A persistent feature of the post-pandemic age has been the relative strength of the US economy and equities market. But past performance is no guarantee of future results. Will the US continue to dominate the world economy, and its markets to outperform global benchmarks? Yes and no.

No recent phenomenon

Our annual Spotlight project launched last week explores whether the US will continue to dominate the global economic system. It highlights the extent to which the American economy and its equities markets have moved ahead of their peers since the pandemic. Over the past two years, US GDP has grown by 4.3%, compared to just 1.3% in the euro-zone and zero growth in the UK. The return on US equities in that time has been 1.6 times larger than the return on the MSCI ex-US World Equity Index.

But this is about more than just a temporary period of economic outperformance. The American economy, which has been the world’s largest since the 1870s, and has been doing better than its developed market peers for decades, with real GDP growth averaging 2.25% a year since 1990 compared with 1.7% in the UK, 1.4% in France and 0.7% in Japan. In that time, major emerging markets such as China and India have grown faster, but this has been so-called “catch-up” growth from what are still relatively low levels of income. Measured at market exchange rates, China’s GDP per capita is still only 30% that of the US, while India’s is just 10%.

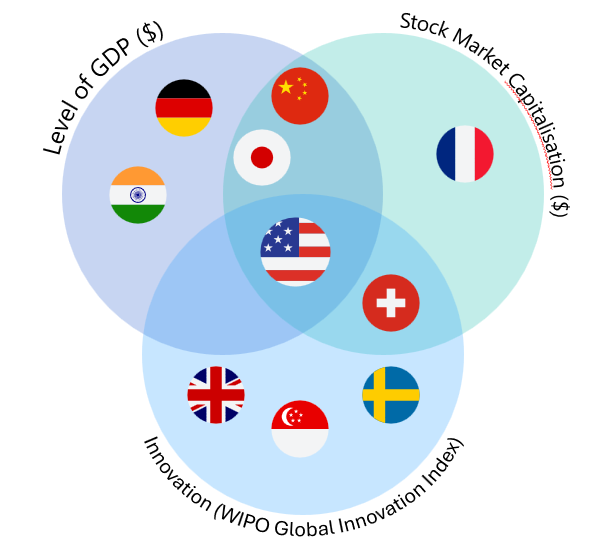

Our Spotlight report and accompanying data make clear that American economic dominance has been about far more than the pace at which its GDP has been increasing. The US dominates the rest of the world in economic, financial and technological terms. Yes, it faces challengers in some areas. China’s economy is now close in size to that of the US, while Singapore and Switzerland rival the US on measures of innovation and technological leadership. But the US is the only economy that ranks in the world’s top five on measures of GDP, financial market depth, and technological innovation. (See Chart 1.) It is from this that America derives its global economic and market heft.

|

Chart 1: The World’s Top 5 |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, WIPO, Capital Economics |

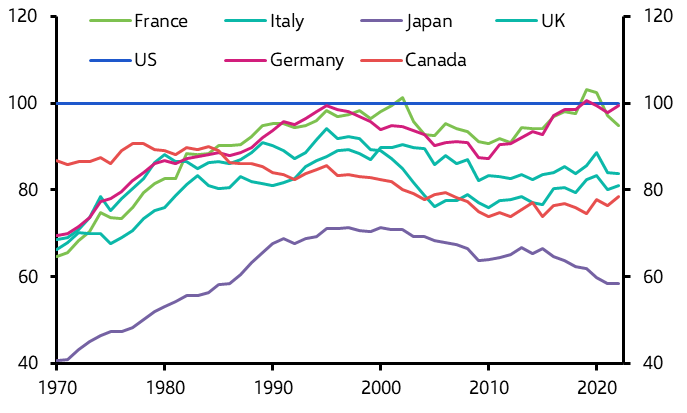

America’s strength is partly a function of its relatively large population, the world’s third largest. But real global dominance requires high levels of productivity alongside a sizeable population. As Paul Krugman famously said, “productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it's almost everything”. And America has been consistently more productive than its economic rivals for a long time (See Chart 2). A variety of factors work in the US’s favour on this front, including deep capital markets, an ability to attract skilled migrants, high R&D spend and an entrepreneurial culture.

|

Chart 2: Output Per Hour Worked (As of a % of US, $, constant PPP prices) |

|

|

|

Sources: Eurostat, US Census Bureau, ITC Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Could America cede its advantage?

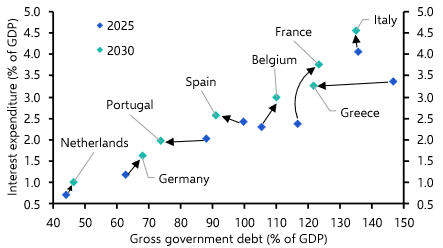

We’re frequently asked whether the dire state of America’s public finances could result in a fiscal crisis. The trajectory of the US’s public finance is unsustainable and a significant fiscal consolidation of about 2-3% of GDP is required to put them on a more sustainable footing. There is clearly a risk that the markets could force the government’s hand on this front. However, this is not yet our central scenario. And while a fiscal crisis would cause a significant hit to GDP over a two-to-three year period, it would be unlikely to permanently lower productivity growth, which is key over the longer run.

