- China has had a stellar run during the past few decades, achieving sustained rates of growth only ever previously seen in a handful of emerging economies. Most major forecasters expect this outperformance to continue for the foreseeable future. By contrast, we think that China’s growth rate will decline to as low as 2% by the end of the next decade.

- Bearish views about China have become more common in recent years but the mainstream consensus view now seems to be that the bulk of China’s slowdown since the global financial crisis is over. On this assessment, China will have its ups and downs. But it will continue to gain ground rapidly on developed economies, achieving high income status and surpassing the US as the world’s largest economy at market exchange rates within the coming decade or shortly after.

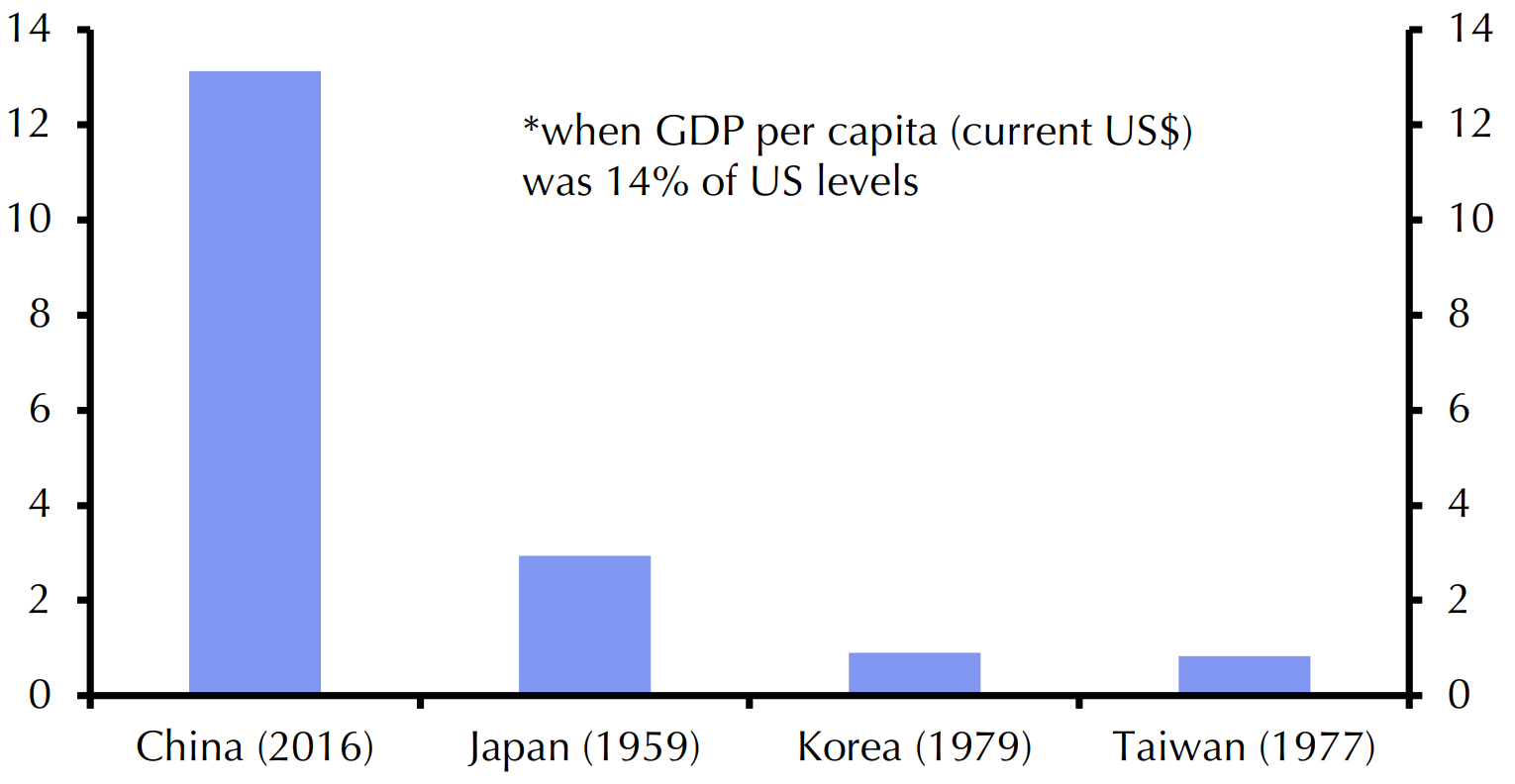

- We are sceptical. Over recent decades China has followed a similar growth trajectory to Japan, Korea and Taiwan, which are among the few EMs that have successfully made the transition to high-income status. But China is reaching the limits of investment-led growth at a much lower level of income than its northeast Asian neighbours did.

