Ernest Hemingway’s line about bankruptcy happening “gradually, then suddenly” can apply to the geopolitical mood too. The head-spinning recent turn of events around Trump and Putin, the war in Ukraine and the future of European security has seen long-simmering fears about a reorientation of US foreign policy boil over, fuelling talk that it is ending the trans-Atlantic alliance forged at the dawn of the Cold War.

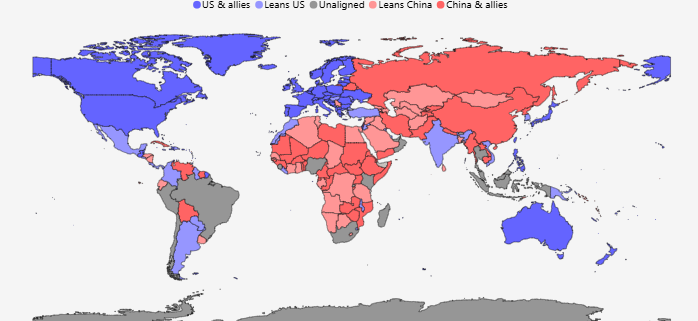

Not so fast. At times like these, it’s important to take a step back and consider what’s actually changed. A framework for thinking is essential. We’ve long held the view that the return of geopolitics as a driver of global macroeconomic outcomes is best seen through the lens of US-China fracturing. This process sees China emerging as a peer competitor to the US, pulling apart – or fracturing – the economic and political relations between Washington and Beijing. This fracturing will not be absolute – we think it is most likely contained to areas of strategic importance. But it will eventually force countries to choose sides. And while our analysis sees Europe in alignment with the US, the events of the past week have challenged this assumption. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Capital Economics’ Classification of Geopolitical Alignment |

|

|

|

Source: Capital Economics |

If the idea of competing US and Chinese economic blocs fails to stand up then an alternative could see Europe splitting from the US to form another economic bloc entirely – a “third superpower”, in Emmanuel Macron’s formulation – around which other liberal democracies might then coalesce. This is possible but unlikely.

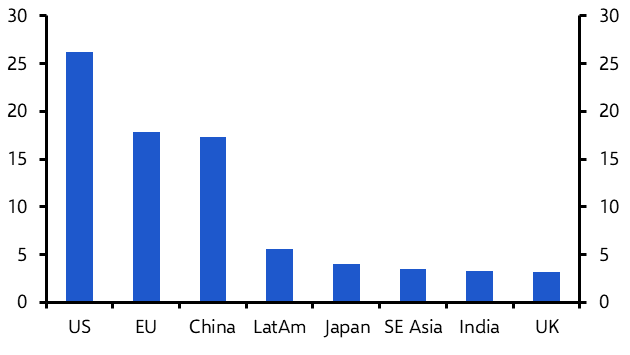

Europe is an important part of the global economy. Collectively, the European Union accounts for about 18% of global GDP when measured at market exchange rates – similar to China’s share (17%) but less than the US (27%). (See Chart 2.) The UK accounts for another 3% of global GDP.

|

Chart 2: Share of Global GDP (%, at market exchange rates) |

|

|

| Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

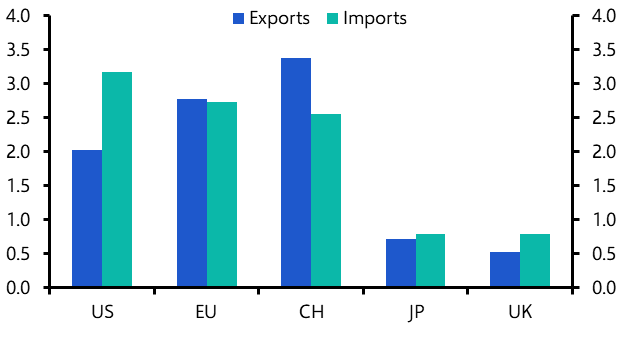

Similarly, while Europe’s population is smaller than China’s, it is a little larger than the US. The EU is also the world’s second largest exporter as well as being its second largest import market. (See Chart 3.) Europe’s struggles with low growth have fed a perception that it has become an economic backwater. This is far from the case.

|

Chart 3: Exports & Imports (US$ trn, 2023) |

|

|

|

Source: LSEG; NB: EU figures exclude intra-EU trade |

But economic heft doesn’t automatically bestow superpower status. Europe may be the only region with an economy to match the US and China, but it is still a collection of sovereign states struggling to speak with one voice. Moreover, Europe does not project its values onto others to the same extent as the US and China. Europe has followed, rather than led, the fracturing process – typically siding with the US (for example, in cutting Huawei from its 5G infrastructure), but also mindful of its links to China. Europe tends to move slowly, seeks both consensus in decision-making and a middle ground rooted in a rules-based global system. These are laudable qualities but they sit awkwardly against the new geopolitical reality and are reasons why a third bloc centred on Europe is a less likely outcome.

