Soft growth, falling inflation, lower interest rates, bond market rallies, and an election bonanza – here are the key themes that will shape 2024.

Growth will undershoot the consensus. Economic growth is likely to be weaker than the consensus expects next year. In most countries this is due to the continued pass-through of tighter monetary policy to the real economy (the lengthening of debt maturities means that the pain of higher interest rates is being spread over a longer period). In some EMs this will be exacerbated by the unwinding of the positive shocks that boosted growth this year (including a bumper harvest in Brazil and a capex boom in India). Accordingly, our GDP forecasts are below consensus in all major economies and regions. This is particularly true in Europe, where our forecast for euro-zone GDP sits towards the very bottom of the consensus range.

The euro-zone and UK will continue to underperform the US. This is partly because Europe’s economy has had to contend with greater headwinds over the past year, the effects of which are still feeding through: higher energy prices are accelerating structural decline in some parts of European industry, and the region has been more exposed to this year’s global manufacturing downturn, the spillovers from which are now bleeding into services.

But policy settings are also very different. US fiscal policy has been more supportive than in Europe and is unlikely to tighten in an election year. In contrast, many European governments will have to tighten fiscal policy in order to meet EU budget rules. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank and Bank of England look set to keep interest rates at their peak for longer than in the US (more on this later) and households and corporates in Europe will continue to feel a larger squeeze from earlier rate hikes given the tendency towards shorter-term fixed-rate debt compared to the US.

All of this means that the euro-zone and the UK are likely to experience (mild) recessions in early-2024, whereas there is only a 50:50 probability of a recession in the US. One implication is that 2024 is likely to be another year in which the dollar stays stronger than most analysts appear to expect.

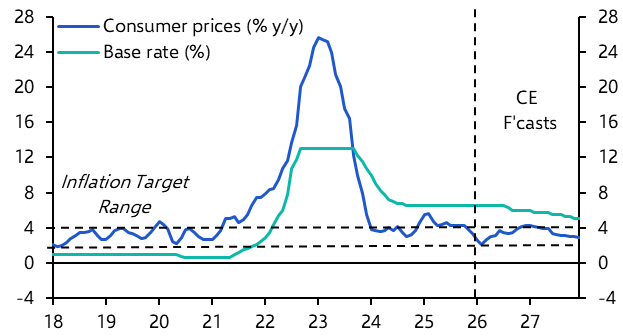

The great inflation surge will end. Inflation cycles are still being driven heavily by pandemic-related supply distortions. This is one reason why we have argued that the post-COVID inflation scare is more analogous to the inflation shock that followed World War Two than the inflationary surge of the 1970s. It follows that as pandemic-era distortions fade, inflation will continue to come down. The US will continue to lead the way, helped in part by large falls in the shelter component of CPI that we know are coming in 2024. Indeed, we think that US inflation will ultimately slow more quickly than Fed officials expect. But inflation will also drop across the euro-zone, the UK and other major DMs. To be clear, the era in which inflation has tended to undershoot central bank targets and where deflation risks dominated is now firmly in the rear-view mirror. But 2024 is likely to be the year where core inflation finally moves back towards central banks’ comfort zone of around 2%.

Interest rates will fall (nearly) everywhere. Just as the deflation era has been consigned to history’s dustbin, so too has the era of ultra-low interest rates. However, by the same token, a slowdown in inflation means that, all other things being equal, the real stance of monetary policy will start to tighten – right at the point at which economies are weakening. Accordingly, central banks across advanced economies are likely to loosen policy. The fact that the disinflationary process is more advanced in the US – and that there appears to be greater institutional hawkishness within the ECB – suggests that the Fed is likely to lead the easing cycle. Indeed, we think that rates in the US are likely to fall by more than markets expect. But the bigger picture is that, following the most aggressive tightening cycle in four decades, 2024 is likely to be the year that interest rates across the developed world turn. In addition to the Fed, we expect the ECB, BoE, BoC, RBA, RBNZ and the Riksbank to cut rates next year and for bond yields to fall across advanced economies. Likewise, we think that most EM central banks will cut interest rates, albeit at a slightly slower pace than markets currently anticipate. All of this will leave Japan as the main outlier – we’ve penciled in a one-off hike in interest rates in the early months of next year as policymakers take advantage of a narrow window to get rates out of negative territory.

Cyclical recovery but structural weakness in China. China will end 2023 in a stimulus-driven recovery that will last into the first half of 2024. This will be driven by greater fiscal support, and focussed on the usual sectors (notably infrastructure). Household spending is also likely to pick up as the savings rate returns to pre-pandemic levels. However, structural headwinds are building as China's economy reaches the limits of its investment-led growth model. Demographics are also deteriorating faster than many had anticipated. This means that any cyclical recovery will quickly hit a ceiling of lower potential growth. Accordingly, in contrast to the consensus, we expect the recovery to fizzle out by the second half of the year and for growth to return to a weaker track in 2025 and beyond.

AI enthusiasm will continue to build. We believe that AI has the potential to drive a significant increase in productivity growth – but that it will take several years for infrastructure and processes to adapt to this new technology. Most of the associated boost to GDP growth is therefore likely to arrive in the 2030s rather than this decade. Nonetheless, optimism about AI’s potential is likely to continue to build next year. Moreover, even if the benefits of AI will take time to diffuse through economies, history suggests that investors will seek to crystallise these benefits upfront. We think AI optimism will continue to boost equity prices in 2024, especially in the US, helping the S&P 500 deliver another year of double-digit returns.

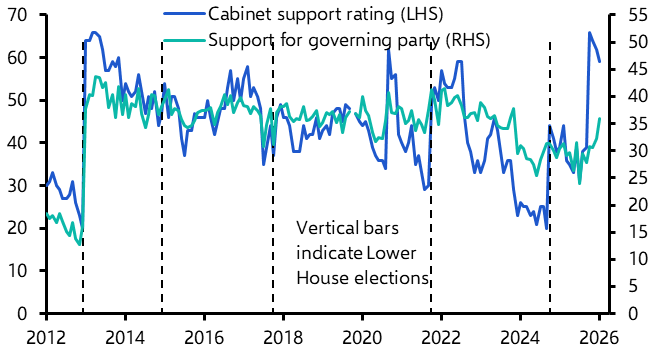

Elections in focus. Finally, it’s being billed as the biggest year for elections in history, with voters from Indonesia to India to the US – and probably the UK – going to the polls over 2024. Although elections dominate news cycles – and are sources of potential short-term volatility in financial markets – their ability to have sustained influence over the trajectory of economies tends to be overstated, not least because the effect of most policy shifts is uncertain and often overwhelmed by other factors outside the control of government.

That being said, the sureties of 1990s thinking, when there was broad consensus around pro-market, pro-globalisation policies, have given way to an era of greater uncertainty. This is most clearly reflected in the breakdown of US-China relations, which is at the heart of the fracturing of the global economy. The outcome of next year’s presidential election in America will not reverse US-China fracturing, but it will shape the form it takes. Under the Biden administration, fracturing has broadened out to include areas such as technology transfers, financial flows and semi-conductors. A Trump victory could see a return to a narrower form of fracturing focussed principally on trade. Moreover, there is a risk that the US adopts a more isolationist approach under Trump that strains relations with Europe. That in turn could weaken the current US-Europe alliance that underpins the relative size and resilience of the US-bloc. Fracturing is here to stay – but the outcome of elections in 2024 will have a significant effect on how it develops.