Maybe it’s the approach of Halloween that spooks the bond market so much. Two years ago, the UK government’s “mini Budget” triggered a meltdown in the gilt market and ultimately ended Liz Truss’s short but chaotic time as Prime Minister. Government bond yields were surging this time last year amid concerns about fiscal sustainability across advanced economies and talk of the return of the ‘bond vigilantes’. And borrowing costs have been rising again in recent weeks. How much fiscal trouble are developed economies in?

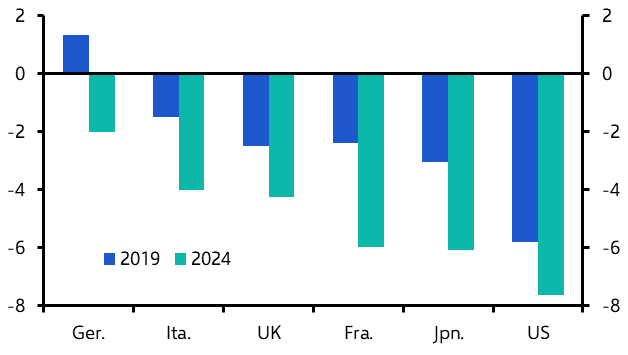

The marked deterioration in the public finances of advanced economies since the pandemic is made clear in the IMF’s latest Fiscal Monitor, which compares its forecasts for budget balances of major advanced economies this year with how they stood in 2019. (The IMF’s fiscal data differ from national measures, but since they attempt to iron out definitional inconsistencies they make cross-country comparisons easier.)

It makes for scary reading: based on the IMF’s definition, budget balances have deteriorated by an average of 2.5% of GDP since 2019. In France, the deficit is on track to hit 6% of GDP this year. In the US, it is likely to exceed 7% of GDP. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: General Government Budget Balance (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

|

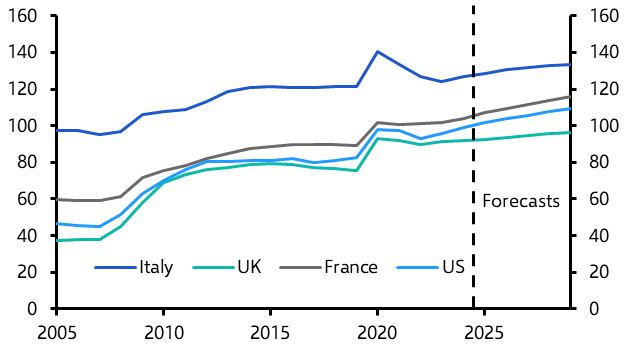

As a result, government debt ratios are now at or close to their highest levels since the IMF started producing this data in 1980 in every country apart from Germany (surprise).

What’s more, while the Fund forecasts debt ratios will increase at a more modest pace in future years, this is predicated on governments enacting measures to tighten fiscal policy. Given how much they have fallen short against their plans to reduce deficits in recent years, this could be regarded as a triumph of hope over experience.

|

Chart 2: Net General Government Debt (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

|

What could go wrong

The key question is whether any of this matters. One concern is that, with economies operating at full employment, this fiscal largesse means that government spending crowds out private investment, which is more productive. There is probably something to this, although it is hard to prove empirically.

The more immediate concern regards fiscal sustainability.

This is a tricky concept in developed economies. Since governments issue debt in local currencies, national central banks can stand behind sovereign bond markets. Accordingly, unlike in some emerging economies which still issue in foreign currencies, there is little chance of governments defaulting outright on their debt. (The situation in the euro-zone is complicated by the absence of fiscal union to accompany monetary union, but various backstops combined with legal fudges have permitted direct purchases of sovereign debt by the European Central Bank, reducing the risk of an outright default by a euro-zone government.)

Rather, problems emerge when faith in the government’s commitment to fiscal rectitude diminishes, causing bond yields to rise sharply and forcing policymakers to take remedial action to restore credibility and prevent the fiscal arithmetic from spiralling out of control. This was the case in the US in the mid-1990s, when a jump in yields prompted the White House to tighten fiscal policy, an episode that led to Clinton advisor James Carville’s oft-quoted line about wanting to be reincarnated as the bond market (“You can intimidate everybody”). It was also the case in the UK two years ago, albeit with the added twist that the drop in bond prices turned into a crisis, as liability-driven investment strategies by pensions created a vicious circle of margin calls and more bond selling.