An alternative, and perhaps more likely, scenario, is that Europe breaks from the US bloc. This wouldn’t create a third bloc centred around Europe but would instead result in it trying to straddle both sides of the fracturing divide.

There are several ways this could happen. The US itself could decide to sever ties with Europe by raising protectionist barriers, reducing technology transfers and cutting defence and security ties. Alternatively, Europe could push for what Friedrich Merz, who is poised to become Germany’s new Chancellor following this weekend’s elections, has called “strategic independence” from the US.

Amid the heated rhetoric it’s worth pausing to consider what full strategic independence would look like. In a piece earlier this year we argued that it would entail:

- Firms in Europe re-arranging supply chains to supply the US independently from the rest of the world in strategic sectors;

- An effective wall erected between the US and Europe that limits technology usage in sensitive areas and restricts interregional technology flows;

- Europe actively trying to curb its use of dollars and its reliance on the US financial system; and

- The US withdrawing from defence and security groups including NATO, the Five Eyes, the Quad and AUKUS.

While such shifts are no longer unthinkable, there are powerful forces acting against them. Political, cultural, social, economic and security ties between the US and Europe run broad and deep. They have been strained before – notably during the Vietnam and Iraq wars – but Europe and the US havenonetheless remained close allies.

Furthermore, a split on this scale would entail significant economic costs for both sides. This is as true for Washington as it is for Brussels. It is partly the size of the US bloc that gives America an advantage over China in a fracturing world. Without Europe, the share of global GDP accounted for by the US bloc would fall from 70% to 50%. (A dashboard containing all of our fracturing data can be found here.)

But the economic diversity of the US bloc also matters. As things stand, it contains everything from low-cost manufacturers (Vietnam) to high-tech economies (such as Japan and Korea). Europe is responsible for a significant part of this diversity, and the US has come to rely on it as part of its broader push to contain China. For example, ASML, the Dutch company that dominates the production of lithography machines used to create semiconductors, has stopped selling its most advanced machines to China under pressure from Washington. This has limited Beijing’s access to cutting-edge chips used in everything from AI to military technology and demonstrates how America draws strength from the economic diversity of its allies. It is striking that the White House memorandum on America First Investment Policy, issued this weekend, explicitly talks about encouraging investment from US “allies and partners” – and restricting investment from “adversaries”, including China and Russia.

The upshot is that, while the trans-Atlantic alliance will undoubtedly be strained over the coming years, the most likely outcome at the next Inauguration Day is that the US and Europe will still be allies.

So what has changed as a result of the past week’s events? Two things stand out.

First, a deal to end the war in Ukraine could materialise more quickly – and on terms more favourable to Russia – than had been anticipated. Key questions, including on how a ceasefire would be policed and how quickly and on what terms Russia could be brought back into the fold, remain. Our sense is that Europe in particular will remain reluctant to re-engage with Russia and that the broader macroeconomic implications for Europe and the rest of the world of a cessation of fighting will likely be limited.

Secondly, European governments are now under even more intense pressure to increase spending on defence. The macroeconomic context, of course, is that major economies in the region – with the exception of Germany and the Netherlands – are fiscally constrained. This argues for the issuance of bonds that are jointly-backed by all EU countries for the purpose of raising defence expenditure, just as the EU did to fund its €750bn pandemic recovery programme. That may eventually take place but there will be strong opposition from countries such as Hungary and so far Mr Merz has also resisted the idea of additional joint borrowing.

The result is therefore likely to be incremental, rather than revolutionary, changes to European defence spending. At the same time, European leaders have been clear that any credible military backstop for a Russia-Ukraine peace deal would need to be underpinned by the US. So while defence spending in Europe will have to increase, the region’s reliance on the US military umbrella is unlikely to come to an end.

Whether Trump will be receptive remains to be seen – nor is it clear how much European defence spending would need to rise to satisfy the president. But on the big question of geopolitical alignment in a fracturing world, there is still more that unites the US and Europe than divides them.

In case you missed it:

Our initial response to the German election outcome highlights possibilities around the make-up of the next ruling coalition and the likely policy agenda of a Friedrich Merz-led government. Our election Drop-In is at 1000 ET/1500 GMT on Monday – click here to register for the live session or to watch the recording.

Friday’s US Weekly tackled the latest signals on Trump’s tariffs and Musk’s efforts to shrink the federal workforce.

Liam Peach will be walking clients through the latest refresh of our EM Financial Risk Indicators in a Drop-In on Wednesday at 1000 ET/1500 GMT – register here for the 20-minute online briefing.