Investor nerves in recent weeks have been tested by two opposing inflation concerns. The first is that China is on the cusp of a deflationary spiral that will pull down the rest of the global economy. The second is that resurgent energy prices will lead to a renewed rise in inflation in advanced economies, thus complicating the task facing central banks. Both have been framed in ways that exaggerate risks and gloss over important nuances.

Let’s start with China. A negative consumer price reading in July fuelled panic that the Chinese economy was on the brink of a hard landing whose effects would spill over to other economies. At the time, we pointed out that Chinese consumer inflation is typically subject to swings in the availability of pork, which is the country’s most consumed meat and takes up an outsized chunk of the CPI basket. We advised clients instead to focus on core and services inflation, which are influenced more by the overall balance of demand and supply in the economy and which both edged higher that month.

Fast forward a month, and August’s inflation data showed a rise in both headline and core inflation. At the same time, the near-term macro outlook has improved somewhat. Data for August also revealed a pick-up in activity, driven in large part by a healthy rise in consumer spending. And the step-up in policy support over the past few weeks should help to drive a further improvement in activity over the coming months.

The economy is by no means out of the woods; China’s considerable structural challenges mean that any recovery is likely to be subdued and investors betting that stimulus will return growth rates to previous form will be disappointed. But a middling recovery will be enough to push China’s CPI higher in the coming months, while producer prices, which have been in negative territory for 11 straight months, should turn positive by year-end. In other words, not the deflationary spiral that had markets on edge over summer.

Understanding oil’s inflation threat

A very different flavour of inflation fear has dogged developed economies in recent weeks, as oil prices have risen well above $90 and the natural gas market has been rocked by news of industrial action at Chevron’s facilities in Australia.

As with a Chinese deflationary spiral, the idea that higher oil prices are an inflationary threat in advanced economies makes for good headlines but is easy to overstate.

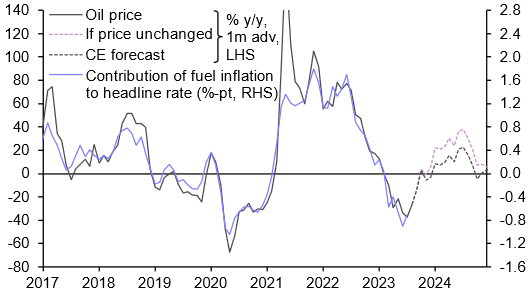

As Chart 1 shows, if Brent crude prices stay at their current level of around $95pb, energy will actually be a drag on headline inflation in developed markets through to the end of the year. Things get more complicated by early 2024, when oil is likely to make a positive contribution to headline inflation. But this is likely to be overwhelmed by other disinflationary forces.

|

Chart 1: Oil & Fuel Contribution to Average Headline Inflation Rate in Major DMs |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Accordingly, on the basis of our forecast that oil prices will nudge down to $85pb by end-23, we expect average inflation in advanced economies to decline to around 3.3% by the end of this year from 4.2% in July, and to 2.5% by mid-2024. (See Chart 2.) What’s more, headline inflation continues to fall even if we assume Brent crude stays at its current level of around $95pb. (See the pink line in chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Average Headline CPI Inflation in Major DMs (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Look below the headline

Rather than fixate on crude prices, investors should again be watching the behaviour of core inflation. Crucially, we expect it to fall steadily throughout the next year as pandemic-related distortions wash through and the effects of monetary tightening start to bite. (See Chart 3.) Admittedly, higher-for-longer oil prices could bleed into core inflation through so-called second round effects as firms pass on higher energy costs to consumers. But this is a much greater threat when the economic backdrop is strong. Given that we expect most advanced economies to slip into mild recessions over the next six months, broader disinflationary forces are likely to dominate.

|

Chart 3: Average Core CPI Inflation in Major DMs (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Don’t expect central bank rhetoric to reflect much of this. They’ve been scarred by the surge in inflation over the past two years so will continue to talk a hawkish game. The Bank of England is likely to follow in the footsteps of the European Central Bank (ECB) and lift interest rates by a further 25bps to 5.5% at its policy meeting this week. And while we expect the Federal Reserve to leave interest rates unchanged when it meets on Wednesday, the accompanying statement is likely to send a strong signal to markets on the need to see the job through.

But this is exactly what one should expect from central banks at this stage of the cycle – the last thing that policymakers want to do is to dilute the effect of prior tightening by sending mixed messages that lead to a loosening of financial conditions. In practice, we suspect that by the end of this week the Fed, ECB and Bank of England will all have reached the peak of their tightening cycles.

In each case, the next move in rates is likely to be down – although the first move in the US is unlikely to come until early next year, with policymakers in the euro-zone and UK not cutting until they are into the second half of 2024. That leaves the Bank of Japan as the outlier among the world’s major central banks for not having raised interest rates. As we set out in our preview of the Bank of Japan’s upcoming policy meeting, that could be about to change.

In case you missed it

In this in-depth assessment of the outlook for EM equities, Senior Markets Economist Tom Mathews explains why we think those in Asia will outperform their EMEA and LatAm-listed peers.

Deputy Chief Markets Economist Jonas Goltermann assessed the outlook for the yen and renminbi in light of high-profile Japanese and Chinese efforts to prop up their currencies.

In light of last week’s news of an EU probe into Chinese electric vehicle imports, this July report outlined Europe’s options, including why a repeat of efforts seen in the 1980s to keep out Japanese cars is unlikely. Listen to this week’s episode of the Weekly Briefing podcast for more on this.