Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 26th of January and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, is another global supply shock flowing from the Red Sea. And will China's latest stimulus plans be enough to give a sustained boost to its economy and stock market? But first, Neil Shearing Group Chief Economist is here to give us the lowdown on the big macro market issues for the coming week and it's Fed Week. Yippee! How's it going, Neil?

Neil Shearing

Hi David, how are you doing?

David Wilder

Good.Good. Excited for Fed Week? It's coming on the back of another big upside in the US GDP growth data. That Q4 number, not as strong as Q3, but still pretty impressive. We're days away from that FOMC meeting. How do you think the board will be looking over recent data in terms of deciding when to cut rates?

Neil Shearing

Yeah, sure. The key data over the past week for the US has been the GDP release - not necessarily for the reason that one might assume, I think. Obviously, the headline real GDP growth number was very strong. It cooled a bit from Q4, so down to 3.3 % annualised. That still meant that the US economy grew by 2.5 % in 2023 as a whole, which is remarkable when you think about the degree of rate hikes that we've had over the past 18 months or so. However, I think the most significant part is that we learned that core PCE inflation is running at about 2% quarter-on-quarter annualized in Q4. So the key measure of core inflation that the Fed looks at is now back at the Fed's target. So the economy is strong and lots of people are focused on that. Clearly that's a good news story. But the most important thing I think is that core inflation number now is back at the Fed's target.

David Wilder

So what are you expecting from the messaging from from Powell and others on Wednesday? What do you think they're going to be hinting, if anything, about the timing of a rate cut?

Neil Shearing

That's the big question, isn't it? I don't think they're going to give us a great deal of insight, if I'm being honest. A lot of the speeches, communications over the past month or so pushed back a little on the idea of a rate cut in March and tended to shift things perhaps later into the year, perhaps the May meeting. However, the key rhetoric that we've had from policymakers, not just in the US actually, we've had it from the ECB in the past week too, that they're data dependent. And if they really are data dependent, then a) there's a lot of data to come between now and the FOMC meeting, the next FOMC meeting in March. And b), if you speak to our Chief US Economist, Paul Ashworth, his view and the view of our US team is that most of that data is going to support the disinflation trend. So it's going to come in on the side of the doves as it were. So I think whether they cut in March, whether they cut in May,

I think they're not going to be committing either way. But a March cut, I think, is still in play.

David Wilder

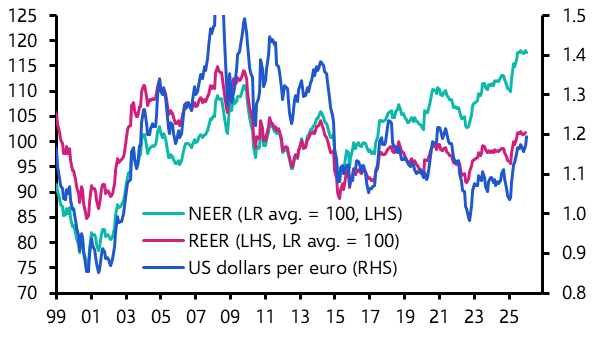

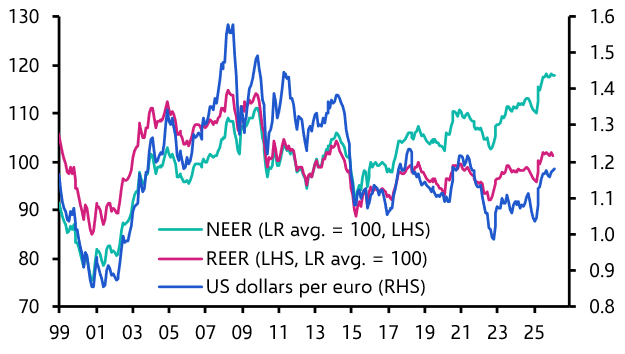

There's a cluster of important central bank meetings going on in recent days and the coming days. I want to talk about that ECB meeting, specifically Christine Lagarde's presser. No move on rates coming out of that meeting as expected, but Lagarde's comments and then a subsequent fall in yields and the euro left our Europe team wondering if that first rate cut could come later than markets. Our pricing, can you talk about what happened?

