The Weekly Briefing:

The bond market disconnect, a fiscal policy outlook and an exclusive China briefing

A Capital Economics podcast

18th August, 2023

Government bond yields have been hitting multi-year highs even though data show inflation in retreat and central bankers are preparing to down tools – if they haven’t already. Why the disconnect? Group Chief Economist Neil Shearing talks to David Wilder about what’s been happening in the bond market, whether this is why some EMs have been struggling, and what Jerome Powell might say at Jackson Hole this week.

Plus, Global Economist Ariane Curtis has just completed work on the outlook for fiscal policy in developed markets. She talks to Senior Global Economist Simon MacAdam about why policy is likely to continue supporting growth and how this complicates the task of central banks to get inflation under control.

And, amid growing fears about China’s economic and financial risks, the team held an online briefing to give clients a chance to ask about everything from where the renminbi is going to local government debt to whether China is turning into Japan. Listen to an exclusive clip from that briefing with Neil, China Economics head Julian Evans-Pritchard and Senior Global Markets Economist Thomas Mathews.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 18th of August and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up: why fiscal deficits aren't going anywhere and the latest on China's economic problems. But first happy to say I'm joined once again by Group Chief Economist Neil Shearing. Hi there, Neil.

Neil Shearing

Hi there David.

David Wilder

We’ve got to start with the bond market don't we. Yields at multi-year highs, even though inflation is in retreat and tightening cycles look like they've basically done – maybe one more hike from some of the banks – talk about what's been going on what and we think is going to be happening?

Neil Shearing

Yes, yet again, events in the bond markets dominating over the past week with the 10 year US Treasury now up to 16-year high, as you say. I think there are two points to make and indeed, we made this point in a piece we published over the past week. The first is that if you look at what's been happening between the spread between nominal bond yields, and inflation-protected securities, that spread’s been pretty flat. So this is mainly about real bond yields going up. And the second point is that if you look at what the markets anticipating in terms of the peak for US interest rates, in particular, that's not really changed. So I think there are two important points to draw out from this: the rise in yields over the past week or so is not because the bond market is suddenly thinking that the Fed is going to have to raise rates a lot further in the short term. It's more about the fact that it believes that rates are going to have to stay higher for longer and it believes rates will have to stay higher for longer, not because inflation is going to be higher, but because the real economy is stronger, and therefore real rates are going to have to be higher accordingly.

David Wilder

We've spent a lot of time thinking about recession risk through this prism of tightening credit conditions. What does this surge in yields mean, then? Is this is this where we are? I know we've also got US mortgage rates above 7%. What does the US look like with the 10 year yield at four and a half percent?

Neil Shearing

Well, the housing market looks pretty challenging in terms of affordability – I don't think it’s necessarily on the cusp of a crisis because of the way that the mortgage market operates and the fact that many households have locked in low rates for long periods of time. But on an affordability basis, it looks pretty challenging and I suspect activity there will be low for a long time to come. I think more fundamentally, as we've talked about before, it just takes time for the transmission of monetary policy to feed through to the real economy. We still think that only about half, perhaps just a bit over half, of the effects of monetary tightening have been felt in the real economy. And when you look at things like the Senior Loan Officer Survey in the US and other surveys of credit conditions and bank lending intentions elsewhere, it looks like banks are going to be tightening lending further over the coming months and quarters. So I think there's still quite a considerable amount of monetary tightening yet to be felt in the real economy and I suspect that's going to start to come through over the final part of this year.

David Wilder

Let's talk a bit more than about the outlook for yields because there's an idea during the rounds that, you know, this post-Global Financial Crisis rate environment was an anomaly – this world of 0% rates – and that yields are returning to a sort of pre-GFC 4% world. What do you say to the idea that yields are going to settle around here, or even go a bit higher?

Neil Shearing

Well, I think in some senses, that's right, in some sense it's wrong. The bit that's right is that that period of extremely low yields, and even negative yields, post-GFC, I think, was an anomaly. And it was about the extremely loose start to monetary policy that was required in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis to help banks and firms and households repair balance sheets. And we see that time and again through financial crises. And I think we're now through that period. So we're not going back to a period of ultra-low yields and interest rates anytime soon. On the other hand, the question is whether we anticipate that the new normal for 10-year yields is kind of four and a half or 5%, or perhaps even higher? Equally, I have difficulty believing that that will be the case either. I suspect that the neutral real interest rate has increased over the past few years, it will be higher than it was in the wake of the financial crisis nor do I think that we're going to need kind of 5-6% yields to really squeeze inflation out of the system for the next decade. And now we'll be looking at all of this in a major piece of work looking at so called R* or the equilibrium real rate of interest that we'll be publishing at the start of October,

