Last week I participated in a small roundtable with investors and economists. It was notable – if not entirely surprising – that the broad topics of conversation chimed with a lot of recent discussions I’ve been having with Capital Economics' clients:

How should we think about the post-COVID economy?

This is a big question, and one that will be the subject of countless PhD theses to come. On the demand side, it is clear that outsized fiscal support during the pandemic and in its immediate aftermath played a key role in sustaining consumer spending. This fiscal expansion manifested itself in several ways, including the “excess savings” that were accumulated by households and which have helped support spending over the past three years. With that said, while the pandemic served as a timely reminder of the power of fiscal policy in sustaining demand, it’s possible to have too much of a good thing. The policy mix in most advanced economies is now unbalanced; budget deficits are too large and interest rates are too high. Advanced economies would be best served by rebalancing in favour of tighter fiscal policy and looser monetary policy.

None of this is controversial. Economists have models that are oriented around analysing shifts in demand. And while there are clearly political challenges to overcome, most would agree that a recalibration between fiscal and monetary policy would be beneficial, not least in putting public finances on a more sustainable footing over the long run.

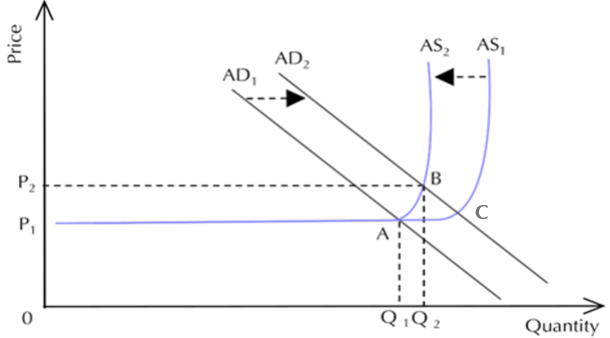

But the key to analysing the post-COVID economy lies in understanding developments on the supply side. We set out a framework for thinking about this a couple of years ago. In simple terms, the pandemic caused two things to happen. The first was that the dislocation caused by rolling lockdowns in advanced economies caused the aggregate supply curve to shift inwards. At the same time, monetary and fiscal expansion during the pandemic caused the aggregate demand curve to shift out. This moved economies from an equilibrium of A in Chart 1 to a new equilibrium of B – and to a place where small changes in demand created large moves in prices rather than output. This helps to explain the great inflation of 2021-22.

|

Chart 1: Aggregate Demand and Supply Framework |

|

|

| Sources: Capital Economics |

However, as the dislocation caused by the pandemic has faded, the aggregate supply curve has shifted back out. In the US, this has been helped by a surge in immigration, which has boosted the labour supply. This has shifted economies to a new equilibrium, where output is higher but inflation/prices are lower (labelled here as C).

This is, of course, a highly stylised model. But it does help to think through the various shocks and shifts that economies have experienced over the past five years. It also leads us to an important conclusion: the potential for a supply-side recovery raises the possibility that inflation can be brought to heel without crushing demand and tipping economies into recession. This is the path to a soft landing.

Why has Europe lagged the US?

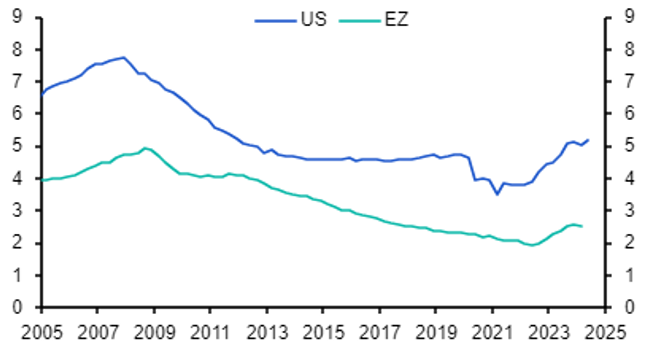

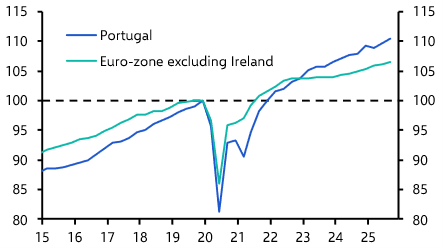

The underperformance of Europe relative to the US is clear in the data. Whereas the US economy is now nearly 10% larger than it was pre-COVID, euro-zone GDP is only 3.9% larger. One explanation we often hear is that the prevalence of long-term fixed rate mortgages have shielded US households from the effects of higher interest rates to a greater extent than in Europe. However this doesn’t square with the data. As Chart 2 shows, debt servicing costs of households have risen further in the US than they have in the euro-zone.

