So much for the summer lull. Stock markets are in turmoil and bond yields have plunged as fears about a US recession have taken hold. For all the challenges in gauging where economies and markets are heading amidst massive spikes in volatility such as we are seeing, it’s clear that there are three pressing questions for investors:

1. Is the US heading for recession?

While economists use two successive quarters of falling GDP as short-hand for recession, true recessions start when “reflexivity” in the jobs market kicks in: weaker demand leads to less hiring and more firing, which feeds back into weaker demand, creating a vicious cycle that is only broken with policy support. This is why the labour market data are critical to assessing recession risks, and why there has been such an extreme reaction to July’s Employment Report released on Friday. It wasn’t just that payrolls missed consensus expectations – rising by 114,000 vs 175,000 expected – it was that the unemployment rate rose to a three-year high of 4.3%, thus triggering the Sahm Rule, an indicator of recession.

But some perspective is needed. The rise in the unemployment rate has so far been driven by an expansion in the labour force rather than a fall in employment. This marks a difference from previous cycles. What’s more, it is likely that that Hurricane Beryl contributed to weakness in July’s payrolls figure. Other data paint a picture of a labour market that is cooling, but not collapsing. Data also released last week showed that, while job openings in the US held steady at close to a three-year low in June, there has been no increase in firings. Furthermore, the modest decline in average weekly hours worked seen in July’s Employment Report does not scream “recession”.

Piecing all of this together, our US Macro Scenarios Dashboard shows that the probability of a ‘Goldilocks’ outcome – in which GDP growth remains above 1.5% q/q annualised and core PCE inflation drops to 2.5% or below – has edged down to 38% from 39% last week, while the probability of a hard landing has risen to 27% from 20%. In other words, the risk of a recession/hard landing has increased, but there is probably something like a one-in-four chance of this happening. Big questions that flow from here are whether the dislocation in financial markets seen over the past week feeds off itself and creates a vicious cycle that feeds back into the real economy and how the Federal Reserve responds. On which note…

2. How will the Fed respond?

The Fed’s response will be determined by two factors: the extent to which downside risks to the real economy materialise, and whether the sharp sell-off in financial markets causes something to break. This would then create a feedback loop into the real economy through tighter credit conditions.

We argued for most of the first half of the year that the Fed should begin cutting rates in May, and I’ve noted before that, by waiting for core inflation to return to target, central banks more generally risk keeping policy too tight for too long (since inflation is a lagging indicator). July’s Employment Report suggests that these risks may be starting to crystallise. With that said, while the report was bad it wasn’t that bad. As I noted earlier, while the respective probabilities of a hard and soft landing in the US are converging, our scenarios dashboard still suggests that the latter is the most likely outcome.

Given all this, our sense is that the Fed will now cut by 25bps at each of its three remaining meetings this year. It would take one of two developments to trigger a larger 50bps cut (or intra-meeting move). The first is a market dislocation that deepens and starts to threaten systemically important institutions and/or broader financial stability. The extent to which this will happen is inherently unknowable. But it’s worth keeping in mind that a rapid appreciation of the yen, and the subsequent unwinding of carry trades, have played a role in previous periods of acute market stress, including the collapse of the hedge fund LTCM in 1998.

The second is if markets continue to price in a 50bps cut in September (and beyond) and policymakers judge that not delivering it would do more harm than good for financial markets. The fact that the inflation genie appears to now be back in the bottle means the Fed has more leeway in this regard. This is not true of all central banks – which brings us to…

3. How will other central banks respond?

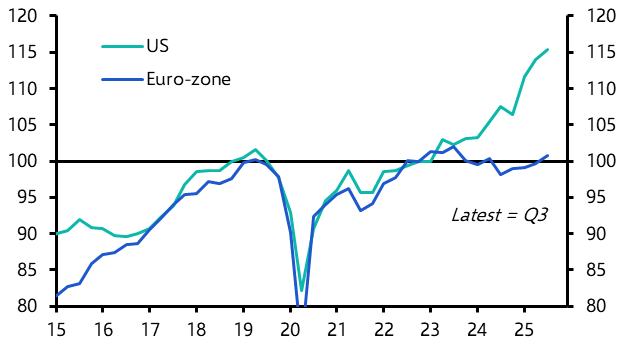

Many central banks are still trying to calibrate policy in an uncomfortable environment of weak growth and stubbornly high inflation. This is particularly true of the ECB. While euro-zone GDP increased by a solid if unspectacular 0.3% q/q in Q2, Germany – which is the region’s largest economy and its industrial powerhouse – contracted by 0.1% q/q. Set against this however, inflation data released over the past week showed that HICP inflation edged up from 2.5% y/y in June to 2.6% in July, and services inflation continued to hover around 4%. The latter is of particular concern since it more closely reflects domestically driven price pressures. This has given ammunition to a vocal set of hawks on the ECB’s Governing Council.

As things stand, our sense is that doubts over the outlook for the US economy – combined with a softening in euro-zone business surveys in recent months – will mean that policymakers opt to lower interest rates by another 25bps to 3.5% at its September meeting. The same is likely to be true for other countries; where previously a decision may have been finely balanced, now central banks will err on the side of looser policy. Next up is the RBA, which meets tomorrow. A final hike looked possible only a few weeks ago. It is now likely that rates are left unchanged.

Finally, recent market movements raise questions about the Bank of Japan policy outlook. We were in a minority of analysts who correctly forecast last week’s rate hike, and had pencilled in a final 20bps increase at its next policy meeting in October – a lifetime away in the context of recent market developments. Underlying inflation and the looseness of Japan’s real monetary policy stance argue for another move in October, but the yen’s stunning rebound is a reason for policymakers to stand pat.

Note: Our US and Markets teams will be holding a Drop-In today at 0830 ET/1330 BST to address recession fears and the outlook for stocks and bonds. Register here for the 20-minute online briefing.