David Wilder

Still, looking at the near term, a pretty tricky environment, isn't it? the coming week I guess the big event is Jackson Hole, the big central bank meeting in Wyoming run by the Fed. At last year's, Jerome Powell reportedly had this long wonkish speech prepared which he ditched at the last minute in favour of that short and sharp hawkish statement about getting inflation under control. Given all this happened over the last 12 months and the outlook for the coming weeks, how do you think Powell is going to play it?

Neil Shearing

Well I suspect you won't see the same fireworks that we had last year. If you think back to 12 months ago, we had a situation where inflation both on the headline rate, but also on the core rate was rising and rising sharply, the labour market was extremely tight, wage inflation was high and rising and getting to an uncomfortable place for the Fed. So I think at that point, we got to a place where the Fed really had to step in, Powell had to step in, reset expectations and be clear, with the bond market in particular, about their commitment to getting inflation under control. Fast forward to today and inflation, by the looks of things, is more under control, it's falling, and it's falling a bit more quickly than many in the market anticipated in the US. And yet the US economy is not yet showing any signs of falling into recession. So the Fed’s in a bit of a sweet spot with inflation falling and the economy not yet falling over. So I think there's less need for the kind of dramatic fireworks from Powell. So I'd be surprised if we got any kind of explosive statements from him. So he's not going to be saying “Mission Accomplished” on inflation, he’s not going to be giving any signs that rates are about to be cut or any indication of policy easing but nor is he going to be sending a message that they've got lots more work to do. The big question now is what will happen at September's FOMC meeting. Likewise, I don't suspect he's going to give much away on that front either given that the debate amongst the FOMC appears to be pretty finely balanced. We think that when it comes to September's FOMC meeting, the Fed will remain on hold. It's done with its tightening, we think, and therefore, by the time we get to the end of this year, we'll start to see a drop back in yields as markets turn their attention to the prospect of policy loosening in 2024.

David Wilder

Let's step back from developed markets. We're talking about some of the spillover effects of what's been happening in the bond market. We're talking after a week in which the PBOC has been trying to stop the renminbi slide. It started with the Argentine peso and the Russian ruble plunging and rates in both countries have been jacked up. If this was 1998, or 2013 we'd be calling this an EM crisis. But we're not this time. What's changed? And what's the outlook here?

Neil Shearing

Well, I think there's a tendency isn't there to link what's happening in emerging economies to the moves in bond yields that we've seen over the past week or so with yields now, as I said, at the start 16-year high. That clearly puts pressure on emerging economies and currencies of emerging economies. However, I think it's more accurate to say that what's happened in China and in Argentina, and indeed, in Russia, is more idiosyncratic. It’s more linked to events in each of those economies rather than a global EM phenomenon. Indeed, if you look at the kind of traditional bellwethers of EM risk appetite like the Mexican peso, they've come under a bit of pressure but they're certainly not collapsing. So what is going on in those economies? Well, in China it's all about the property sector, which I know we'll come on to later in the podcast, in Argentina it's about a primary election which is a dry run for the general election later this year in which a right-wing populist did well and has raised concerns about the direction of policymaking and in Russia, it’s about the erosion of the current account surplus because of loose domestic policy. Indeed, that's something that our Senior Economist EM Liam Peach flagged as a risk earlier this year. Those risks seem to be coming to fruition and it's manifesting itself in downward pressure on the ruble. So I think the drivers are more idiosyncratic and country-specific than related to the rise in US yields over the past week or so.

David Wilder

That was Neil Shearing on another tumultuous week in bond markets. We'll be covering Powell’s appearance at Jackson Hole this coming week. So watch out for that and also look out for that project on the long term outlook for inflation and interest rates and what all that means for markets – should be coming in October. Now, the story this past week has been China's economy. Our China team was the only forecasters to call Tuesday's policy rate cuts and were online later in the week on a Drop-In, which is one of our regular short form webinars, to brief clients all about the size and scope of Chinese economic and financial risks. Neil led the briefing with China Head Julian Evans-Pritchard, Tom Matthews from our Markets team and Chief Commodities Economist Caroline Bain. In this clip, you'll hear our views on recession risk, the renminbi outlook and more. But it starts with Julian bringing clients up to speed on just what's gone wrong for China.