- China’s unprecedented reliance on investment to shore up growth during the past decade means that it already has a large capital stock relative to the size of its economy. With remarkably good infrastructure for its income level and an ample supply of modern housing, the need for further rapid growth in construction has diminished.

- And while Japan, Korea and Taiwan were still rapidly expanding their manufacturing sectors (and exports) at this stage in their development, there isn’t enough global demand to sustain such growth in China. China’s share of world exports is already higher than its neighbours’ ever were and it is already running into a protectionist response.

- China is also growing older much sooner than its Asian peers. A declining working age population means that employment will start contracting this year, something that only happened in China’s neighbours once they had already reached high income levels.

- China’s only hope of sustaining its current rate of economic expansion is therefore to find more effective ways of raising the productivity with which its workers and capital are deployed. Unfortunately, the current trajectory of policymaking seems more likely to hinder rather than help.

- Instead of liberalising to sustain growth as the country gets richer, as nearly all countries that made the transition to high income levels did, the Communist Party appears intent on retaining control over large swathes of the economy. State intervention is already harming productivity and is likely to be a growing constraint: it becomes harder for state planners to allocate resources effectively as a country gets richer.

- The upshot is that, barring a major shift in the reform agenda, a combination of weaker investment, population aging and continued state intervention are likely to push China off the track of Asian outperformers towards a path much closer to that of a typical emerging economy. On this basis, we expect China’s trend rate of economic growth to fall to around 2% by 2030.

The coming slowdown in China

Consensus expectations for China’s economy since the global financial crisis have generally been too bullish. In its October 2011 World Economic Outlook, the IMF predicted that Chinese GDP would still be growing at 9.5% in 2016. The IMF was far from alone in its optimism at the time.

We’ve tended to be more cautious – a few months before the IMF published this projection, we predicted that growth would drop to 7.5% by 2013. (See our Focus, “Is investment-driven growth running out of steam?”, 2nd August 2011)

More recently, we argued in late 2015 that most had become too bearish on China in the wake of the stock market collapse and renminbi depreciation, and that growth was likely to recover during the following year. (See our Update, “What to expect in 2016”, 10th December 2015). There has been a marked turnaround in sentiment since then, with concerns about the health of the economy shelved in the face of evidence showing that the economy has been growing once again at a rapid rate.

This Focus argues that consensus expectations for China’s long-run outlook are now again too optimistic and that, despite the cyclical strength of the past couple of years, the structural factors that have dragged down growth since 2011 haven’t gone away. Indeed, in some cases, these drags on growth will intensify during the coming decade.

Xi is aiming high…

Although there has been some effort to move away from an emphasis on growth at all costs, China’s leaders clearly still have high ambitions for future economic performance. They have set a GDP growth target of “about 6.5%” for this year. And a commitment to double GDP by 2020 relative to 2010 levels in order to create a “moderately prosperous society” implies that they will target similarly rapid growth to the start of the next decade.

No hard targets have been set for growth beyond 2020. But Xi has set goals of China being a “modern socialist country” by 2035 and a “rich and powerful socialist country” by 2050. Implicit in this bold vision is that China continues its rapid climb up the development ladder, reaching high income status in the coming decades.

