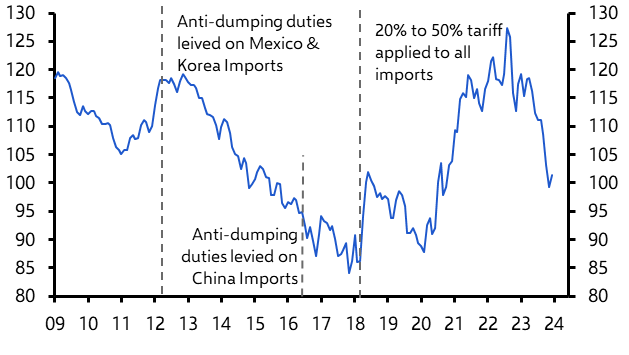

Neil Shearing

Yeah, great question. Big question and difficult to answer in a short space of time. But I think two points are important to consider. The first is the scope of any measures, be they trade tariffs or any other restrictions on trade. Are they focused principally on China or do they go much wider and affect other countries? And then the second is how do those countries respond? Do they retaliate to any measures imposed upon them? Now, one scenario that Trump's talks about on the campaign trail has been a 60% tariff on all Chinese imports. Now, if that was the extent of the measures, it would have a pretty wrenching effect on US-China trade. We might see trade routed through third party countries. And I think it would accelerate the splintering of global supply chains into US and China aligned blocks. And this is the work that we've been doing on global fracturing that we've talked about on this podcast before. So a tariff imposed just on China, particularly at those punitive levels, would accelerate that fracturing of the global economy and global supply chains and benefit economies like Vietnam and Mexico, and perhaps even India that have been beneficiaries of fracturing so far. The second scenario, which I think is in some ways even more troubling, is that the US becomes more isolationist. It turns in on itself. One example of this would be if Trump pursued the idea of a 10% unilateral tariff on all imports that he's talked about on the campaign trail. That would include imports not just from China, but from Europe, from India, from Mexico, from a whole host of countries. Now, I suspect in practice there would be exemptions and car fires for more friendly countries. But were that to materialize, it would almost certainly provoke retaliation from the likes of say European nations if they were to find themselves under fire. And of course, there's other ways that this could play out too, for example, more Germany retreating from WTO, more pressure on NATO and the impact that could have on the US relationship with Europe. So all of these impose economic costs, not just on the US but on its trading partners. No one is better off as a result of trade restrictions. But I think the extent of those costs, the scale of those costs depends on the scope of the measures and the retaliation by trading partners.

David Wilder

Neil Shearing there and our attempt at a quickfire question round. He covered a lot of territory in that short time. Obviously, we've got much more in-depth analysis on all of those issues that we've talked about, from the Middle East to US productivity to Trump tariff threats. It's all on our website, capital economics.com for unhindered access to all our coverage that includes prop data and interactive dashboards, but also to engage directly with the economist team and ask your specific questions. You'll want CE Advance - details about that on capitaleconomics.com/ce-advance.

Watch out for our coverage of those CPI releases that Neil mentioned. That includes a Drop-in shortly after the US release on Tuesday, in which our US team is going to be taking questions and talking disinflation, Fed policy, but also their work on what's happening with US productivity. For more on real estate, check out our drop in on Wednesday. That's going to be looking at distress across the US, European and UK markets. If you want to know how bad it's going to get, register for that session and get your questions to our property team. We've got a page dedicated to this painful adjustment in CRE and I'll put that on the podcast page. And we've got another drop in next week on Tuesday, all about Indonesia's presidential election. We're forecasting that Indonesia will become the world's fifth biggest economy by 2050. But this election outcome could be a downside risk to that view. Register to find out why, read our election preview report. Again, I'll post that on the page.

Now, a combination of strong data and Fed pushback on rates have boosted the US dollar this year, but is the strength sustainable? To find out, I spoke to Jonathan Petersen from our FX team about the dollar outlook, including the impact of AI hype and our framework for understanding how changes in the global economy affect its relative value. Here's that conversation now, and it begins with Jonathan explaining how the dollar has performed so far in 2024.