Julian Evans-Pritchard

The Chinese economy has lost a great deal of momentum over the past last few months. We already know from the Q2 data that growth was pretty weak. And then the latest data that we got this week suggests that actually growth slowed even further in July and on most indicators, in month-on-month terms at least, barely grew at all. So at the moment activity seems fairly stagnant. The inflation data have obviously raised a lot of concerns because we had the first negative reading for consumer price inflation for a while. While I don't think seems isn't quite as bad as the inflation data suggest – if you look at core inflation, services inflation, it's still positive and actually picked up slightly in July – clearly, inflation is very low. There's some cyclical weakness in the economy, the labour market is softening again. And on top of all of those sort of backward-looking indicators, there's been some concerning developments for the near-term outlook, particularly the developments surrounding Country Garden, which I think are going to further undermine the confidence of households and creditors in the housing market. And we've already seen in recent weeks signs of renewed weakness in the property market even before that Country Garden news. And then more recently, the trust company Zhongzhi which was having problems with missed interest payments last week, and today, confirmed it’s in a liquidity crisis, and is now seeking a restructuring. So further signs that some of the losses in the property sector are spilling over into wider financial instability to some degree. And I think that's going to be something that weighs on sentiment even further over the coming weeks. And all of that is likely to keep activity pretty depressed, and at least in the very near term.

Neil Shearing

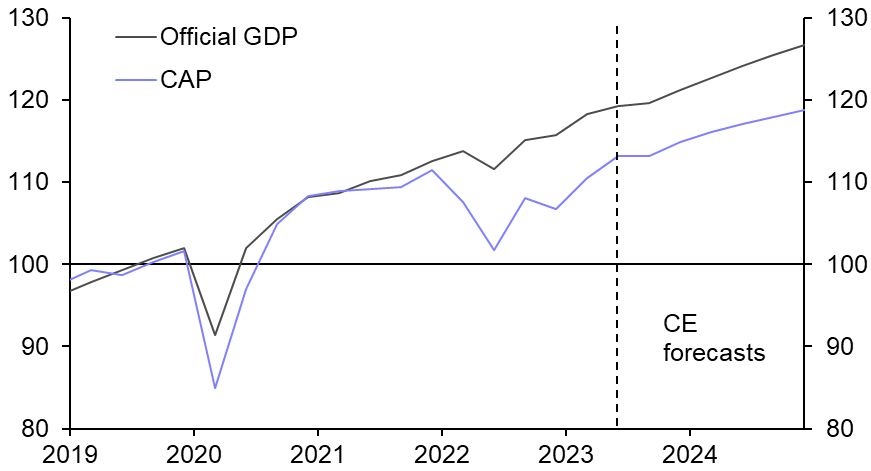

Okay, so put some numbers on it. We're just thinking about tweaking our forecast. So what are we looking at for the back end of the this year and then 2024. I should say, actually, when we think about Chinese economic growth, we look at our own measure, though, which the China Activity Proxy primarily which we build from the bottom up to give us a more accurate read. What's the latest readings on the China Activity Proxy and where do we think it will go over the kind of coming quarters in terms of numbers and then 2024.

Julian Evans-Pritchard

So for some context, our China Activity Proxy was a lot weaker than the official GDP figures last year, it actually had an outright contraction. Once the economy reopened, there was a fairly strong recovery at the start of the year but that's now fizzled out significantly. And, in fact, on our June reading, the economy actually tipped into contraction again. We're still finalising the July numbers but it looks like July is going to be pretty weak as well. Now, I don't think that that's necessarily the start of a recession in China. Clearly the risk of a recession is rising, but we are seeing some policy support now being rolled out. But clearly, the degree of policy support combined with all the headwinds that I mentioned earlier, suggest that growth is going to be pretty weak in the near term. So, we now expect growth over the second half of the year to only average 3% annualised in q-on-q terms, so pretty weak by historic standards. And that's still assumes that policy support continues to be stepped up. If we don't get greater policy support soon, then the outcome could be even weaker than that.

Neil Shearing

Yeah, let's dig into the issue of policy support, because we've had lots of questions about what policy support might come, what form it might take, how large it might be. Also, a really good question about the calculation going on in the government between the need to provide some policy support, but also how they're thinking about the trade off potentially when it comes to monetary policy and the weaker renminbi. So talk us through the calculation that policymakers are making, but also the type of policy support we might expect over the coming months and just how large it might be?

