Elections in the UK and France over the past few days have produced radically different outcomes, with the centre-left Labour Party securing a landslide victory in the UK, but the vote in France ending in a hung parliament with a three-way split between left-wing, centrist and hard-right parties.

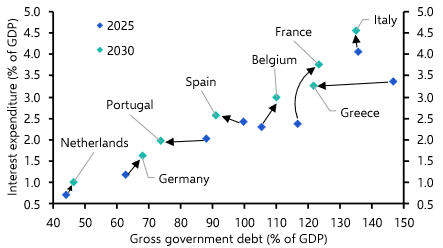

Yet, from an economic perspective at least, both elections have been framed in similar ways. Much ink has been spilled in the UK about how a lack of “fiscal space” will constrain the incoming Labour government. Likewise, it is clear there is insufficient fiscal room to push through the tax and spending promises that have been made by both the left and the right in France.

However, while it is true that the public finances of both France and the UK are looking shaky (as I noted a few weeks ago), I am not sure that this is the correct way to frame the macro debate in either country. The most pressing issue that policymakers must address is not fiscal in nature – it is the chronically low growth rates of their economies.

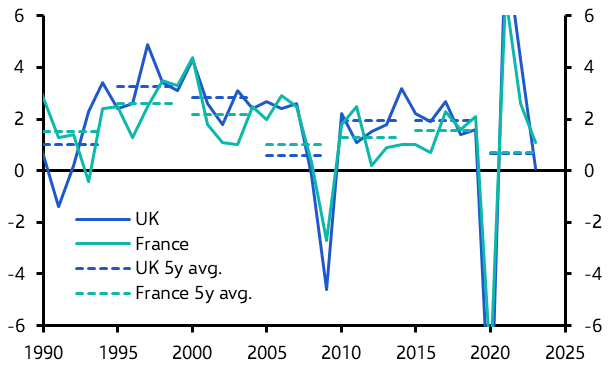

Over the past four years the French economy has grown by only 3.3% while the UK economy has expanded by just 1.8%. Viewed over a longer horizon the trend towards slow growth in both countries is clear. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Real GDP (%y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

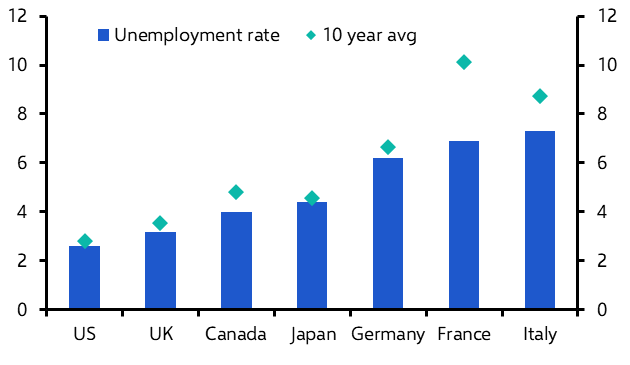

What’s more, it is not obvious that the cause of weaker growth is a lack of demand that needs to be addressed through fiscal expansion. On the contrary, weak growth in both the UK and France – and indeed most advanced economies – has come alongside low rates of unemployment by the standards of each economy. (See Chart 2.) This stands in contrast to the period after the Global Financial Crisis, when soaring rates of unemployment were a clear sign that the principal cause of economic weakness was deficient aggregate demand. Loosening fiscal policy against a backdrop of low unemployment is more likely to result in higher inflation than faster growth.

|

Chart 2: Unemployment Rate (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

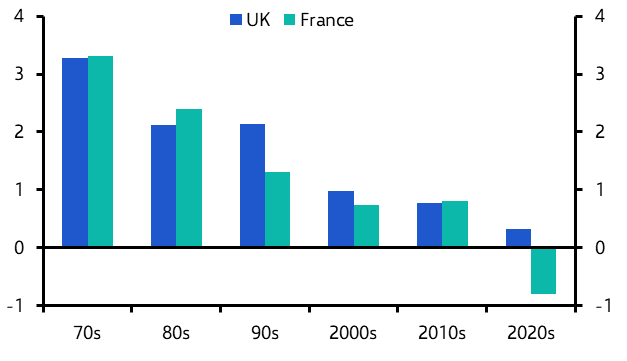

Today the problems lie more on the supply side. This has been reflected in the relatively low rates of productivity growth seen in both countries this century. (See Chart 3.) Indeed, during the 2020s, productivity has actually fallen in France.

|

Chart 3: Productivity (%y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

The sustained weakness of productivity growth has a direct counterpart in the squeeze in real incomes and living standards that has fed voter dissatisfaction in both countries. Reinvigorating productivity growth therefore holds the key to reviving economic fortunes, and restoring public trust in government.