Neil Shearing

Yes, our Europe team have been busy unpacking the messages from the ECB. The statement itself was pretty much unchanged. But I think the language that Lagarde used in the press conference continued to push back on this idea of a rate cut much before the summer. I think the words that Lagarde used were something to the effect of there was consensus on the Governing Council that it was too early to talk about rate cuts now. Also, lots of talk and discussion in the subsequent press conference about wage data. So we know that we don't get much in terms of labor cost data or wage data from the Eurozone or rather it's released with a lag. It's a quarterly series. It's released with a long lag. And it seems to be the case that the ECB is waiting for data from the first quarter of this year, which will come in May time before making a decision about whether or not it's the right time to be cutting interest rates. So they're data dependent, but it seems like they're waiting for a very specific piece of data, which is to say more information on what's happening in the labour market, particularly in the first quarter of this year. I think that the other key piece of data is that the inflation numbers are continuing to kind of point to underlying inflation slowing. So there's a tension there between the ECB wanting to see more in the way of disinflation from the labour market, but them having to wait for that data. And in the meantime, inflation pressures, consumer price inflation pressures seem to be abating. It's possible that I think that they could still cut in April, but it seems to be the message from the ECB seems to be that the summer's more likely. Now, strangely, the markets seem to take that as dovish rather than hawkish. If you look at the market moves over in the kind of 12 hours after the meeting, it seems to be interpreting the message as being dovish, despite the fact that they are quite clearly trying to push back on expectations of an April cut.

David Wilder

You mentioned the ECB's data dependency there. 'Data dependent' does seem to be a mantra for the meetings happening at the moment and in the coming weeks. When you say data dependent, what are the data points that we should be watching here? I know you mentioned wage growth, for example, but are we looking at any single releases or is it just the broad mass of numbers that come between now and what we think of those key meetings in the weeks, months ahead?

Neil Shearing

I think there are two things really. One is on the activity side, policymakers are going to have to continue to keep an eye out for any signs that economies are starting to crack. We talked about the US and how strongly resilient the US consumer in particular has been, but the Fed's going to be keeping a close eye on that for any early evidence that things there are starting to crack. And actually, if you look back all the way to 2001, for example, it didn't take much in the way of evidence or a signal that US consumption was starting to crack for the Fed to move in December of 2001. I think there was kind of one week car sales number and some size of the labor market and the jobless claims had gone up and the Fed moved. So any small evidence that activity's starting to crack could provoke a move from central banks. I the other key point, as you alluded to, is what's happening with wages and prices. Now on that front, I think two things are worth paying very close attention to. The first is whether this trend of falls in core inflation continue. And then the second is what's happening in the labor market with wage growth in particular. And that's the key thing, I think, for the ECB. That seems to be what they're putting more weight on. So as I say, that data is not really coming until May time for the first quarter of this year. In the meantime, they're going to be paying very close attention, I suspect, to things like prices paid, input -output prices in business surveys, some of the lower profile wage data that we get from some of the business surveys too.

David Wilder

One of our most read reports over the last few days has been this new analysis by Shilan Shah who heads our India coverage. It could be because it was highlighted in John Authur's Points of Return newsletter on Bloomberg. But the report that Shilan wrote makes this point that we've got this overall positive view on artificial intelligence, but maybe not so much for India in the near term at least, regardless of what we think about India's long -term economic outcome, which is pretty positive. What can you tell us about the idea that there are winners and losers from AI's emergence?

Neil Shearing

Yes, I think that's a really important point. The report on India itself found that in the next decade, the emergence of AI could knock about 0.3 percentage points off of annual productivity growth in India because it has a large business process outsourcing sector and it's precisely those types of jobs set in sectors that can come under threat from the emergence of Large Language Models. However, once this technology is rolled out and spreads across the globe, it will spread to emerging economies as well as developed economies. It will start in developed economies, but it will spread to emerging economies too. And so India gets the benefits of that later. Now, what does this mean? I think there are two big points I would make. The first is, this is a really good example of how the effects of AI will play out in different ways in different economies. I articulated that in my note last week about the broad economic impact of AI. We don't buy either that it's going to create large amounts of unemployment as some are concerned, but it's going to affect different economies in different ways. The US is going to remain at the vanguard of this AI revolution. Economies in Europe are going to be somewhere in the middle. And then economies in the emerging world will both lag behind in terms of the adoption, but also will feel some of the pressures in the very short term. So there'll be some losers. And I think India is a good example of this in the near term. The second point related to that is that time matters, the timeframes over which all of this play out will differ between economies. So in the US, we're already starting to see pretty rapid adoption. And I suspect we'll start to see that in the economic statistics over the second half of this decade. But it's going to take much longer for those benefits to play out for emerging economies because the adoption is going to take much longer. So different consequences in different economies and those consequences playing out across different timeframes in different economies.