Jonathan Petersen

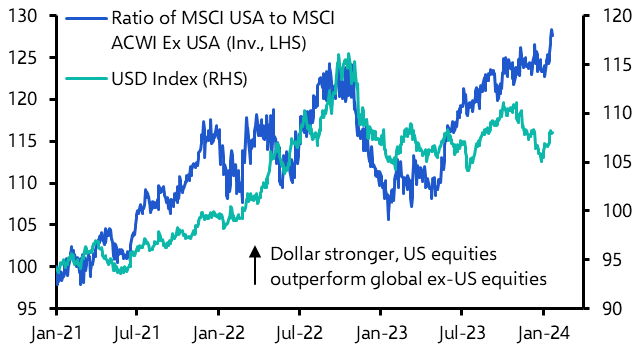

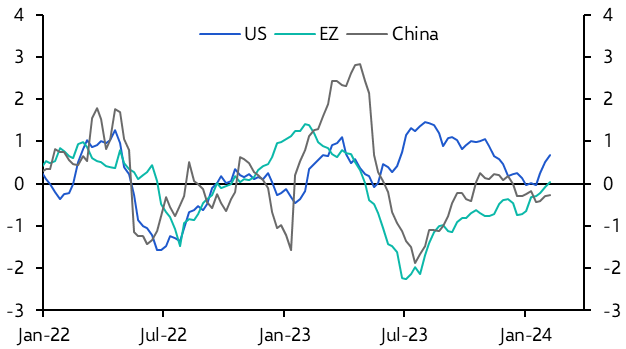

So after a very sharp fall in Q4 of last year, the dollar's definitely started 2024 on the front foot. The DXY Index, which is probably the most common measure of the dollar, has risen about 3% to 4% this year, its highest level in about three months. So a lot of it looks like it's just sort of reversed to the moves that we saw in Q4 in last year. And there's been a variety of drivers behind this. This has coincided with exceptional strength in US equities, which have outperformed equity markets elsewhere. And also, bond yields in the US rising more so than elsewhere, helped by the fact that the Fed has continued to maintain a little bit more of a hawkish stance than might have been anticipated at its meeting in January. And so taken together, I think the underlying theme here that's led to this strong start for the dollar really has to do with US economic outperformance, especially when we consider relative to elsewhere and some of the pessimism we've seen around the outlook in Europe, China, and other major economies around the world.

David Wilder

Your analysis references something called the "dollar smile" framework. It's an intriguing name. Tell us what it is and how it helps us think about where the dollar is going.

Jonathan Petersen

Absolutely. So the "dollar smile" framework is one that we refer to pretty regularly and it's definitely come in handy over the past couple of years as we've seen a lot of the ups and downs, not just with the energy shock we saw in 2022, but then the reversion last year. And it's really something that helps us think about where exactly are we in the dollar cycle. When it comes to is this a dollar positive or a dollar negative environment. So it's probably best to just start with defining what the dollar smile is. A bit of a strange name as you said and really it's called the smile because it talks about three different scenarios and the sort of left-hand side of the smile and the right-hand side of the smile sort of both points to appreciation whereas the middle is talking about dollar depreciation. And so it's really relating to those three scenarios. In short, the dollar tends to appreciate in two circumstances. First there's what's referred to as sort of the left-hand side of the smile. And that's when global growth is slowing down or we're in a global recession. That sort of risk-off dynamic bids up the dollar because of safe haven demand. And that's all tied together with the US dollar status as reserve currency. We go to the right-hand side of the smile. And when the global economy is sort of at normal times and expanding and things are sort of humming along. It's really the relative performance that matters. It matters, is the US economy at the head of the pack when it comes to the global economy or is it lagging? As you could probably guess, this is something that coming out of the pandemic with the massive fiscal stimulus, one of the key themes that's been constant throughout the past couple of years has been US economic outperformance. That's very much continued. We tend to see when the US economy is outperforming monetary policy might be tighter. That translates into higher bond yields. That's a draw for international capital. Similarly, we see US equities perhaps outperforming because the US economy is doing well. The prospects for earnings in those companies are doing well. Maybe risk appetite is particularly strong in the US. That draws capital into the US as well and pushes up the dollar. So that's sort of the broad mechanism. And again, when times are very bad, it's good for the dollar. When times are good, and the US economy is outperforming, that's also very good for the dollar. Where we get to the middle, which is sometimes where we find ourselves, is when we're in times of expansion but other economies, let's say China or Europe, are leading the charge. And that tends to be associated or coincide with a weakening dollar.

