You don’t need fluent French to understand what France’s finance minister was referring to when he warned of “un scénario à la Liz Truss” if the far right wins in upcoming legislative elections.

Bruno Le Maire’s warning about a repeat of the turmoil that hit the UK bond market in late 2022 came amid a sharp widening in French bond spreads on worries that a fiscally incontinent National Rally government would lead to France’s public debt situation deteriorating even more quickly.

A semblance of calm has returned to the market, helped by conciliatory noises by National Rally (RN) leader Marine le Pen. But the spread of French bonds over their German equivalents remains at multi-year highs, reflecting the fragility of investor sentiment.

What’s more, this fragility isn’t exclusive to trade in French government debt: across advanced economy bond markets, a precarious balance exists between investors, who have taken the deterioration in public debt situations largely in their stride, and government borrowers, who have at least been paying lip service to fiscal rectitude.

This sets the backdrop for a run of elections across advanced economies over the second half of this year. Sandwiched between the two rounds of voting in France over the next few weeks is the general election in the UK. And once the dust has settled on voting in both countries, focus will quickly shift to November’s elections in the US.

It’s the deficits, stupid

For all the ink that is spilt over elections, the truth is that they rarely move the dial on long-term macroeconomic performance. To the extent that these elections will matter for their economies, it is because their outcomes risk upsetting that delicate balance between bond investors and governments.

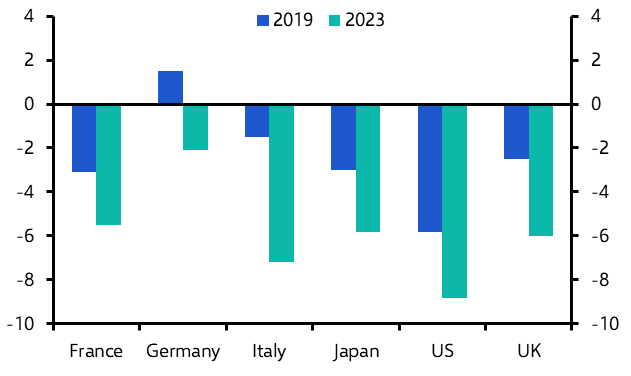

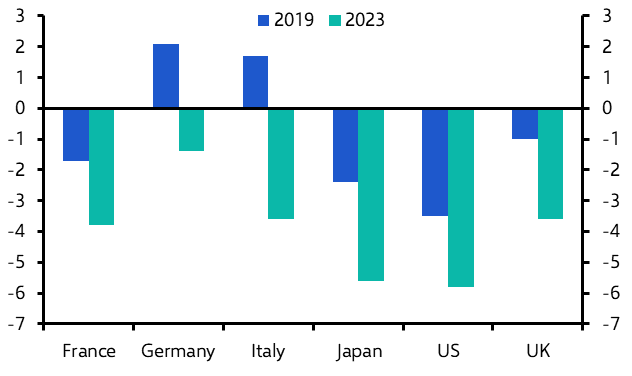

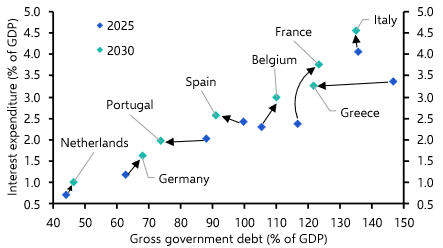

As we have argued before, fiscal support has been key to the resilience of advanced economies in the face of higher interest rates. Budget deficits across the G7 have widened by an average of over 3% of GDP compared to 2019. This partly reflects the effects of higher interest costs on government debt servicing. But primary budget balances – which exclude spending on debt interest – have also deteriorated substantially. (See Charts 1 & 2.) Meanwhile, at just under 100% of GDP in the US and UK, 110% of GDP in France, and close to 140% of GDP in Italy, public debt ratios are at multi-decade highs.

|

Chart 1: Headline Budget Deficits (% of GDP) |

Chart 2: Primary Budget Balances (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Maintaining fiscal sustainability against the backdrop of a heavy debt burden is essentially a confidence game – if investors believe that a government is committed to fiscal rectitude over the long term then they are generally willing to look through short-term increases in debt and deficits. But if this commitment comes into question then confidence is quickly lost, bond prices fall and yields shoot up – increasing government borrowing costs and making the fiscal position unsustainable. The rise in French yields over the past two weeks is significant – but the UK’s experience in 2022 shows how they could spiral further.

Accordingly, from a macro standpoint the most pressing issue around elections is what they mean for the conduct of fiscal policy. What do we know so far?

Labour’s fiscal disciplinarian

In the UK, leading figures within the Labour Party – which looks likely to sweep the Conservatives from office and form the next government – are going out of their way to reassure markets of their commitment to fiscal discipline. Its manifesto contained just over £8bn of spending increases – the smallest of any of the main parties – and these would be entirely financed by an equivalent increase in taxes. The shadow Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has also pledged to retain the current set of fiscal rules, which requires that public debt (excluding the Bank of England) should be forecast to fall as a share of GDP in five years’ time.