A package of reforms is therefore required to target supply problems in both countries. These cover a multitude of different areas, and the relative importance of each differs between countries. But they can be grouped into three broad categories of measures:

- Those to increase labour supply;

- Those to lift investment; and

- Those to stimulate what economists call ‘multi-factor productivity’, a gauge of the efficiency with which capital and labour are put to work.

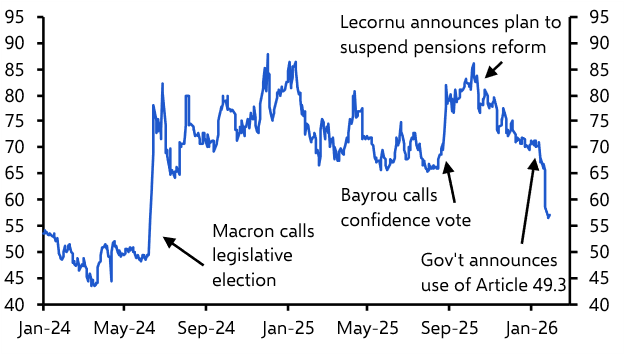

In France, a key focus of labour market reform has been efforts by President Emmanuel Macron to raise the age of retirement. Threats by parties on both the left and the right to reverse these reforms would be a significant retrograde step.

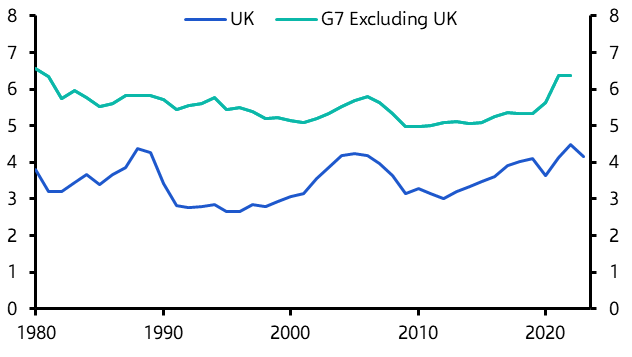

The UK has its own labour supply problems, which have not been helped by Brexit. But raising its chronically low investment rate is also critically important. Addressing comparatively low rates of residential investment is key here. (See Chart 4.) If the Labour government is serious about reinvigorating economic growth then planning reform must be a priority. Finally, there are many factors that influence multi-factor productivity but crucial for all advanced economies over the next decade will be to develop a strategy for embracing and diffusing AI.

|

Chart 4: Residential Investment (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refiniv, Capital Economics |

A critical point in all of this is that there are many linkages and interdependencies between these areas. On their own, supply-side reforms can make a difference, but success will depend on tackling a multitude of issues in a joined up way. This in turn requires stepping back and viewing the challenge through the lens of macroeconomics. For example, generating a sustainable increase in the UK’s investment rate also requires a corresponding increase in domestic savings to fund it. Reforms to stimulate investment must therefore come alongside broader measures to raise savings, such as pension reform.

Supply-side measures are notoriously difficult to implement and require time to take effect. The challenge facing governments across advanced economies is therefore significant and the likelihood of success is tempered by the fact that few policymakers have correctly articulated the problem from a macroeconomic perspective. This is particularly true in France, where fiscal populism appears to have trumped supply-side reformers. But neither economy suffers a chronic shortage of demand. A lack of fiscal space is therefore not a major impediment to achieving what should be the central mission of all governments, which is to raise the rate of economic growth.

In case you missed it:

All our key analysis of the French election and France’s public debt problems can be found here.

Our UK team assessed the outlook for housing reform under the Starmer government.

Our Markets team will be briefing on the outlook for equities, bonds and currencies in a Drop-In on Tuesday at 1000 ET/1500 BST. Register here for the 20-minute online briefing.