…but the odds aren’t in his favour

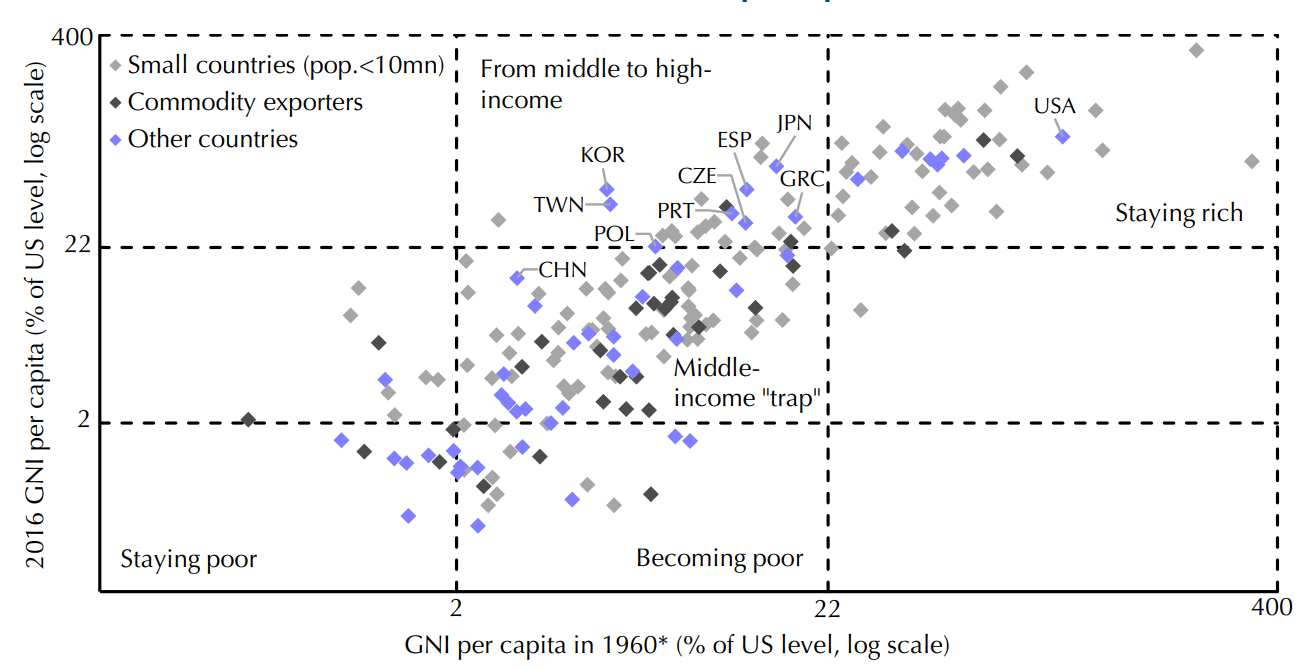

Chart 1 on the following page highlights how difficult it is for countries to enter the club of high income economies. It compares per capita income levels in 1960 with their levels in 2016 for nearly all economies in the world today (204 in total).

The most widely used definition of “high income” comes from the World Bank which, since 1988, has set annual GNI per capita thresholds for different income classifications. (GNI is used instead of GDP since it includes net income from abroad. In most cases, however, the difference between the two measures is small.) The latest thresholds, based on income in 2016, are listed in Table 1. We have benchmarked these against US levels and use the ratios to set comparable income thresholds for 1960.

Table 1: World Bank Income Thresholds (2016) |

||

|

GNI per capita ($) |

% of US level |

|

|

Lower-middle income |

1,005 |

2 |

|

Upper-middle income |

3,956 |

9 |

|

High income |

12,236 |

22 |

|

Sources: World Bank, Capital Economics |

||

As Chart 1 shows, most countries which failed to meet the cut-off for high income status in 1960 still failed to meet it in 2016. (In other words, nearly all of those to the left of the vertical 22% line for 1960 also lie below the horizontal 22% line for 2016.) Indeed, among the 156 low and middle income countries in 1960, a mere 25 had achieved high income status by 2016 – a success rate of only 16%.

This is often blamed on what’s known as the “middle income trap” – based on the observation that, by failing to move up the value chain, countries often get stuck at middle income levels.

In practice though, there doesn’t seem to be any specific income level at which countries get stuck. Instead, sustained rapid growth is unusual at any income level. Countries appear equally likely to remain low-income as they are to remain middle-income: the “middle income trap” doesn’t exist.

