2025 has taken little time to get going, with more evidence of the US’ relative economic strength, weakness in Chinese equity markets, and a dramatic sell-off in DM bond markets – not least gilts. And that’s all before Donald Trump is sworn in. In this week’s note I summarise some of the questions we’re being asked most often by clients in these opening stages of the year, and sketch out the answers.

Will US outperformance continue?

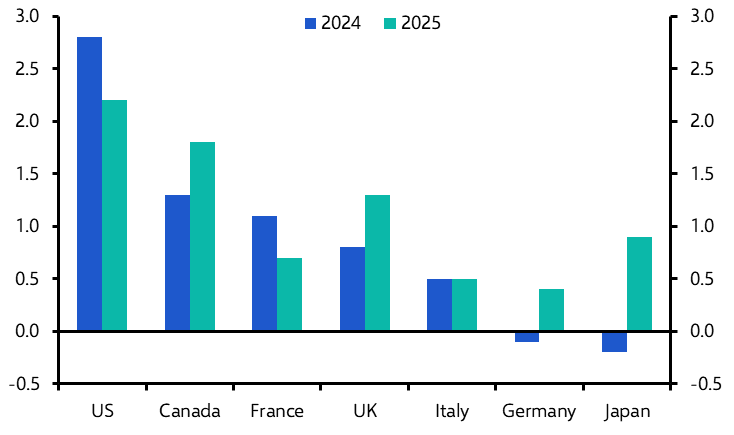

Yes, but this will be due in large part to weakness in other large advanced economies rather than a strong performance by the US. We expect the US economy to grow by 2.2% in this year, a bit below the 2.8% expansion it is likely to have recorded in 2024. However, full-year growth of just over 2% will conceal a drop in growth to mid-1% q/q annualised in the middle of this year as the combined effects of higher tariffs and migration curbs drag on activity. Accordingly, the sustained outperformance of the US over its peers will primarily be the result of continued weakness elsewhere. We expect the UK economy to grow by 1.3% this year, Japan by 0.9% and the euro-zone by just 0.8%. The result will be another year in which the US is the fastest growing major developed market – but one where growth falls short of some of the more bullish forecasts. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Real GDP (% y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics. |

Will inflation return?

Inflation will continue to edge lower in most advanced economies – with one important exception. The great inflation surge of the past four years is best viewed as the result of several shocks. The pandemic lockdowns and accompanying shifts in spending patterns were the most important, but these were then followed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a subsequent surge in energy prices, particularly in Europe. These shocks have largely worked their way through the system and are now fading. Central banks have made several missteps but deserve credit for keeping inflation expectations well anchored. The result is that inflation pressures should continue to ease in most economies this year. We expect headline inflation to end the year lower than where it started everywhere – but not in the US. This reflects the effects of the higher tariffs that we have assumed in our forecasts. To be clear, tariffs are best thought of as causing a step-change in the level of prices rather than a continuing increase in inflation. Assuming tariffs are not ratcheted higher each year, then the effect on inflation should drop out after 12 months. But higher tariffs may be enough to push US CPI inflation back above 3% over the second half of this year, which would make life uncomfortable for the Fed officials (something to which I’ll return shortly).

Will Donald Trump succeed in pushing through additional fiscal stimulus and tax cuts?

It’s doubtful. The US fiscal position is now in a radically different place to where it was at the start of the first Trump administration. The budget deficit is running at around 6% of GDP and federal debt is above 100% – and all this is happening in an economy that is at full employment. It is likely that the 2018 package of tax cuts, which was passed during the first Trump administration and is due to expire this year, will be extended. But any attempt to pass further deficit-financed tax cuts is likely to incur the wrath of the bond market (and possibly Congress). Accordingly, if the Trump administration is serious about additional tax cuts (including to corporate taxes and taxes on tips) then it will have to either cut spending or raise revenues from other sources. The former is unlikely, at least to a significant degree, the latter is possible (particularly if the administration is intent on raising tariffs). But this would simply shift the burden of taxation between sectors – it would not represent a fiscal stimulus. The macroeconomic consequences would depend on how the “fiscal multipliers” of the various tax cuts and tax hikes played out, but are likely to be relatively small.

How far will central banks cut rates?

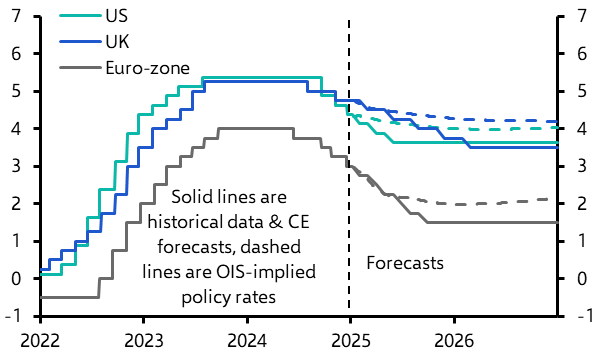

Central banks will lower interest rates further but most will move at a relatively gradual pace. While we expect inflation to fall over the next 12 months, progress will be slow and several risks remain. This is particularly true in the US, where the threat of loose fiscal policy and higher tariffs has unnerved the Fed. It is also true in the UK, where increases to the minimum wage, household utility bills and employer payroll taxes will slow the pace of disinflation. If nothing else, the past several years have underlined the importance of keeping inflation expectations well anchored. Therefore, barring a collapse in growth, central banks will remove policy restriction only gradually. With that said, the substantial repricing of rate expectations over the past month or so means that our forecasts for interest rates now sit below what is currently priced into markets. (See Chart 2.) We believe that the Fed will carry out two 25bps cuts to interest rates this year but, at the time of writing, markets are pricing in barely more than one further cut in 2025. Elsewhere, we expect interest rates in the UK to be lowered to 3.75% by the end of the year, whereas the market is pricing in a fall to just over 4%. And in the euro-zone we forecast a drop in the key policy rate to 1.5% this year, compared to the 2% priced into markets. Central banks will move gradually, but the sell-off in short-dated bonds since the turn of the year may have gone too far.

|

Chart 2: Policy Interest Rates (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics. |

Will efforts to reinvigorate China’s economy succeed?

