Nobody knows where US tariff policy will ultimately land but one thing is starting to become clear: the Trump administration has China in its sights. The exemptions for various electronic goods, including smartphones and laptops, announced over the weekend has reduced the effective tariff rate on imports to the US from China a little, but it still stands at just over 100% – up from about 12.5% at the start of this year. The short term consequences will be higher prices for US consumers. But if tariffs are maintained at these levels over the long term they will have the effect of dramatically cutting trade between the world’s two largest economies.

Why has China been singled out by the Trump administration? The size of China’s bilateral trade surplus with the US has clearly played a role, as has its aggressive retaliation to each round of US tariffs. But this tit-for-tat escalation is being driven by something more fundamental: a deepening superpower rivalry between Washington and Beijing that has set both countries on a collision course. This is something we’ve analysed extensively and is the subject of a book I have written that will be published this August called “The Fractured Age”.

|

Image 1: ‘The Fractured Age’ by Neil Shearing

|

The title says it all: we’ve entered a period in which the global economy is fracturing into blocs. While this fracturing could take several forms, the most likely outcome remains that the world coalesces into blocs centred on the US and China. And while the current focus is on trade and supply chains, fracturing will also affect everything from cross-border flows of capital and technology, to efforts to secure critical minerals.

Fracturing in practice

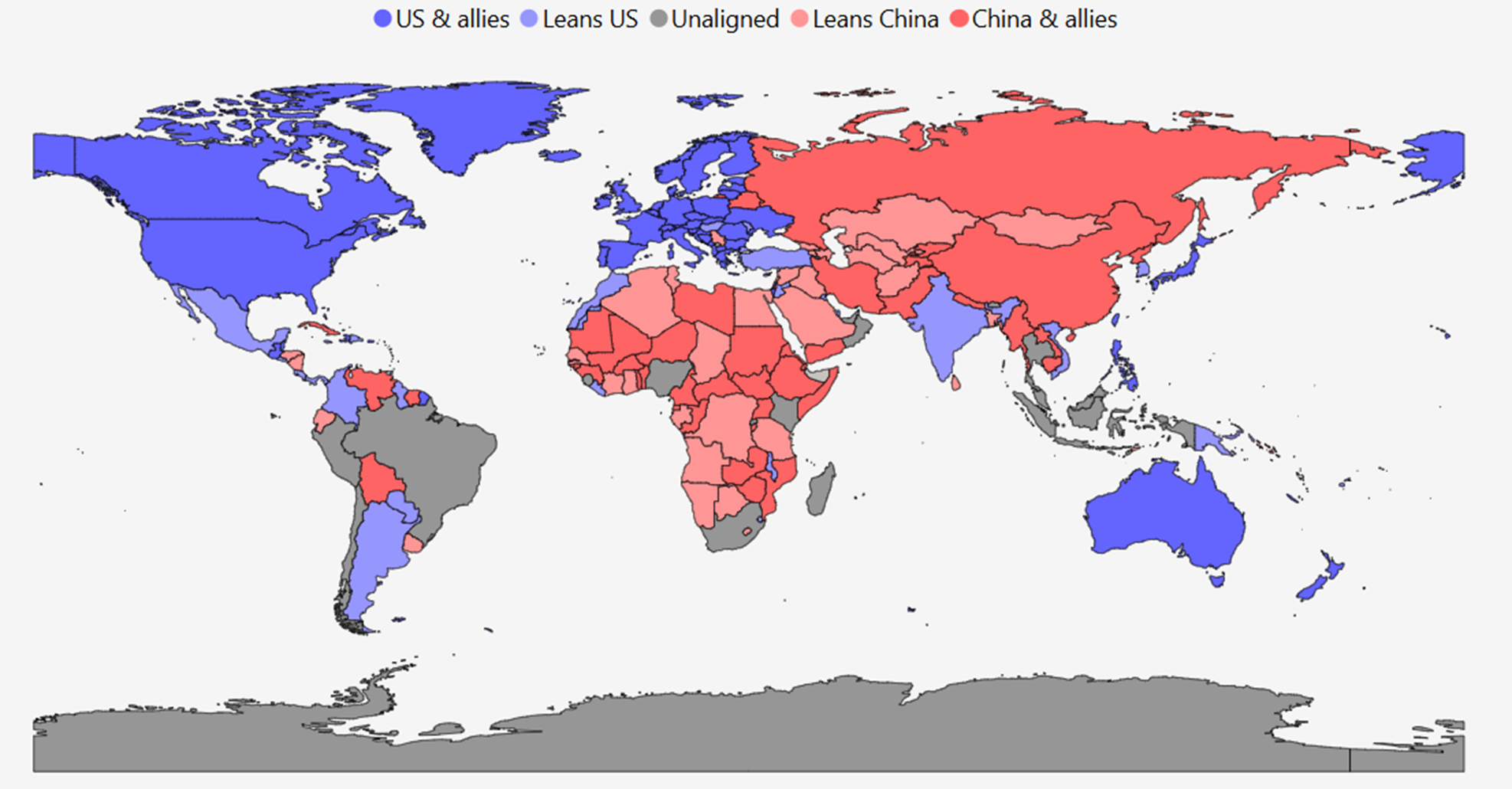

Developments over the past month or so illustrate how this fracturing is likely to play out. First, in response to the imposition of tariffs on China, Apple announced that it would source more iPhones for the US market from its facilities in India – a country that falls into the US bloc on our fracturing map, and which has been hit by lower tariffs than China. (See Chart 1.) This is a good example of how fracturing will affect global trade and supply chains. It will not necessarily result in less cross-border trade – rather, it will affect the direction of trade flows. The result is likely to be greater fragmentation of global supply chains, with some elements configured to serve the US market and others configured to serve China.

|

Chart 1: Capital Economics’ Classification of Geopolitical Alignment

Sources: Capital Economics |