|

Chart 2: Household Interest Expense (% of income) |

|

|

| Sources: LSEG Data & Analytics, Capital Economics |

Instead, the underperformance of Europe is more likely due to a combination of different factors. For a start, fiscal support in Europe was generally smaller than was the case in the US. At the same time, while the US saving rate has now fallen back to pre-COVID levels, in Europe it has risen. In addition, the energy shock that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to a huge deterioration in Europe’s terms of trade that manifested itself in a hit to real household incomes. Since the US is now a net energy exporter, and does not import natural gas from Russia, it was not subject to the same shock. Crucially, the energy shock appears to have accelerated structural decline in parts of the European economy that was already underway.

Some of these pressures will ease over time. In particular the surge in the household savings rate in Europe is difficult to explain and may not be sustained. But structural headwinds will persist, particularly those facing German industry. Accordingly, we expect that the euro-zone economy will continue to experience extremely low rates of growth and our GDP forecasts remain below that of the consensus. Moreover, the structural nature of this weakness will limit the ability of the European Central Bank to reinvigorate growth by cutting interest rates. Nonetheless, we continue to expect a relatively gradual pace of policy easing in Europe, with euro-zone interest rates lowered by 25bps each quarter to around 2.5% by the end of next year.

What are the key risks to the outlook?

The biggest threat is a hard landing or recession in the US. However, while there are some signs of stress among lower income households, our view remains that a soft landing is still the most likely scenario. Likewise, the US election presents an obvious risk to the outlook. At face value, the measures floated by Trump on the campaign would reduce US GDP and raise US inflation, although we suspect that in practice these will be diluted. (See here.)

Some participants at the roundtable flagged concerns about China. However while China’s economy is clearly struggling, its problems are mainly structural in nature. We do not anticipate a sudden collapse in activity that would bring down the rest of the global economy.

Looking back over the past two decades there have been two types of shocks that have caused major economic disruption. The first has been non-economic in nature. The COVID-19 pandemic created huge dislocations on the supply side of the global economy, collapsing output and leading to a subsequent surge in inflation, while Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused a sharp rise in energy prices, particularly in Europe. These types of shock are by nature almost impossible to anticipate in advance. The Middle East is a constant source of risk but is only likely to cause significant consequences for the global economy if it leads to direct disruption to global oil supplies. Likewise, the risk of a confrontation between China and Taiwan continues to linger in the background but, while potentially catastrophic, could take many forms. Understanding the nature of these risks is more important than anticipating them in the first place.

On the macro-financial front, commercial real estate markets appear to be finding a floor and, in any case, we were always sceptical that they had the potential to cause systemic problems for the global financial system. It is a reasonable assumption that there are risks lurking in pockets of private credit markets and shadow banks, but these are by definition shadowy and difficult to assess. We continue to anticipate the bubble in AI and related stocks will inflate further, but when it pops the underlying technology won’t disappear.

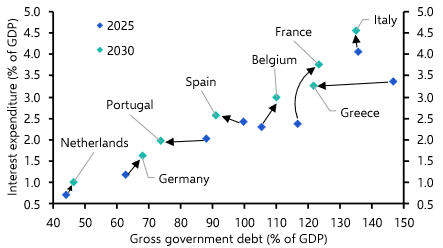

Perhaps the biggest risk lies in shaky public finances across advanced economies. Budget deficits have ballooned and public debt burdens are high and rising. The ultra low interest rate environment that helped to sustain fiscal positions in the pre-COVID era has ended. The key lesson from the Truss debacle in the UK is that the attitude and tone of policymakers is critically important. In addition to the forthcoming election in the US, national elections are due next year in Germany. Meanwhile, France’s new government may struggle to pass a budget which delivers the fiscal tightening needed to put its public debt on a sustainable path.

If any of this gives rise to a sense of fiscal drift – or, in the case of Germany’s elections, produces a result that threatens the integrity of the eurozone – then the situation in global bond markets could get ugly quickly. Sometimes the biggest risks are hiding in plain sight.

Related analysis, data and events

Our Economic Momentum Indicators were updated on Friday and give you at-a-glance assessments of recession risks faced by eight major DM economies. This report explains the rationale for these indicators, explains current readings and provides some methodology.

Must-read analysis around the threat posed by government debt positions can be found on this key issues page.

Our latest Europe Economic Outlook highlights the region’s near-term struggles while Chief Europe Economist Andrew Kenningham explained Germany’s structural problems in this March report. The team will be holding a Drop-In on Tuesday to brief clients on the outlook – register here for the 20-minute online session