In order to meet this rule, the plans of the current government envisage a significant reduction in real government spending in unprotected areas from 2025-26, equivalent to around 75% of the cuts that were made during the austerity years of 2010-15. It remains to be seen whether a spending squeeze on this scale is politically viable for any party to pursue – or indeed whether it would even be necessary. It’s likely that markets would tolerate higher levels of borrowing if those funds were used to finance greater public investment. My hunch is that a Labour government will wait to see whether a broader push to reinvigorate growth – notably through planning reform – succeeds before making major changes to tax and spending, or revamping the UK’s fiscal rules.

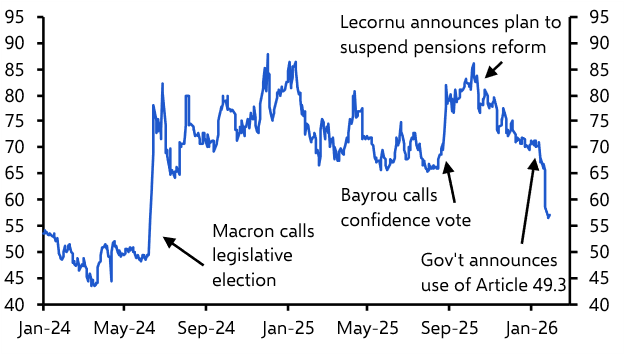

A political mess in France

The uncertainty surrounding elections in France is much greater. The first source of uncertainty relates to the outcome of the election itself. Opinion polls suggest that the RN is on course to win the greatest number of seats in parliament but not an overall majority – and its leaders have ruled out forming a minority government while other parties are unwilling to go into coalition with them. Meanwhile the New Popular Front (NFP) group of left-wing parties is on course to win the second largest number of seats, but would need the support of centrists to form a government. While the outcome of this jockeying remains unclear, a minority government of some form is a possibility.

The second source of uncertainty surrounds the fiscal policies that will be pursued by the next government. Both the RN and NFP have advocated significant fiscal expansions, but the extent to which they would actually do this in practice is unclear. The attempts over the past week by the RN to tone down some of its more radical rhetoric may be a sign that it would pursue more moderate policies in office. If so, that might suggest that, from a strictly fiscal perspective, a government led by the NFP is a greater threat. Its programme includes vast spending commitments and a rejection of the EU’s fiscal rules. Meanwhile, a minority government could result in either a continuation of the status quo or policy paralysis that creates further fiscal drift.

France is critically important not just because it is the euro-zone’s second largest economy but because it is the world’s fourth largest bond market. The fact that the ECB now has an expanded toolkit to stand behind sovereign bond markets and prevent contagion from spreading throughout the euro-system limits the risk of a wider financial crisis. However, the situation is delicate and the chances of a mini-fiscal crisis are high. As we argued last week, French bond spreads are likely to widen further over the coming months.

Stakes are highest in the US

If all of this sounds concerning then over the long term the stakes are arguably even higher in the US given both the size of its deficit and the centrality of its economy to the global financial system. The US government has more leeway to run large deficits given that it benefits from the “exorbitant privilege” of possessing the world’s reserve currency.

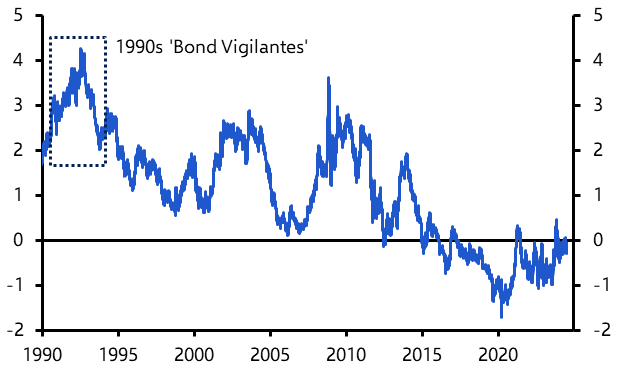

But the 1990s showed the limits of this privilege and the ultimate influence of the so-called ‘bond vigilantes’. New York Federal Reserve data show that the term premia on US government bonds rose to as much as 380 basis points in May 1992 – prompting James Carville to make his now-famous quip about wanting to be reincarnated as the bond market (“You can intimidate everybody.”) and the Clinton administration to focus on fiscal consolidation through the mid-1990s. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: ACM Estimate Of US 10-Year Treasury Term Premium (bps) |

|

|

|

Source: New York Fed |

That was then. Measured as a share of GDP, both the headline federal budget deficit and the primary federal budget deficits are now larger than they were at their peak in the mid-1990s.

Less than a decade after Carville’s utterance, then-Vice President Dick Cheney reportedly dressed down an increasingly nervous Treasury secretary, telling him that “deficits don’t matter”. If the US elections end in both a president and a Congress that are happy to keep on the current fiscal path, then the bond market could remind them sharply that they still do.

In case you missed it:

Chief Global Economist Jennifer McKeown outlined the risks around proposals that central banks stop paying interest on the reserves that commercial banks deposit with them.

After the S&P 500 hit our end-2024 target last week, our Markets team revised up our forecasts for this year and next, explaining why we think this equities bubble can continue to inflate for now.

Chief Asia Economist Mark Williams unpacked comments from the governor of the People’s Bank of China which hinted at monetary policy reform and helped explain why the Bank hasn’t cut rates in the face of weakening credit activity.