Jonathan Petersen

So talk about that framework in the context of Fed policy. We still have some fairly aggressive cuts in our forecast this year, despite recent pushback from officials. How does that sit against what's happening with rates in the rest of the world? What does that ultimately mean for the dollar outlook? Yeah. So going into this year, one of the reasons why we didn't have major moves in the dollar was because we largely agreed with what was being discounted in markets around gradual rate cuts around the first or second quarter of this year in not just the US, but most major economies. And this recent data has been one of the factors that's certainly changed the thinking around that.

With the Fed very much having a data dependent sort of mindset, if the data is coming in stronger than expected, all things equal, it's going to push up rate expectations and lead to higher bond yields, which again, typically associated with the US, so long as, as you pointed out, they're rising faster in the US than elsewhere. So how the Fed responds to this is ultimately going to be the deciding factor about how long the dollar stays strong. Because whether or not we continue to get upside surprises in the data is certainly one part of the equation. The other part of course is the reaction function. Our personal sense, as you mentioned when it comes to our own forecast, which is for six rate cuts this year, double that of what the Fed is projecting, which is three rate cuts this year. Our sense is that even if we do get stronger economic performance out of the US over the next couple of months, that really doesn't change the bigger picture. The bigger picture is that we have lots of different components, underlying components of inflation that do look at to weaken throughout the remainder of this year. And really we think even if there's just a moderate loosening of the labor market, we don't get outright falls in employment or rise in the unemployment rate. We think the Fed is main focus is still going to be on that falling disinflation and that's going to be what enables them to follow through with rate cuts. So on the one hand, we have this short-term continued economic resilience in the US that we don't necessarily expect to last much longer. And later down the line, we do see the Fed eventually easing rates. So meanwhile, there's a US equity bubble going on that's at least in the last major equity bubble we saw in the late 90s, pointed to a stronger dollar. So when we put all of this together, what does it actually mean for the dollar? And of course, when you measure the dollar, it really depends on against which currencies. I think the big picture is really that we expect a relatively flat outlook for the dollar in aggregate this year, if you were to measure it on average. We think in the short term, the risks are certainly to the upside, given everything we had talked about with potential for Fed cuts being delayed and the potential for US economic resilience continuing to draw enthusiasm towards US markets to the benefit of the US dollar. But eventually later this year, we think ultimately the shift in bond yields and the Fed moving forward with its policy easing is going to be what brings the dollar back towards where it started the year. So we're not talking about massive moves here one direction or another. To the upside, we don't expect it to exceed the cyclical highs that we've seen over the past couple of years. But at the same time, to the downside, it does have some of these tailwinds, so we're not expecting a massive move. We do have a bit of a mixed outlook across G10, and so I would encourage listeners to look into sort of the currency-specific outlooks that we have really do think there's a lot of different cross currents here and this is where digging into the details really matters.

David Wilder

You touched on capital inflows earlier. Talk a little bit about the dollar in the context of what we're seeing with US equities and this hype around AI specifically. Is that supportive of the greenback longer term?

Jonathan Petersen

So I think the dollar smile framework actually works quite well here as well, because typically people associate risk on with a weaker dollar risk off with a stronger dollar. And that risk-off and strengthening dollar definitely holds true in most circumstances. Again, talking about that safe haven demand. When it comes to when equity markets, global equity markets are generally rising, it again goes back to being a relative story. And while it's not perfect, it's not going to match up on a day-to-day basis. The performance of the US relative to other equity markets tends to broadly mirror the performane in the dollar over a sort of multi-month or even multi-year period. So it's definitely a factor that comes into our analysis as we're looking at our outlook for the dollar against other currencies. And so far this year, that's definitely been a tailwind for the dollar. When we look ahead, there's a few things that make us a little bit more skeptical that we're going to have a repeat of the dollar rally of the late 90s, even though we do think we are going to have a repeat of the equity bubble of the dot com era. And it really has to do with the starting point. Ultimately, we think that there's been quite a substantial amount of capital inflows already into the US, and we don't see scope for that to expand much further. And the second point I would mention is valuation. We're starting with the dollar at a relatively strong valuation. It's not overvalued by our measures, but compared to where it began its rally in the mid 1990s, there just isn't as much scope for it to strengthen. Our bullish view on equities for the remainder of this year and next year, even though it has been a tailwind, or at least it's coincided with dollar strength since the outset of this year. We wouldn't be surprised if we ended up with a US equity bubble, but the dollar not necessarily breaching new cyclical highs as part of that process.