Julian Evans-Pritchard

Well, I think policymakers are in a tough place, partly because some of their usual tools are not really working at the moment. So, typically, in the past, China or in particular the central bank has been able to pump up credit growth simply by giving the banks higher loan targets and cutting the RRR giving them more liquidity and the banks would duly step up their lending. And typically, most of the easing has not taken place through the interest rate channel. Interest rate cuts have usually just been small, used as a signalling tools with quantitive measures doing the bulk of the heavy lifting and monetary easing in previous cycles. The problem at the moment is loan demand is simply too weak. So even though you increase those loan targets, do the RRR cuts, that's not really feeding through to increased lending. To boost loan demand, the central bank would need to cut interest rates far more aggressively than what we've seen in the past. Now it took a very small step in that direction this week when it did a 15 basis point cut to the MLF rate instead of the usual 10 basis point cuts that it usually does. But obviously 15 basis points is still not going to cut it at all in terms of really reviving loan growth. So if they're serious about reviving credit demand, then they need to move in much larger increments. The problem with doing that, of course, is that will put a lot more downward pressure on the exchange rate because at the moment the market is not anticipating very substantial interest rate cuts and I think that is a big concern for them. And so although we've pencilled in a few more cuts this year, we're still expecting them to be fairly modest because I don't think they want to trigger a huge amount of exchange rate instability, although to some extent large rate cuts and major devaluation in the renminbi would probably be the positive for the economy. But I don't think that's the route they will take. I think they'd rather go down the route of greater fiscal support. Now, there's a great deal of sort of debate going on in China about what form that should take, should it be financed by local government, should it be financed by the central government, or possibly through quasi-fiscal means, policy banks, or even PBOC funding through some of its lending facilities. And there's also a debate about what form the spending should take. There's some people who are pushing for direct handouts to households. But the general consensus in the government at the moment seems to be that actually, if they give money to households, households probably will just save a lot of it. And so a lot of it won't feed through in terms of greater spending and tighten the labour market. So I think overall, they're probably going to focus on their traditional method of doing infrastructure spending, maybe with a tilt towards new infrastructure, renewables, that kind of thing. But I think that's still likely to be their backup option. The other area where we could see more is on housing policy. So far, they've largely left it up to individual cities and governments to determine how much easing to do. But if they get seriously worried about the health of the housing market, they could take more aggressive nationwide action. So, for example, at the moment, the minimum downpayment requirements nationwide is 20%. That was last changed in 2008. I think it would send a pretty strong signal if they were to reduce that. So they still have some tools at their disposal. It's just a question of the political willingness to use those tools. So far, we've seen kind of an underwhelming response.

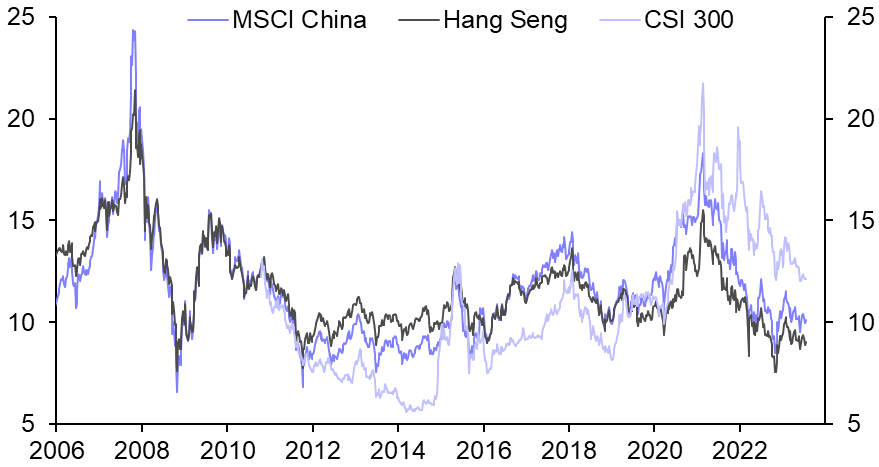

Neil Shearing

So underwhelming response so far, bit more monetary stimulus to come in the form of rate cuts, but unlikely to really move the dial, we should be thinking more about fiscal support, and largely skewed towards infrastructure potentially. Tom, let me turn to you. Tom Matthews from our Markets team. We've had several questions, not unsurprisingly about the currency. And in particular, whether there's a particular line in the sand that the government's likely to try and defend, that the authorities will defend how low is the renminbi going to have to go before the authorities really step up. Indeed, have they already stepped up given what's been happening at some of the state banks, some of the purchases made by the state banks over the past week or so? Are they actually already intervening in a kind of quasi fashion anyway?

