When Europe features prominently in client questions it is not normally a good sign. The past few days have been no exception.

The immediate concern is France, where the government of Michel Barnier was toppled last week after failed efforts to push through a combination of tax increases and spending cuts aimed at putting the public finances on a more stable footing. The political crisis in France is emblematic of the core – and interrelated – challenges facing Europe:

Problem #1: the absence of growth

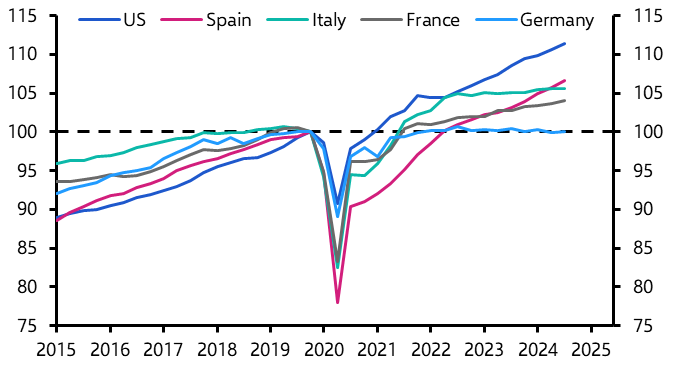

The first, and most critical, problem is that growth has been anaemic across the region’s major economies. Germany has been its worst performer in recent years; its economy is the same size today as it was in the fourth quarter of 2019. In other words, it has had five years of lost growth. But the rest of the region has not fared much better. France’s economy is only 4.1% larger than it was in the final quarter of 2019, while Italy’s is only 5.6% larger. (See Chart 1.) And while Spain’s GDP has increased by 6.6% since then, this has been helped greatly by an influx of immigration that has meant that GDP per head has increased by just 2.9% over the same period. In contrast, the US economy has grown by 11.4%.

|

Chart 1: Real GDP (Q4 2019 = 100) |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

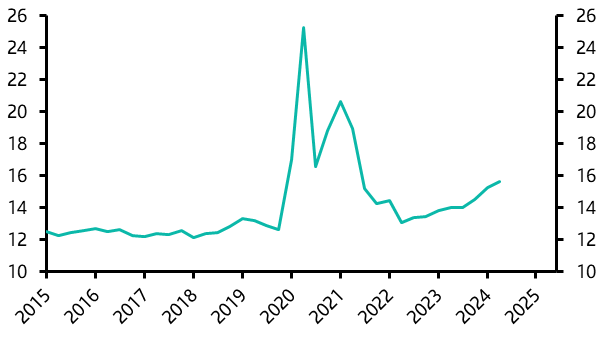

Europe’s relative underperformance has been due in part to the effects of the energy crisis that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This led to a deterioration in the region’s terms of trade that manifested itself in a large squeeze in real incomes and loss of competitiveness of energy-intensive industries. European households have also become more reluctant to spend. The household saving rate in Europe is now three percentage points higher than it was before the pandemic and, while it is difficult to compare across regions, it is striking that the savings rate in the US is now lower than it was in 2019. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Euro-zone Household Savings Rate (% of disposable income) |

|

|

| Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

But the weakness of economic growth in Europe is also structural. There are several elements to this. In France, key issues include labour and planning regulations that stifle competition and innovation, along with a very high tax burden. Core parts of Germany’s manufacturing base – most notably its metals, chemicals and auto industries – are facing structural headwinds. Poor demographics are also playing a role. But Europe more generally lacks the dynamism and entrepreneurial spirit of the US. The whole ecosystem for start-ups is poor and regulation makes it harder to adopt new productivity-enhancing technologies. It is perhaps no surprise that the major disruptive and innovative firms of the past two decades have come from the US and China rather than from the euro-zone. The result is that productivity growth – which is the key determinant of economic growth over the long run – is substantially lower, averaging 0.3% a year over the past decade compared to 1.6% a year in the US. (The UK, incidentally, is decidedly European in this regard.)

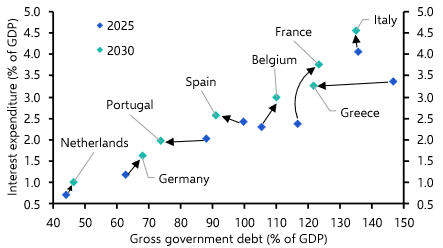

Problem #2: Fiscal imbalances

Europe’s second big challenge is one of fiscal imbalances. The need to rein in a budget deficit that is now running at around 6% of GDP lies at the root of the current political crisis in France. Weak growth makes the job much harder. Economic growth generates tax revenues that make it easier for governments to finance spending, service debt and, where necessary, bring down budget deficits. The corollary is that a lack of economic growth tends to reveal all manner of fiscal problems. This is France today, though a combination of low growth and high debt mean that Italy’s public finances are also in a precarious position.

In complete contrast, Germany’s problem is excessively tight fiscal policy. Its so-called “debt brake” significantly reduces the scope for deficit spending even though the German public debt burden is low. With a stagnant economy, Germany would benefit from looser fiscal policy – and since this would almost certainly suck in imports from other countries, this would help support growth (and thus fiscal consolidation) in France and Italy. It now looks likely that elections scheduled for March next year will result in a government that takes steps to relax the debt brake. This would represent a step in the right direction, but we suspect the changes will be relatively modest.

Problem #3: political intransigence

This brings me to the third problem facing Europe: political intransigence. Europe’s challenges are significant, but they are not insurmountable. It would be possible to reinvigorate growth through a package of structural reforms. (Implementing some of the recommendations from Mario Draghi’s recent report on boosting the region’s competitiveness would be a good place to start.) A commitment to fiscal rectitude in France and Italy coupled with fiscal relaxation in Germany would ease concerns over debt sustainability and contribute to a more balanced European economy. These reforms could be undertaken by national governments, but could also be coordinated through Brussels. Better still, they could be accompanied by more fundamental steps to deepen fiscal union through more joint EU borrowing, as well as banking and capital market union.

But diagnosing the solutions to Europe’s problems has never been the issue. Instead, the challenge has been to build a political consensus that favours introducing the unpopular, but necessary, measures that address the region’s challenges. Instead, these challenges go unaddressed and the region’s problems deepen over time. This provides fertile ground for populists.

None of this is to suggest that a crisis in Europe is inevitable. France is not the new Greece. The European Cental Bank now has an expanded toolkit that allows it to stand behind national sovereign bond markets. The region is likely to continue its tradition of muddling through. But the situation today is different from the earlier crisis insofar as Europe’s most acute problems are no longer concentrated in smaller economies like Greece. Instead, it is Europe’s two most important economies that are struggling. Without reform in France and Germany, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that Europe’s future is one of very low growth, continuing concerns about fiscal sustainability and a dwindling sense of standing in a world increasingly characterised by a superpower rivalry between the US and China.

In case you missed it:

- Paul Ashworth argues that President-elect Trump won’t get the additional deficit-financed tax cuts that he may he want.

- Stephen Brown counts the cost of potential immigration curbs on the US economy.

- Joe Maher makes the case for another upward leg in the gold price.