David Wilder

I can't let you go without asking about sterling. We've got a UK CPI releases coming Wednesday. Seems like a good opportunity to ask about our sterling forecast. Pretty bearish one, isn't it?

Jonathan Petersen

That's right. And that's contrary to the sort of year-to-date performance that we've seen. Other than the dollar, sterling is the best performing G10 currency. So it's remained resilient and it is one of our key calls, so to speak. And our bearish view on sterling really has to do with a few factors. The first and probably the primary most important factor has to do with our view on Bank of England. And like the US, our view is founded ultimately on our view that inflation in the UK is going to fall faster and to a lower point generally than widely anticipated at this stage, certainly below what the Bank of England is currently projecting. And when we look at where our forecasts are for the Bank of England's policy rate relative to those in the market, we see quite a gap there. So I mentioned earlier that we didn't expect huge swings in yields to really be drivers of the currency markets this year. Sterling is definitely one of those exceptions. We do think guilt yields are going to fall relative to treasury yields. And that is ultimately the channel that we think is going to lead to sterling weakness. From where we are right now, it's a little bit more of a punchy forecast than our other G10 currency forecast. We see it falling from about 1.26, the GDPUSD rate, to 120 by the end of the year. And I think the reason for this is it's not just this yield gap, right? That's part of the equation, but we think that the other important factor here really has to do with valuation. Because it's been resilient not just over the past couple of months, but indeed over the past six to 12 months as the Bank of England has been among the more hawkish central banks, that resilience has ultimately led to it being relatively highly valued on a trade weighted inflation adjusted basis, which is one of the measures we look at for valuation. And all that is to say it certainly has the most scope to fall when we look at European currencies. And so even though it's not a major catalyst in terms of the size of the move we expect in gilt yields relative to treasury yields, we think even that small catalyst might have an outsized response because of sterling's high valuation.

David Wilder

Jonathan Peterson there on the dollar's performance and on sterling ahead of the coming week's CPI release. His analysis about the dollar, including that smile framework he discussed, will be on the podcast page. I want to leave you this week with a clip from our drop in held last Thursday, all about emerging markets. This is a session that the team hold in the first week of each month where they take questions from across our client base. So EM portfolio managers, we've got some country risk analysts, some non-financial corporates are in there too. In this clip, which has been edited for clarity, you're going to hear Shilan Shah, our deputy chief EM economist, talking to economists Leah Fahy, Gareth Leather and David Omajomolo. It starts with Leah talking about how EM policymakers have behaved following that last Fed meeting pushing back on talk of a near term rate cut.

Leah Fahy

Yeah, so I guess there hasn't really been a one size fits all reaction to the Fed from EMs, but in general, they seem to have kind of stuck to the course that we expected prior to the Fed's meeting. So it didn't really stop central banks in Latin America from cutting rates. We had Chile and Brazil, both lower rates, following the Fed meeting on Wednesday. And we also had Colombia lower rates earlier that same day. What's interesting in that region, though, really is how much variation there is in policymakers outlook in terms of inflation and interest rates. So in Chile, the central bank came across much more dovish than was expected, whereas in Colombia, where inflation is much higher. While policymakers did cut interest rates by 25 basis points, they were really kind of driving home, I guess, the risks posed by wage pressures and services inflation in general. And elsewhere, central banks also seem largely unaffected by the Fed, to be honest. So we had the Czech National Bank earlier today cut rates by more than consensus expectations. And we also had both Poland and Thailand leave rates on hold, which again didn't come as a surprise. And we still think that both the central banks will begin cutting rates at some point this year. In India, we had the RBI leave rates on hold and they came across quite hawkish. But again, this wasn't really a surprise. They've been quite hawkish recently in general, and I think that was driven mostly by domestic factors more than any influence of the Fed.

Shilan Shah

Gareth, I wanted to bring you in on Asia. So how do our monetary policy forecasts there looking light of the Fed meeting?