Thomas Mathews

Yeah, I mean, I think you're right to say that, obviously, there's an extent to which they have stepped up either directly or indirectly. And, you know, obviously, these things are cloaked in a little bit of mystery, we don't totally know what's going on. But you look at the price action, as they've got closer to that sort of critical levels at 7.3 against the US dollar and so on. And it does seem pretty clear that somebody is doing something to stop the renminbi from weakening too quickly through that. I suppose what remains to be the open question is, is it the speed of depreciation or the level of the currency that they're particularly worried about? And will we just continue to see a sort of gradual weakening of the currency perhaps through that critical level or not. Obviously, that that's challenging one to say – they're not necessarily the most open communicators – but we could see the renminbi gradually weaken through some of those key levels if they're happy to weaken the currency. And, as Julian mentioned earlier, I think that might be one of the key channels to which they could actually support the economy. But no doubt at the same time, there'll be a bit worried that, you know, once you go through those key levels, investors might take it as a signal that you're abandoning pegs or that they’re sort of switching attitude on the currency. Obviously, they've had problems with this sort of thing in the past, and no doubt either way I think there'll be there'll be pretty nervous about it.

Neil Shearing

Yeah I think that's right. There's the there's political implications on that at the level of the exchange rate that kind of says a political signal, particularly if it increased potential problems, we could be choices probably get below particular levels, so that at a kind of political and geopolitical level, but from a macro financial stability perspective, I think it's much more about the speed of the move. And it will be more concerned about rather than defending necessarily a particular level, Julian, I'm conscious of time, there's lots of really good questions to get through. Three, in particular, one on the extent to which actually, the questioner talked about de-risking, but we've talked about fracturing, to the extent to which US-China fracturing might we playing a role in some of the weakness that we've seen in China. Second there whether China is going down the same path as Japan, deflation periods, very low economic growth, balance sheet problems, and then related those balance sheet problems, third question, question about the financial health of developers and balance sheets of developers, but also as the government as well for local governments, but also the general government, the central government. So three questions: fracturing, is that played a role, Japan is that the path that China is heading down, and the health of China's balance sheets, both developers but also at a governmental level.

David Wilder

And you can get the full recording, including Julian's answers to those questions, on the Drop In link that's posted on this podcast page. Check out our events page for recordings of Drop Ins past and see our China Economics page for more about the risks of the world's second biggest economy. Now, part of the puzzle to what's been happening in bond markets may be in how governments have been managing fiscal policy coming out of the pandemic, The Economist recently called DM fiscal deficits, “mind bogglingly reckless”, but does that mean governments are going to take action to tackle them? And what does that mean for inflation and interest rates? A new report by global economist Ariane Curtis looks at fiscal policy in a post-pandemic world and she spoke about her findings to Senior Global Economist Simon MacAdam, this past week. Their conversation begins with Ariane explaining how government budgets have been moving since 2020.

Ariane Curtis

Already, we've seen that fiscal policy has tightened relative to 2020. And that’s because as emergency support measures related to the pandemic, and then later energy support measures, primarily in Europe but also to a lesser extent in Japan, have come to an end or are going to roll up soon, we've seen budget deficits narrow across advanced economies quite significantly. We've seen the headline budget deficits narrow by about seven percentage points since 2020 across the major advanced economies. And similarly, we've also seen structural deficits, which are adjusted to account for where economies are in the cycle and primary deficits, which strip out interest expenses, narrow as well. So we have already seen quite a significant tightening relative to 2020. But what we've seen as well is that budget deficits are still higher than what they were before the pandemic. So if we look at the IMF estimate of the G7 structural deficit, it was still at 5.2% of GDP in 2022 and that's compared to only 3.8% which was before the pandemic.

Simon MacAdam

Yeah, right and thinking about where things are going in terms of fiscal policy and what the outlook is. I mean, there are lots of moving parts to consider here, because ordinarily, we're thinking about tax revenue and expenditure. But normally, when we're thinking about expenditure, we're not usually or at least in the last few years haven’t really been thinking about interest expenditure, but that's going to be more prominent feature of the fiscal policy isn't so. So what's, what's the outlook for fiscal policy in advanced economies?