Indeed, income levels in emerging economies don’t typically grow much faster than those in developed economies. Among the 156 low and middle income countries in 1960, the median increase in GNI per capita relative to US levels by 2016 was a mere 1.3 percentage points.

|

Chart 1: Gross National Income (GNI) per Capita – Now vs 1960 |

|

|

*In cases where there is no data for 1960 earliest year available is used. Sources: World Bank, Taiwan DGBAS, Capital Economics |

China’s goal of achieving high income status appears even more ambitious once we take a closer look at the countries that have “made it” since 1960.

Of the 25 countries that have become high income, more than half (15) have a population of less than 10 million. Being small is no guarantee of wealth, but it does make it easier to climb to the top of the income ladder off the back of success in just a handful of sectors, often with a heavy reliance on foreign labour. This is not a model that China, with its population of 1.4 billion, can replicate.

Then there is Saudi Arabia and Chile, which achieved their rise to riches off the back of enormous oil and copper reserves. As a net commodity importer, China is in a very different boat.

This leaves eight remaining success stories which we have labelled in Chart 1. They can be split into two groups.

The first are European countries – Spain, Portugal, Greece, Poland and the Czech Republic. While they offer some lessons for China, they have also benefited from some unique factors, the most important being their integration with larger and richer neighbours as part of the European project.

Admittedly, China is pursuing regional integration via the RCEP trade deal and its Belt and Road Initiative. But the integration being pursued is less ambitious than what has been achieved in Europe. And in any case, China cannot ride the coattails of a larger neighbour since it is already the largest economy in Asia.

It is the second group – made up of Japan, Korea and Taiwan – that offers a relevant comparator for China. Indeed, in recent decades China has followed a very similar development path to its northeast Asian neighbours.

There is a widespread perception that China’s growth story is unique. In some respects it is. The country’s period of rapid expansion began when China was very poor: its per capita GDP was a mere 1.5% of US levels in 1978, when Deng Xiaoping launched the reforms that helped jumpstart growth. It took two decades of growth for incomes to reach Korea’s post-war low of 3% of US levels, and even longer to reach the post-war lows in Taiwan and Japan. This low starting point and China’s huge population help explain why China’s growth spurt has been unprecedented in its length and has lifted a record number of people out of poverty.