Gareth Leather

Yeah, sure. So we've had inflation fall back quite sharply over the past year or so across Asia. And in most countries, not every country, inflation is now back to target. A lot of the falls have been due to this kind of the shock from food and fuel prices kind of dropping out of the annual comparison. We've also had core inflation falling quite a bit as well. So the inflation concerns are pretty much not completely gone away, but by and large central banks aren't too concerned about inflation. At the same time, you've got domestic demand has been very weak. Yeah, this aggressive tightening cycle, it's quite clear now that consumers and businesses are really starting to feel the pinch. So if you look at credit growth, for example, it's collapsed across the region over the past year. Retail sales growth is also very weak as consumers feel the pain. So you've really got the conditions now in place for an easing cycle to begin. I think the one factor really that's holding back central banks is worries about the Fed. They've been quite spooked by the falls and their currencies that you saw for most of last year and then again since the beginning of this year as well. And I think they'll be a lot more comfortable starting to cut once the Fed has also started to. So we recently pushed back our timing when we think the Fed will cut to May. And we think the most central banks in Asia will begin around then too.

Shilan Shah

I wanted to spend a few minutes talking about debt risks in frontier markets. And David, one interesting aspect of all of this, I think, is that some countries that have defaulted already haven't been able to restructure their debts. I know that this is something that you've been looking at. So can you explain perhaps what's been going on?

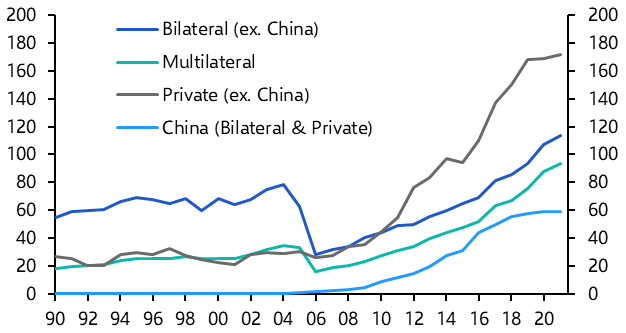

David Omajomolo

Yeah, sure. So there's three particular countries that come under that category in terms of having struggled to restructure their debts. So that's Ghana, Zambia, and Ethiopia. And if we take Ethiopia, they defaulted on their debts, I think it's over three years ago now. And that was followed by Zambia and then Ghana. But despite that, there's been relative differences in how quickly they've been able to come to agreements with private creditors and bilateral creditors as well. The reason for these differences are stemming from what has become an increasingly crowded creditor landscape in terms of those offering financing to these countries. So that's one aspect. So the rise of private bondholders, the reduced influence of multilateral and bilateral creditors. But the other elephant in the room has been China, which has gathered quite a lot of attention. They whilst bilateral lenders influence have decreased in aggregate. China's influence in terms of the loans that they're giving has increased. And that kind of comes to the relative differences we've seen in the speed of restructuring. We found that private bondholders, China and bilateral creditors that don't include China are increasingly coming to blows regarding the debt relief that they are agreeing with these different countries and how comparable each side's respective relief is in terms of generosity. So that's thrown a span in the works for Ethiopia, in particular recently, and for Zambia. On Ghana's front, it should be said that their talks are still taking a long time relative to like the recent past. But because of their reduced exposure to China, their talks have been much quicker than Ethiopia and Zambia, for example. And I think the one conclusion that I stated in a recent publication was the kind of multilateral system itself as a process to help bridge these gaps between these different creditors is really not living up to its potential as in vital need of reform. And that's something that quite a lot of people have been discussing. And what this means for growth is just because most of these economies are going to be locked out of capital markets for longer. And they're increasingly reliant on concessional financing from say the IMF or World Bank, which have tight fiscal requirements. It means that growth is likely to be subdued to these countries. Just on the last point, just to bring in the subject of Kenya, who have been going through debt distress, and I've often looked at from a perspective of the risk of them being the next to default, they appear like they're not going to be defaulting anytime soon. They've been able to rely on concessional financing, tap up bond markets to ensure that they're not going to be defaulting. And I think it just underlines the fear that is perhaps among sovereigns that defaulting on your debt can lead to a bit of a cycle of very long and torturous negotiations.

David Wilder

That was David Omajomolo on Frontier Debt Risks. His new analysis looking at restructurings in Africa will be on the podcast page, along with a link to the complete recording of the Drop-in.

Check it out and do look out for the team's EM monthly drop in next one happening first week of March. But that's it for this week. We'll be back next week where Neil will undoubtedly be unpacking those CPI releases and we'll have much more on the global economy and markets. But until next time, goodbye.