David Wilder

Neil shearing there on data dependent central banks and on India's AI challenges. For more on monetary policy join our economist team after the Bank of England meeting on Thursday the 1st for a Drop-In - that's one of our short form online briefings. It's going to be all about the latest decisions from the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of England and what they mean for the policy outlook. We've also got a Drop-In this coming Wednesday, that's the 31st on Australian CPI and the case for an early rate cut from the RBA. Details of all of these on our events page, capitaleconomics.com/events. Our India analysis on AI, that's going to be on the podcast page and I'll also link to our broader work on the global impact of this technology. We'll be hearing in a bit about shipping disruptions and supply chains, but first to China, where the government's been belatedly scrambling to restore confidence in the economy and the stock market, including a reserve requirement cut that was unusually announced via press conference rather than the usual PBOC statement. Here's a clip from our Drop-in held shortly after that PBOC announcement, which discusses whether any of these measures will work. Chief Asia Economist Mark Williams led the session, talking with head of China Julian Evans-Pritchard and Senior Markets Economist Tom Matthews. And the clip begins with Julian talking about what's prompted this flurry of activity from the government.

Julian

Well, first off, I think if you had asked policymakers a few weeks ago whether they had been providing support to the economy, they would have argued that yes, that they had been providing fairly substantial support, particularly on the fiscal side. We had seen already a substantial ramp up in government borrowing. But obviously that hadn't been enough to kind of support confidence, particularly among foreign investors. And we continue to see markets perform poorly. And then when the PBOC didn't cut rates as everybody had expected earlier this month, that led to a further sell -off as a result of people thinking that they had lost the plot a bit and not really providing enough support and don't really realize how serious the economic situation is. So in response to some of the recent sell -off in markets, it seems like they've decided to take a more concerted approach, which is why we've had this flurry of announcements in recent days. And as you say, the way in which the triple R cut was announced was a bit unusual, suggests to me that perhaps it was a last minute decision in response to some of the sharp falls in Chinese markets that we saw at the start of the week.

Mark Williams

And so what sort of impact would we expect it to have? There's always a tendency, I think economists have, is to look at each individual thing that happens and say, well, that's not enough to make a big difference. But do you think that we're seeing enough different measures happening now to make, you know, an appreciable difference in the path of the economy over the next 6 to 12 months?

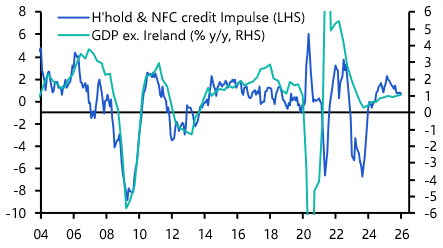

Julian Evans-Pritchard

Well, I don't think monetary easing is particularly effective at the moment. Things like the triple R cut, yes, it injects liquidity into the banking system. But the constraint on credit growth at the moment is not liquidity. It's not the sort of supply of loans. It's really on the demand side where the weakness is. So I suspect a lot of this additional liquidity is simply going to remain within the financial system probably a lot of it will just flow into government bonds, given the amount of risk aversion at the moment. So it helps to boost sentiment a little bit at the margins, but I can't see it really having a significant positive impact on the economy. Where we do think there might be a real impact is on the fiscal side. And in fact, we were already starting to see some of that feed through towards the back end of last year, which is why some of the data, the monthly data at least were showing signs of a slight improvement. There was pick up in infrastructure investment, industrial production doing pretty well at the end of last year, and even some signs of some improvement in consumer sentiment as well. So I do think policy support is having some impact, but the problem is that all of the heavy lifting is being done by fiscal policy. And even though they're pushing quite hard on that lever with appetite for borrowing and for spending so weak in other parts of the economy, you're just not going to see the same cyclical pick up to, or at least not to the same extent as what we've seen during previous rounds of stimulus. So although we do expect some modest improvement over the next few months, it's going to be a fairly weak recovery by par standards. So on the macro side, near term, moderately positive, but we don't think it's going to be.

Mark Williams

Fantastic. And Tom, can I bring you in on the market side? I guess, particularly equity markets recently has been the focus. There were some pretty big jumps earlier in the week to the back of some of these announcements. What's your thinking on how sustainable that is? Are these just short -term things that will unwind, which has been the case, I think, with previous announcements like these? Or is there a case to be a bit more upbeat about Chinese equities?

