The past few weeks have served as a rebuttal to those refuseniks who argue that macro doesn’t matter for markets. There have been at least three important events in which a macro understanding is essential to understand what comes next.

The first has been the announcement of coordinated monetary and fiscal stimulus in China. This has underpinned a surge in stock markets in both China and Hong Kong after a dismal 12 months. You can read a detailed take here, but the key point is that while there appears to be a concerted effort underway to support the economy, we have yet to see much in the way of policy detail – or, in some cases, anything beyond wire reports of planned measures.

This is particularly true of steps to support household consumption, which are by far the most important part of the fiscal package – and, since fiscal policy is the most powerful weapon in the Chinese government’s armory, the most important part of the overall plan. Until we have official confirmation and details of the measures, we will refrain from making changes to our forecasts. We continue to expect a modest cyclical rebound in economic growth in China over the next couple of quarters, but remain of the view that structural headwinds will create a significant impediment to growth further out. Accordingly, while we remain cautiously optimistic that China’s equity market will hold on to its recent gains, and perhaps even extend upon them in the near term, given the economy’s structural challenges, we still think the stock’s market’s long-run prospects are poor.

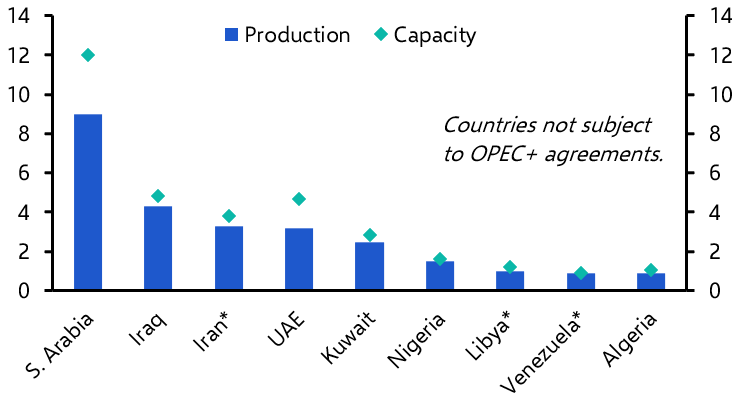

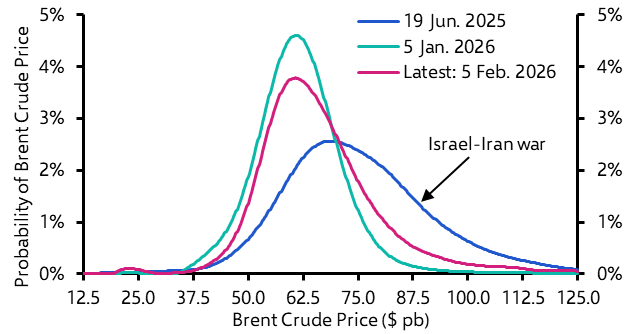

The second important event has been the escalating conflict in the Middle East. This has inevitably caused oil prices to spike over the past week, with Brent crude rising to just under $80pb. Once again, an understanding of the macro situation – as well as the delicate regional political situation – is necessary to navigate the path ahead. Iran is responsible for about 4% of global oil output. The concern is that Israel could retaliate against Iranian missile strikes by targeting the country’s oil facilities, hence the reaction in oil markets. These fears were further stoked by comments from President Biden on Thursday evening suggesting that such a strike was “under discussion”.

However, the bigger picture is that other major oil producers are sitting on significant amounts of untapped capacity. This is particularly true of Saudi Arabia, which is currently pumping 8 million barrels of oil a day (mbpd), when it could be pumping up to 12mbpd. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Oil Production vs. Capacity (August 2024, Mn. BpD) |