A more immediate threat is an embrace of economic isolationism under a second Donald Trump administration. This will come into greater focus as we approach November’s election. However, it would require a sustained assault on the attitudes and structures that underpin America’s success in order to shift the economy to a permanently lower growth path. Once again, this is not our central scenario.

If Trump were re-elected and set in train a radical agenda that undermined the US institutional set-up, the immediate effects would undoubtedly be wrenching. But this is far from guaranteed and, even if it were to happen, we suspect that the dynamism of the economy would be likely to withstand the erosion of institutions, provided that the norms, values and culture that have underpinned US success endure. It's worth noting that a shift towards isolationism in the 1930s did not dislodge America’s position as the world’s dominant economy.

Challengers likely to fall short

At the same time, it is hard to imagine any other country or region mounting a serious challenge. Countries like Korea, Japan and Singapore will remain technological leaders, with some countries leading in areas like green technology. But a serious contender for global economic dominance needs sufficient scale and technological expertise, criteria which quickly narrow the field to just Europe and China.

China will be hindered by a state-led model pursuing priorities other than economic performance. The fracturing of the global economy will also restrict China’s access to western technology and markets. And, as we have explained, it is difficult to see how the renminbi could seriously challenge dollar dominance. Network effects mean global trade will continue to be mostly dollar-denominated, while its export-led model and associated current account surplus mean that China is unable to provide the rest of the world with enough safe, liquid and convertible renminbi-denominated assets to compete convincingly with the greenback.

Europe is disadvantaged by its demographics, while the likelihood of structural reform capable of significantly improving its inflexible labour markets and regulatory environment seems low. Europe’s slow adoption of previous advances in computer technology means it will also struggle to gain the advantage in this next wave of innovation. And the euro-zone will remain constrained by its lack of a federal structure and absence of unified fiscal arrangements, capital markets, or banking system.

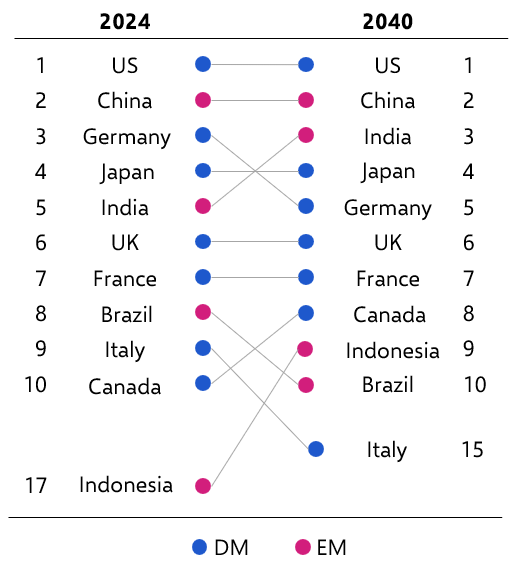

Accordingly, despite its evident flaws, that leaves the US as the biggest, richest and most dominant economy for the foreseeable future. (See Chart 3.) If anything, the US is likely to widen its performance gap with other developed economies in per capita GDP terms (measured at market exchange rates) over the coming years. And while China will narrow the gap with the US in terms of GDP per capita, demographic headwinds mean we doubt it will ever overtake America in terms of overall GDP.

|

Chart 3: World Rankings by Nominal GDP at $ Market Exchange Rates |

|

|

|

Source: Capital Economics |

Economic outperformance ≠ market outperformance

But stock market buoyancy, the other feature of American outperformance since the pandemic, may prove less resilient. Earnings per share and valuations have risen sharply on the back of a strong economy, while equities have also been helped by optimism around artificial intelligence – particularly large tech firms.

We suspect that this optimism will continue to propel the US market over the next 18 months. But enthusiasm around AI has all the hallmarks of an inflating bubble. Once it bursts – as it inevitably will – the US stock market will be destined for a period of significant underperformance relative to its peers.

This raises the question of whether a bursting equities bubble in itself threatens the US’ global economic position. It didn’t in 1929, nor in 2001. The drivers of US dominance are too fundamental to be challenged by the occasional bout of irrational exuberance.

Data and charting: Alongside our Spotlight report we published an interactive dashboard that allows clients to access the underlying data and charts and use them in their own work. This includes using data in internal models, and charts in investor committee packs and client newsletters. Get in touch if you would like to know more about how clients in your area are putting our data to work.

In case you missed it:

Following on from Spotlight’s launch, Bill Weatherburn showed why US energy supplies will impede its transition to renewables, in contrast to what’s happening in Europe and China.

Hubert de Barochez reviewed a tough week for French markets as political turmoil spilled over, and explained what’s to come.

Our analysis of announced EU tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles highlighted key differences with the US approach.