Second, a key element of China’s response to the initial round of US tariffs was to restrict export of various types of rare earth minerals to America. This has become part of Beijing’s playbook when pushing back against Washington. China has a virtual monopoly on global supply of some rare earths, and the supply of many other critical minerals – from cobalt to palladium – is concentrated in countries that align with Beijing. (These are primarily in Africa and Latin America - again, see Chart 1.) The weaponising of this control over critical minerals – and the race by other countries to secure alternative supplies – will be a central feature of a fractured global economy. This will result in large fluctuations in commodity prices, as their supply is restricted (pushing up prices) and then new sources are developed in response (pushing them back down). A fractured world is therefore likely to be one in which inflation is more volatile, rather than necessarily higher.

Finally, fracturing will have a significant bearing on global capital flows. Chinese selling may have played a role in driving up yields at the long end of the US Treasury curve over the past week, although as we’ve noted before large divestment by China would be self-defeating since it would reduce the value of its external assets and there are few alternatives to dollar-denominated securities. But it is likely that cross-border investment flows will become more politicised in a fractured world. The so-called “America First Investment Memorandum”, issued by the White House in mid-February, provides a blueprint for how this might happen in practice. It explicitly called for greater investment from US allies alongside restrictions on investment from China. The $100bn investment in the US announced last month by Taiwanese chip-maker TSMC is consistent with the idea of Washington strengthening relations with traditional allies in strategically important areas.

Playing the long game

Where do we go from here? Crucially, while US politics is divided on most issues - including the wisdom of imposing large tariffs on America’s allies – lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are united on the need to push back against China. Similarly, China believes that it is the economic ascendancy and views itself as a necessary bulwark to US hegemony. This is important because the forces shaping fracturing are bigger than one man, important though he is. The process will therefore continue long after the 47th President departs the White House.

Where this ends up is still uncertain. One of the biggest risks for the US is that it alienates its allies – the size and economic diversity of which are one of its major strengths in a fractured world. Another, altogether more serious, threat is that an ever-deepening rivalry brings the US and China into conflict. By the same token, however, Apple’s India announcement shows that while the world as a whole will be worse off as a result of a more fractured system, there will be benefits for some. Identifying the potential fault lines of a fractured world will be crucial to understanding where the challenges and opportunities lie – and to successfully navigating the path ahead.