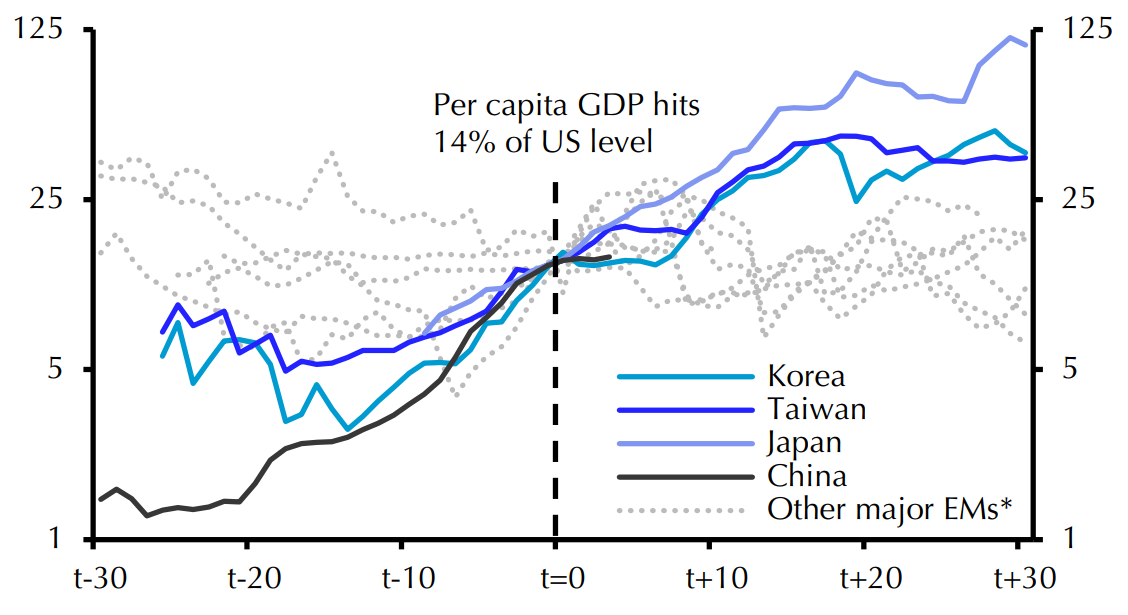

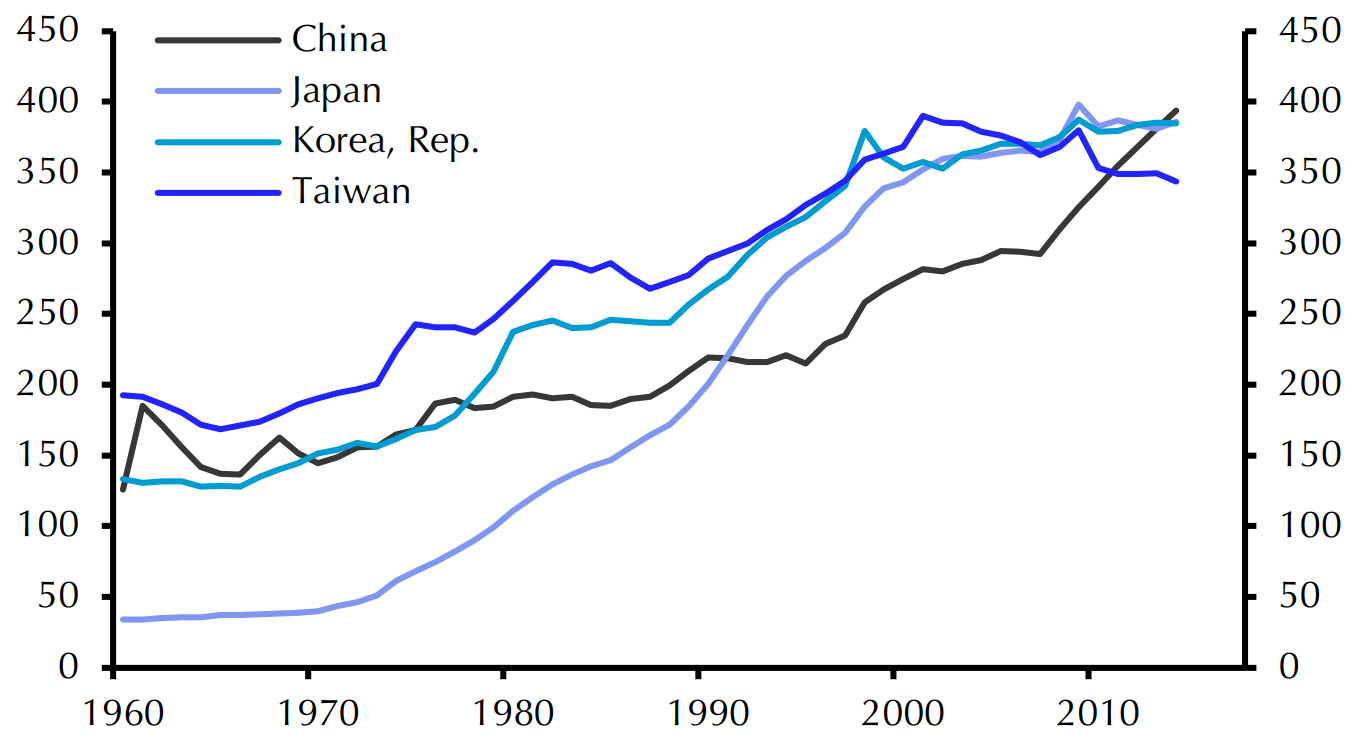

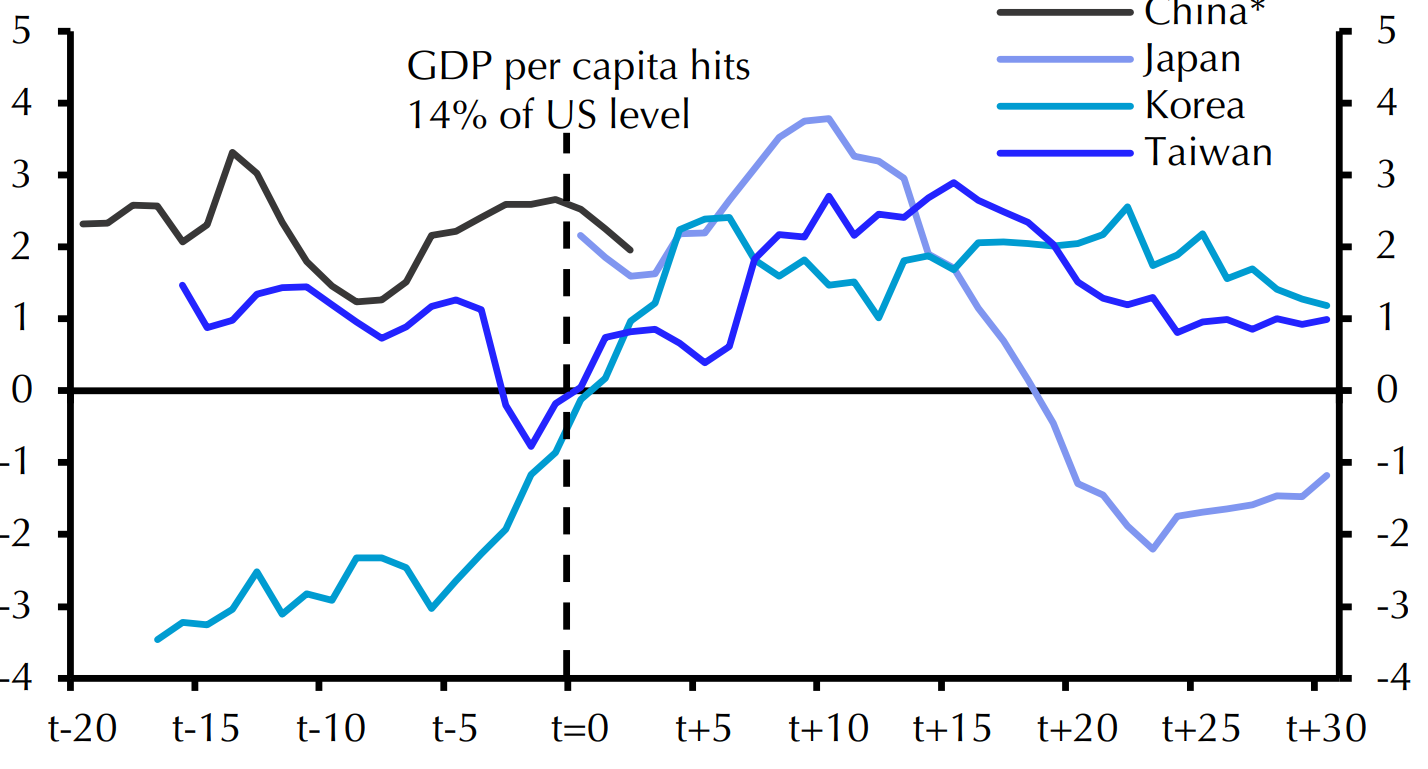

Once China reached these milestones, it followed a similar growth trajectory to its predecessors. Chart 2 compares income levels for major EMs in the 50 years before and after per capita income reached China’s current level relative to the US (14%). In the years before and after this income level was reached, the Asian successes were rapidly catching up with rich world incomes; China has been doing the same. But, as Chart 2 shows, this rapid catch-up is not the norm for emerging economies.

|

Chart 2: GDP per Capita (% of US level, current US$, log scale) |

|

|

*Russia, Brazil, Mexico, Thailand, Malaysia, South Africa, Turkey, Argentina Sources: World Bank, Penn World Table, Capital Economics |