Tom Mathews

Yeah, look, as you say, I think you look at each of these individual things that seem to have boosted the stock market, whether that's announcements about stabilization funds or these, perhaps, these RRR cuts and so on. And I think you look at those individually and you think, well, none of these should really be long -terms, a staying boost for equity markets. I think the point that we've been making for quite a while, and I still think is true, is that a lot of the weakness of charter stock market hasn't really been about the fundamentals of the economy, per se, at least not directly. A lot of it's really just been about investor sentiment. There's huge fall in valuations rather than necessarily expectations. And sure, some of that is probably worries about the economy. But some of it, I think, is also worries about authorities' attitude towards the stock market, or at least towards the private sector more broadly. We have seen over the past few years these various sort of crackdowns, these things that they've done that have limited the potential for profits. And they've really tried to sort of constrain the private sector. And investors are naturally worried about that. The flip side of that is that when you do get announcements like this, it's not just about the announcement per se. It's about what policymakers are signaling to investors. They're signaling a sort of a more pro -investor stance than they might have been in the past. They're signaling a more sort of pro -growth stance than they might have been in the past. I think that's why investors reacted so positively to this above and beyond what might sort of direct the shift. Now, could that continue to boost the stock market? I think quite possibly it could. I mean, yeah, there've been some big gains over the past few days, but really all that does is erase like a week or two of losses. We're still at a point where investor mood, if you like, towards Chinese equities is really, really bad. It's quite downbeat. Valuations, you know, even after these gains, are still going to be basically at the widest discount to global equities that they've been in about 20 years. You know, earnings expectations, although they've grown, some sectors are still not particularly optimistic. So I don't think you necessarily need a whole huge amount of good news to keep boosting China's stock market. As you say, it could be something as simple as moderately positive growth over the next few months. Yeah, it really sort of beats, well, still seem to be pretty depressed expectations for investors, and that could boost the equity market a bit more.

David Wilder

Tom Matthews there and you also heard Julian Evans-Pritchard and Mark Williams discussing China's beleaguered economy and markets. The clip was taken from our latest monthly Asia Drop-in and I'll post a whole recording of the session on the podcast page. It also includes discussion about the latest from the Bank of Japan and India too. Finally this week, we've been tracking disruptions to shipping in the Red Sea for weeks to gauge where the rising geopolitical tensions could lead to resurgent inflation. Our Global Economics team has now enhanced that analysis with a new dashboard which presents the most comprehensive and timely view in the market of risks to the global economy and asset prices. I spoke to Simon MacAdam, our Deputy Chief Global Economist, about these risks and what the dashboard says about them. And I started by asking him to compare the current situation with the supply disruptions that we saw during the pandemic.

Simon MacAdam

I think the disruptions we're seeing today differ from the pandemic in two key respects. The first is simply the geography is different. So today, given the nature of the attacks are taking place in the Red Sea, that means that it's the Suez Canal that's being particularly affected, which means that means Asian European shipping routes where most of the disruption is occurring. Compare that to the pandemic when it was mainly the trade between Asia and North America. That was the epicenter of the shipping problems back then. Suffer first in the first respect. But more fundamentally, I think what we're seeing now differs from the pandemic in terms of global supply chains and the global shipping industry and the global logistical network more broadly is in a better place to cope with this disruption than it was back in 2021 and 2022. You see, back then you had a huge surge in demand for goods and the shipping industry was struggling to keep up with that. Today, we've got a disruption to the shipping supply, but the demand environment is much more subdued and we've got excess capacity operating at the warehouses, in the trucking industry, at all these different points along the logistical network. There is ample capacity to deal with disruptions.

David Wilder

We've got that pandemic era, the supply demand shocks, seared in our memories. We just touched a bit on what we're seeing along supply chains. But talk a bit about whether we're seeing any disruption at this point.

Simon MacAdam

So far, we are getting quite expectedly really anecdotes popping out to some wholesale name companies, some auto manufacturers, some retailers complaining about shipping delays and what that might do for their cost base. So we're going to some anecdotes from individual companies. But even in the case of the auto sector, they are only experiencing temporary shutdowns to production. So they're talking about sort of closing factories for two weeks while the parts take longer to arrive. Beyond those anecdotes, thinking in terms of the macro data, I mean, this is what we've done in terms of creating this new shipping disruption dashboard on our website, is to try and bring together all the evidence in terms of the macro picture on what's happening to supply chains. And so far, it's a bit too early to tell. I mean, we can see from using satellite data, we can see what's happening in terms of cargo volumes being imported into ports around the world. And we can see that they have dropped off in recent weeks. But given the volatility of the data, it really is too early to tell whether that's a really meaningful hit to global supply chains. And secondly, we've just had just this week, the flash PMI surveys were released for advanced economies in which firms are asked about whether their delivery times are lengthening or shortening. And we did see in a few of those surveys a pickup in delivery time. So we're starting to see the very early impact on global supply chains, but at this stage it hasn't been particularly large.