|

|

| Sources: LSEG Data & Analytics, Capital Economics |

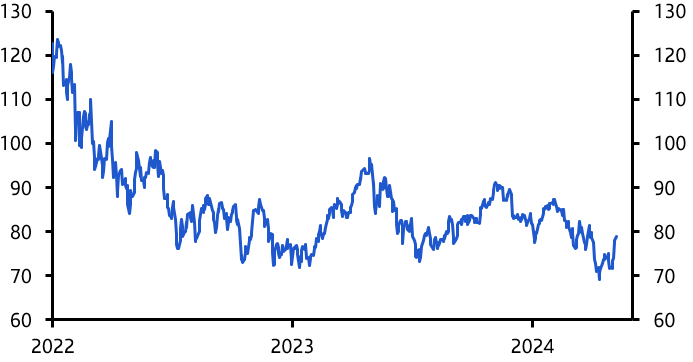

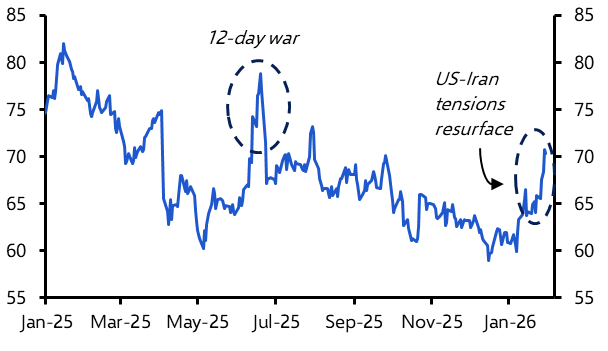

The restrictions on supply are part of a broader effort by OPEC members to shore up prices. But this strategy has so far failed, in part because of weakening demand from China. While oil prices have spiked over the past week, they are broadly unchanged from a year ago and are actually a bit lower than they were at the end of August. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Brent Crude Price ($pb) |

|

|

| Sources: LSEG Data & Analytics, Capital Economics |

Crucially, from the perspective of Saudi Arabia’s government, prices remain below the $90pb level that is needed to balance its budget and are only just about the level needed to avoid running a deficit on the current account of the country’s balance of payments. The Kingdom is learning the hard way that developing its non-oil economy is expensive and may be reaching the limits of its tolerance for a policy of constrained supply.

This being the case, it is possible that Saudi will respond to any disruption to Iranian oil output by increasing its own production, thus offsetting the hit to global supply. It goes without saying that oil prices will remain sensitive to developments in the Middle East, which are extremely difficult to predict on a day-to-day basis. But those banking on a sustained rise in oil prices may ultimately be disappointed.

The third significant development surrounds the incoming macro data. In the US this continues to paint a picture of an economy that is cooling rather than collapsing. The ISM manufacturing survey fell in September, but the equivalent services survey jumped. In the labour market, the quits rate continued to edge lower in August, suggesting that workers are becoming more cautious about their ability to find new jobs, but vacancies rose in the same month and September’s employment report was stronger-than-expected on pretty much every front.

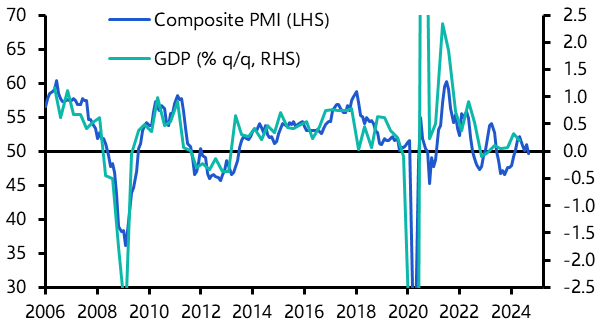

In contrast, the data from the euro-zone have been much weaker. The final composite PMI for September was revised up from its flash reading but is still consistent with a stagnation in GDP in Q3. (See Chart 3.) Moreover, the PMIs from Germany were even weaker and the challenges facing key parts of its manufacturing sector, notably autos, are intensifying.

|

Chart 3: Euro-zone Composite PMI and GDP |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Data & Analytics, Capital Economics |

All of this is important because it will influence the next move by central banks. Having cut by 50bps at September’s FOMC meeting we expect Fed officials to revert to smaller 25bps cuts in November and December. This view was given support by Jerome Powell, who recently said the relative strength of the US economy meant the Fed doesn’t “need to be in a hurry to cut”. The past week has seen a significant shift in market pricing, with investors pricing out around 50bps of rate cuts over the next 12-18 months and moving closer to our own view that the Fed funds rate will fall to around 3.00-3.25% by end-2025.

In contrast, having previously signalled its intention to keep interest rates on hold at its October meeting, we now expect the ECB to cut them by 25bps to 3.25%. And with inflation set to remain below the ECB’s 2% target next year, we expect additional 25bps cuts at every meeting of the Governing Council through to the start of the second quarter next year, taking its benchmark policy rate to 2.5%.

Stepping back, while events such as the spiraling conflict in the Middle East and policy stimulus in China can shift markets, it is developments in the real economy and the corresponding actions of central banks that ultimately anchor them. With this in mind, perhaps the biggest question of all is how far interest rates will be cut in this cycle. This brings us to the thorny question of what has happened to neutral interest rates. It is something I will tackle in my note next week.

Related analysis

I discuss China’s stimulus, the Middle East conflict and the outlook for Fed policy with Raymond James CIO Larry Adam in the latest episode of The Weekly Briefing. Listen here.

Questions on these themes have already been coming in ahead of our Drop-In on the global economic and market outlook this Tuesday. Register here for the 20-minute online briefing to get answers from Chief Global Economist Jennifer McKeown and Deputy Chief Markets Economist Jonas Goltermann to your questions.

Our US Economics Weekly put the debate over the Fed’s next policy steps in the context of a red-hot payrolls report and ISM services index releases.

Chief Europe Economist Andrew Kenningham addressed the puzzle over the rise in the euro-zone household saving rate.