Expectations are high

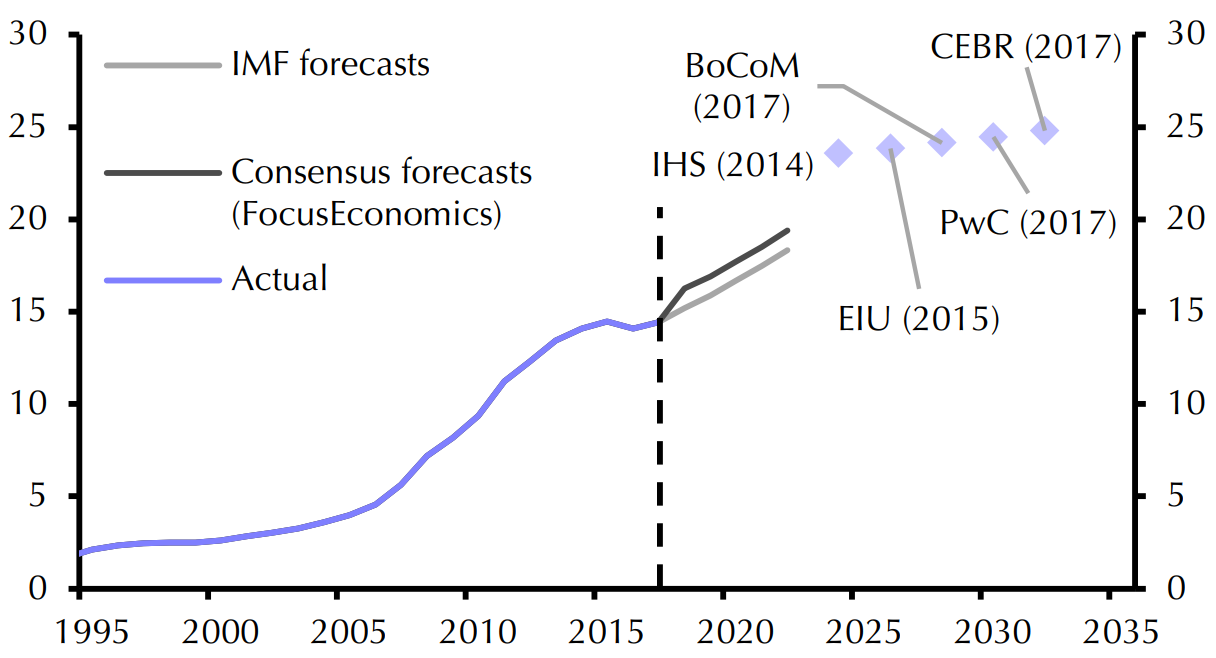

The consensus view is that China will continue to converge rapidly with the US. Chart 3 shows that both the IMF and private sector forecasters polled by FocusEconomics expect China’s per capita GDP levels to rise by another four to five percentage points relative to US levels during the coming five years.

These projections only go out to 2022. But we can get some sense of what’s expected further ahead by looking at public predictions for when China’s GDP will overtake the US at market exchange rates. We have used the UN’s medium fertility population projections to calculate the implicit per capita GDP ratios suggested by these predictions. These are shown by the diamonds in Chart 3, with labels indicating the name of the forecaster and the year in which the prediction was made.

|

Chart 3: GDP per Capita (% of US level, current US$) |

|

|

Sources: IMF, FocusEconomics, UN, IHS, BoCoM, EIU, PwC, CEBR, Capital Economics |

The consensus view seems to be that China’s per capita GDP will be around 10 percentage points higher relative to US levels in a decade’s time. This implicitly assumes that China can sustain the development path taken by Japan, Korea and Taiwan which all took roughly a decade to go from 14% to 24% of US levels. Is this plausible?