Why messaging matters

The challenge comes in knowing at what point the patience of the bond market runs out. There is no clearly defined red line beyond which a crisis becomes inevitable. Instead, several factors play into the maintenance of confidence and keeping the bond market onside. One of these is policy substance: the government that ramps up spending or slashes taxes on top of an already precarious fiscal position is asking for trouble. But the lesson from the Truss debacle is that tone and optics also matter. The violent reaction in markets was not just a response to expansionary measures themselves, but also the manner in which they were announced. The UK’s fiscal watchdog was side-lined and anyone suggesting that unfunded tax cuts threatened long-term fiscal sustainability was dismissed as an adherent of “abacus economics”. This created the general impression that the fiscal guardrails had come off.

The Budget that new UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves is due to announce this week is widely expected to include plans to raise borrowing to increase investment. Provided that this comes alongside a commitment to maintain fiscal discipline and get a grip on day-to-day (i.e. non-capital) spending, I suspect the gilt market will take this in its stride. A repeat of the crisis of two years ago is unlikely.

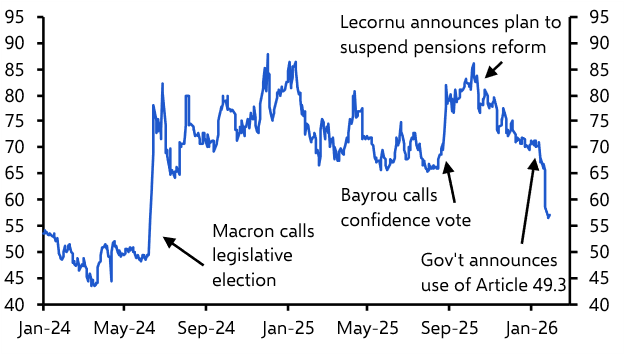

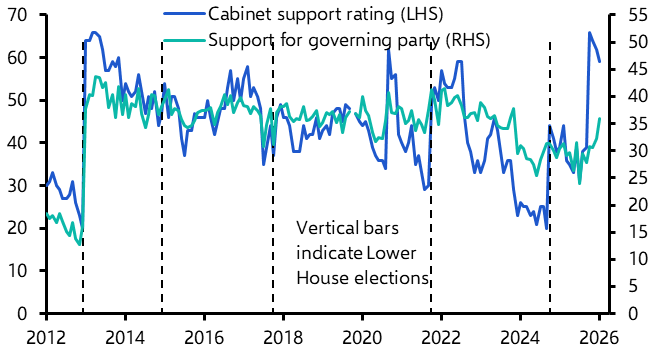

Instead, the most vulnerable economies are those whose governments appear most at risk of shifting away from the narrative of fiscal rectitude. The most obvious is the US, where a Trump victory in next month’s elections would increase the chances that unfunded tax cuts could be tabled, particularly if Republicans also prevail in down-ballot races (This new analysis, prepared in response to frequent client questions, explores the reality of US fiscal risks). But there are also acute fiscal risks in Europe too, particularly France and Italy (the latter of which continues to fly under the radar).

The Truss episode was a teachable moment for advanced economy governments, and the threat of the bond market meting out similar punishment should act as a deterrent against untrammelled fiscal expansionism.

But, in a world of wide and widening deficits, the risk of government miscalculation is acute.

In case you missed it:

All our UK Budget coverage can be found on this dedicated page, including registration details for our post-statement online Drop-in briefing on Wednesday. South Africa’s Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement is also due that day. Register here for that session.

Is inflation whipped? Our latest Global Inflation Watch shows why we think core inflation in advanced economies will follow headline rates back to target by mid-next year. Register here for a Thursday Drop-In which will explore the inflation outlook and implications for the bond market.

The market swung around to our North America team’s long-standing – and ultimately correct – view that the Bank of Canada would cut rates by 50 basis points in October. But the Bank’s policy outlook is now clouded by the government’s stringent new immigration targets.

The IMF’s US growth upgrades and euro-zone downgrades are another marker of the American economy’s outperformance. We made the case for ongoing US outperformance in a June report which also showed why returns from US equities will underperform over the medium-term.