David Wilder

A lot of the commentary about the inflation threat that this situation presents focuses on that spike in freight rates, which are being treated as some kind of leading inflation indicator. Is that how we see price levels ultimately being affected here? Talk about what we're seeing on these freight rates indicators.

Simon MacAdam

I mean, we are seeing very, very big increases in spot freight rates for container shipping, particularly on those most affected routes. So between Asia and Europe, they've really jumped several hundred percent. Other routes have been much less affected, but that particularly has jumped by a very large extent. And so consequently, that leads people to say, well, if shipping costs are rising, to such an extent that surely this is going to stoke inflation and is this just happening at just the wrong time? Just as we thought that central banks had defeated inflation and got inflation close to targets and it's coming drifting back down to target and they're getting ready to cut interest rates, could this be happening just at that time and actually spoil the party and stoke a resurgence in inflation? I think that's the wrong way to think about it. I mean, firstly, there is a difference between the spot freight rates that everybody talks about and gets all the headlines in the media and actual total shipping costs. The majority of global shipping is still done on a contractual basis, securing shipping deals and slots and containers for a year or more. Those rates are rising too. We're already starting to see that in the data, but to a far smaller extent than the spot freight rates are rising. That's the first thing I want to say. And the second thing on that is that if we just think through what the potential impact of higher shipping costs would mean for overall inflation. And the point here is that shipping costs, to make up such a small fraction of the value of goods and services that are consumed in an economy, that you'd have to see meteoric rises for that to really move the needle at the macroeconomic level. And this is what we saw in 2021 and 2022. So during the pandemic, we saw far larger increases in global spot rates. When we saw 900 % increases in shipping, we're sort of more of the sort of 200 to 300 % at the moment on key routes. And even when we saw those 900 % increases in shipping costs,

we estimate this that possibly added about 0 .3 percentage points to global inflation. The context was that global inflation rose from 3 % to 8%. So you had a 5 percentage point increase, about 0 .3 percentage points of which we think could be attributed to shipping. And that was despite a far bigger increase in shipping costs.

David Wilder

Not much evidence so far of supply disruption. The spot freight rates, not a particularly good indicator of inflation risk here. But where are the risks in this situation? Looking at the conflict, looking at the region, how do we frame the inflation risks associated?

Simon MacAdam

Yeah, I mean, when you get past that direct pass -through of higher shipping costs to consumer prices, I think more broadly, if you think about this, is just a general supply issue. So if you have shipping disruptions that are widespread enough, that are prolonged enough to cause problems across global supply chains, then that itself could induce and bring about shortages of goods, which then stokes inflation. So it's rather than it being a direct pass through of shipping costs themselves boosting inflation, arguably shipping could contribute to a supply chain problem that ultimately ends up with higher, you end up with higher inflation at the end of that process. That's why it's so important for us to monitor the knock on effects of the disruption from the Red Sea on global supply chains. And that's why we'll be watching our own dashboard very closely for evidence of widespread disruption. The thing I would say about this, the thing that gives me some comfort is that we are in a far better place than we were back in the pandemic. Inventories of manufactured and retail goods are relatively at healthy levels relative to the state of demand. Various indicators and surveys suggest that firms are not reporting prevalent shortages to begin with and there's excess capacity along the logistical network. So all in all, I think at the moment the risks are relatively contained that we're going to get the sort of shortages that could stoke inflation. So in that case, the question could be, well, the shipping costs themselves are unlikely to boost inflation materially. And we're relatively reassured by the latest data on the state of global supply change. What is the real inflation risk of all of this? And I think rather than the shipping issues themselves, I think it's the wider geopolitical situation. It's the wider military conflict. Now, at the moment, that is not significantly endangering energy supplies and so energy prices have not been surging. But if, let's say, that military conflict did escalate in a way that did seem to endanger energy supplies, then that's a different ballgame. But going by the stability of energy prices in recent weeks, I think it's fair to say that oil traders and gas traders themselves consider this quite a tail risk.

David Wilder

Simon McAdam there on supply chains and our shipping disruption dashboard. I'll link to a special chart pack that he's put together of some of the key indicators from the dashboard for complete access, including to the underlying data. You'll want CE advanced. That's our premium platform, but that's it for this week. Neil will be back next week to unpack those Fed and Bank of England decisions. I'll also be talking to the team about distress in commercial real estate and much more beside.

Until then, goodbye.