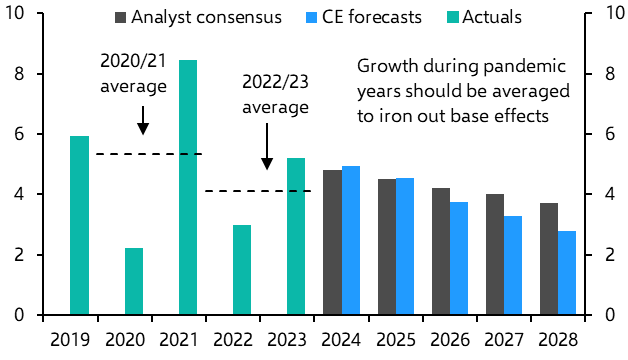

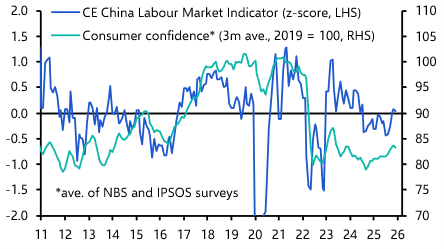

A rebound in growth in the near term is likely, but we doubt this will be sustained. China’s leadership stepped up efforts to deploy unused budget funds at the end of last year and there is already some evidence from the business surveys that this has provided a boost to activity. Property sales are also recovering, albeit from depressed levels. Fiscal and monetary policy are likely to be loosened further this year, with support likely to be front-loaded in the first and second quarters. This should give a further boost to activity. But the scale of policy support will be relatively small and the measures that have been floated so far will do little to address the structural issues that are increasingly weighing on China’s economy. The underlying issues are well known: a high savings rate, a low consumption rate and an excessive reliance on investment and exports as sources of demand. But the support measures that have been announced will do little to tackle these issues. Indeed, in some respects they could deepen China’s structural challenges: fiscal spending on investment will probably increase this year. The fact that the Trump administration is likely to impose punitive tariffs on imports from China will only add to the headwinds facing its economy. The upshot is that we expect growth to accelerate in the first half of this year, before slowing in the second as the effect of policy support fades and structural pressures reassert themselves. We remain more downbeat than most on China’s medium-term outlook. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: China GDP (Official Measure, % y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: CEIC, LSEG, Capital Economics. |

How bad is the outlook for Europe?

Pretty bad. The consensus forecast for growth this year has been slowly reduced in recent months, but we still stand towards the bottom of the analyst range. We expect GDP to grow by just 0.8% this year. In contrast to the euro crisis of the last decade, when the problems were concentrated mostly in the region’s smaller economies, they are now centred on the Big Three: Germany, France and Italy. What’s more, while there is an element of cyclical weakness at play, many of the challenges are structural in nature. The long list of issues includes high energy costs, a declining manufacturing base, moribund consumer spending and (Germany aside) fragile fiscal positions. The policy architecture also remains a concern, with fiscal and banking union still incomplete. None of this is to say that another euro crisis is likely – the ECB now has sufficient tools to stand behind national bond markets. But it does mean that the major economies in the bloc will remain in near-recessionary conditions throughout this year. Meanwhile, in contrast to the situation a decade ago, the peripheral economies of Spain, Portugal and Greece are now in much better shape. For anyone in search of a positive growth story in Europe, these are the places to look.

What should we make of the recent sell-off in the UK government bond market?

In truth, the scale of the sell-off in gilts is a little puzzling. Yields on government bonds everywhere have increased since the start of the year but the rise has been particularly sharp in the UK. And yet there has been nothing in the recent data to suggest that the outlook for UK inflation has deteriorated markedly in comparison to other advanced economies. The UK’s fiscal position is hardly a picture of health, but it is no worse than that of France, Italy and the US. It may be that the UK’s comparatively heavy reliance on foreign creditors has played a role. Regardless, the sell-off is a major headache for the government, which according to our estimates, will see the headroom against its fiscal rules eradicated if borrowing costs remain at these levels. The worry is that this could set in train a vicious cycle of deepening concerns about the UK’s fiscal position, which in turn leads to a further rise in government bond yields, and so on. I’ve written before that fiscal sustainability is as much about perception as it is policy. It’s a lesson the UK is learning again, but it won’t be the last DM government to be schooled on this.

In case you missed it:

- Our UK Fiscal Headroom Monitor provides the timeliest estimates of how much fiscal space the chancellor has.

- In the midst of Friday’s payrolls-induced sell-off in Treasuries and US equities, we explained why we don’t expect this to be a trend in 2025.

- The Starmer government is briefing its intention that the UK takes a leadership role in the global AI revolution. Our proprietary AI Economic Impact Index shows how well it is positioned to do so.

- Deputy Chief North America Economist Stephen Brown explains what awaits Canada’s economy when Donald Trump returns to office.