In August 2015, a botched change to the way that Beijing managed the renminbi triggered global panic amid worries that a hard landing in China would take the world economy down with it. Crisis was averted, thanks to yet another round of stimulus and a tightening of capital controls. But fears that problems in China could derail the global economy never really went away as evidence gathered that the country’s investment-driven growth model was running out of steam.

Eight years later, fears about China’s threat to the global economy are bubbling up again following a swathe of weak activity data, a larger-than-expected cut to policy rates, a teetering property developer and signs of strain in the tangled web of shadow financing. Joe Biden has weighed in, calling the economy a “ticking time bomb”.

Should the rest of the world be worried?

Getting things straight

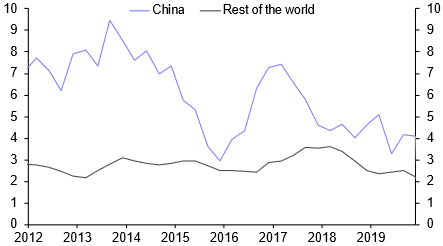

There are three things that analysts tend to get wrong when discussing links between China and the rest of the world. The first is that, while China is clearly a hugely important part of the world economy, its influence on the global cycle is often overstated. The relationship between growth in China and growth in the rest of the world is not particularly strong. This is important context when considering some of the more breathless headlines of recent days.

|

Chart 1: China and Rest of World GDP (%y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics; *China is CAP measure |

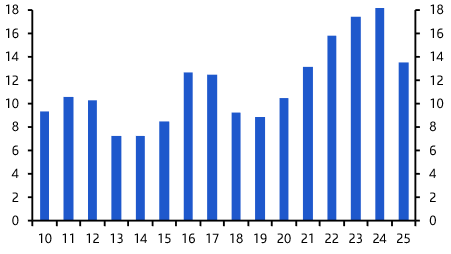

The second is that, despite China’s size, it has not been a source of significant net demand for other economies. Admittedly, when measured as a share of global GDP, China’s current account surplus has fallen back from the highs seen in 2021. But the fact that it remains positive means that China is still a net drain on demand at a global level. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: China Current Account Surplus (% of global GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: Capital Economics |

Finally, there is often a disconnect between the macro and the market spillovers from China to the rest of the world. While the macro linkages are often overstated, the fact remains that concerns about the outlook for China have caused periodic bouts of market turbulence. This is both because investors perceive China to be an important source of global demand, but also because China accounts for a large share of the revenues of major corporations such as Apple and Tesla. Accordingly, it’s possible that weakness in China could have little bearing on other major economies, but still cause significant dislocation in global financial markets.

So having set the record straight, should the rest of the world be concerned? At the risk of stating the obvious, it depends on the scale and duration of the downturn in China, and what is causing it.

Risks greatest in EMs

The immediate concern surrounds the property sector in the wake of the problems at the developer Country Garden. While China’s property sector is facing a prolonged and structural downturn, our base case is that a combination of targeted support and, where necessary, state backstops, will prevent problems at individual developers from infecting the wider financial system. In fact, it’s likely that problems in the property sector will encourage broader policy support for the rest of the economy.

Accordingly, we suspect that looser policy will help to put a floor under China’s economic downturn over the second half of this year. So while the near-term outlook is still challenging, China may not be the “ticking time bomb” that President Biden suggests. Indeed, since the weakness of Chinese domestic demand has exacerbated excess industrial capacity caused by the normalisation of goods demand elsewhere, it may be beneficial for the rest of the world in that it contributes to global goods disinflation.

There are two main risks to this view. The first is that the government misreads the problems in the property sector and fails to put an adequate financial firewall around them. The second is that policy support for the broader economy is too slow in coming or timid in nature. Both would threaten a deeper downturn in China, with the property and construction sectors at its core.

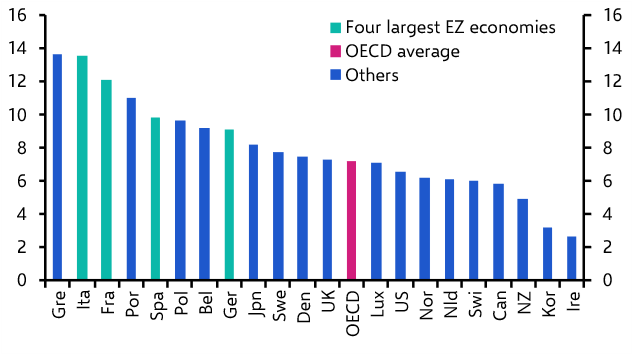

If this were to happen, the demand spillovers would be bigger for emerging than developed economies, but are again easy to exaggerate. Parts of Africa, Latin America and Australia are exposed through their exports of metals (see Chart 3), but there is otherwise little trade exposure to China’s construction sector. A more general fall in commodity prices would hurt export revenues, but also benefit net consumers in a time of high global inflation. Meanwhile, cross-border investments with China are small, and foreign bank claims on its private sector are less than 1% of GDP. It would require a monumental collapse in China to meaningfully alter the near-term outlook for the US economy.

|

Chart 3: Commodity Exports to China (% of GDP, 2022) |

|

|

|

Sources: OECD, Intracen, Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

A shift in the global policy dynamic

The risks to advanced economies from a long-term structural slowdown in China are also misunderstood. We have argued for some time that China’s growth rate will slow to 2% a year by the end of this decade. But while this will arithmetically pull down global GDP growth over the next couple of decades, and will be a major headwind to EM commodity producers such as Brazil, Chile and Zambia, we do not think it will have a significant bearing on the long-term growth outlook for the US or Europe.

However, weaker growth in China will alter the geo-economic policy dynamic. The era in which the US and China embraced globalisation as a win-win has been consigned to history’s dustbin. Its replacement is a more hostile environment in which the global economy is fracturing into rival US and China-led blocs.

In our work on economic fracturing – or geo-economic fragmentation, in the IMF’s language – we have shown the various ways in which the global exchange of goods, services, capital, people and ideas may be re-routed. One key insight is that the impact on multinational corporations headquartered in advanced economies and trading in those sectors most affected by fracturing is likely to be significantly greater than the impact on long-run GDP growth in those economies. Emerging economies aligned to China will also suffer more in an age of increased geopolitical friction and heightened economic uncertainty.

A similar story plays out as China slows. Despite alarming headlines about the threat to the world economy in aggregate, it would take a full-on Chinese hard landing to really degrade the global outlook. While vulnerabilities in China’s economy are mounting, this isn’t our base case. Instead, the effects of a slowing China are a greater problem for those global firms and commodities producers that do most business with it.

Investor fears about China are less visceral than they were eight summers ago, in part because this latest bout of bad news lacks the surprise element of 2015’s devaluation. But worries about China’s impact on the global economy are continuing to dog markets, showing how little has been learned in those intervening years.

Given how long we’ll be living with China’s economic struggles, investors will have plenty of time to get up to speed.

In case you missed it:

This week’s podcast episode includes more on China, as well as discussion about the bond market sell-off, Powell’s upcoming appearance at Jackson Hole and more. Listen to it here.

There will be lots of talk about a BRICS currency at the group’s Johannesburg summit this coming week. Mark Williams and Shilan Shah explained why it won’t work in this May report.

James Reilly from our Markets team looked at why the tech stock rally has stumbled and whether outperformance will return.