Ariane Curtis

Yeah, so fiscal policy is set to tight somewhat over the coming years. And that's because, as I've said, the emergency support measures have either ended or are going to roll off soon. And governments in those countries, which also had fiscal rules, are going to make efforts to return to these previous targets, we expect because of this budget deficits to generally narrow further in major advanced economies. And that's going to contribute to slower growth as this fiscal policy gets tighter. There's a bit of a difference between headline budget deficits and what we look at, which is primary deficits. And that's, as you mentioned, because of the difference in interest expenditure. So we're going to see a narrowing in both the headline deficit, but also the primary deficit. And that's because, even if we exclude interest expenditures, we are going to see government's spend less over the coming years and tighten their fiscal policy.

Simon MacAdam

I think the thing to think about with the interest expenditure as well is that even though bond yields themselves may be at the peak, and even if you thought they were going to fall as we do – that's, that's our forecast, that bond yields fall by the end of this year to next year – you're still actually over the next couple of years have the interest burden to the public sector actually keep growing, even if yields peak and start coming back down again, because of course, the key thing is about when the government is refinancing, its debt, paying off existing debt and then re-borrowing the money, what you need to be comparing with is the interest rate you're paying now compared to what you were paying when you issued that initial bond many years ago when interest rates were much lower. So consequently, in higher interest expenditure going to be but a sort of a major feature of the headline, as you say that this is why it's so important to distinguish the difference between the headline and the primary budget deficits even more so now than we previously have done in recent years. You’ve painted a big picture there of budget deficits narrowing a little bit in the coming years. But I think amongst major advanced economies, the US is slightly different – we're seeing less sort progress in that regard. Tell us why that why that might be the case.

Ariane Curtis

This really comes down to where actually economies are starting. So the US is starting in a bit of a different place, then, for example, the euro-zone and the UK. And that's really because of the different kind of energy crisis which Europe experienced which wasn't really an issue in the US. So, in the US, the primary deficit already in 2022 is back to around its pre-virus level and that's very different to the case in the euro-zone, for example. But what we're going to see, we think in the US is that the primary deficit is actually not going to narrow much or really, if at all over the next few years. And that’s because even if, accounting for the tighter budget outlined in the debt ceiling deal, the government is still set to increase spending over the coming years. So that really means that fiscal policy in the US is going to be a bit more supportive of growth there than in other countries over the coming years.

Simon MacAdam

I mean, this is all a discussion, quite rightly, deficits are a very important metric for assessing the public finances. But that's dealing with the flow of debt. But what about the actual stock debt? What's happening to public debt ratios in the coming years?

Ariane Curtis

We think that the kind of combination of higher interest payments, weak GDP growth, and the fact that you know, governments in advanced economies are going to be running pretty large primary budget deficits compared to before the pandemic over the coming years, means that debt-to-GDP ratios in most advanced economies are going to rise. So they're going to be higher in five years’ time, for example, than they were before the pandemic. And you know, this is especially true in the US because, as we just mentioned, they're not really going to be narrowing their primary deficit at all over the coming years.

Simon MacAdam

I suppose these elevated levels of public debt ratios is another reason to think that long term interest rates may settle at a higher level than we've been used to in previous years. And it's just worth flagging that we will be discussing this in a lot more detail in a series of in depth reports later in the year, around October time. Now, we've got budget deficits narrowing in the coming years, albeit primary deficit not really moving very much in the US. What does this mean for growth? How does the fiscal policy stance interact with the outlook for real activity?

Ariane Curtis

Because of the narrowing in the deficit in most advanced economies, we do think since this would constitute fiscal policy tightening, it will contribute to slower growth in these advanced economies over the coming years. But really, the kind of big picture is that even taking into account the further improvements and budget balances, the deficits are going to remain larger than they were before the pandemic in most cases, meaning that fiscal policy is still going to be relatively supportive of demand compared to what we were used to seeing before the pandemic. And while the tightening could weigh on growth somewhat. We think it's going to do very little, if really anything at all, to reduce inflation, which will make central banks jobs that much harder over the coming years.

David Wilder

That was Ariane Curtis talking to Simon MacAdam, I'll post her report on the podcast page. Do take a look. It's an eye opener if you're thinking about how quickly inflation is coming down and how tightening cycles are going to play out. But that's it for this week. All our insight is on our website, capitaleconomics.com. But only CE Advance clients get the full access, including economist engagement tools, invites to all our online and in-person events, interactive data and much more. So check out CE Advance. And until next time, goodbye.