Investment-led growth reaching its limits

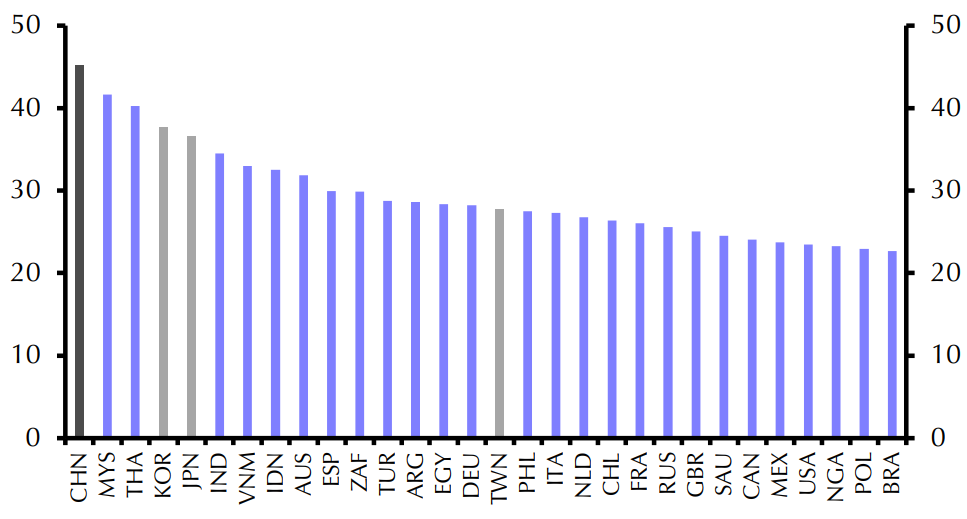

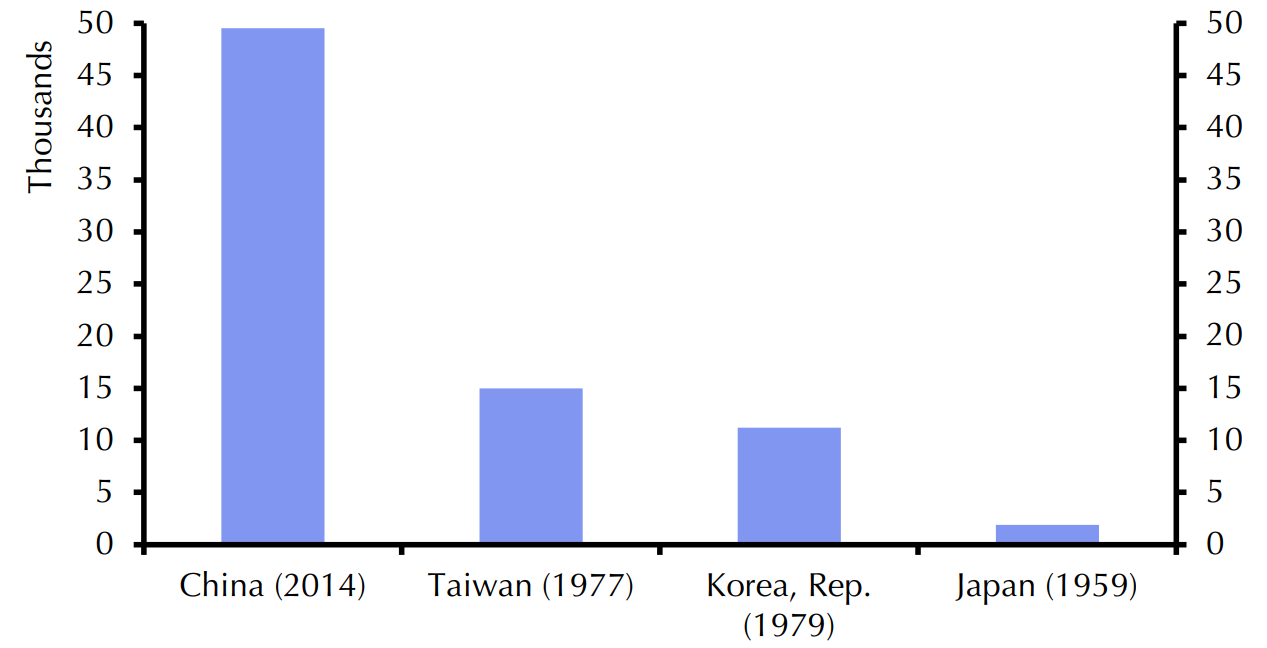

During the past decade, China’s economy has been reliant on investment to an unprecedented degree. Chart 4 shows the level at which the ratio of fixed capital formation to GDP peaked among all major economies (we look at a five-year average to smooth cyclical changes). In China’s case this was the period from 2010 to 2014, when the investment share averaged over 45%. It has since edged down slightly but remains above the peak levels seen elsewhere, including in Japan, Korea and Taiwan.

|

Chart 4: Peak 5-Year Ave. Investment Share of GDP (%) |

|

|

Notes – Investment refers to GFCF. Data covers period from 1960 to 2016. Sources: World Bank, Penn World Table, Capital Economics |

One consequence of China investing so much of its income over a long period is that it now has an unusually large capital stock for its income level. Most estimates place China’s capital stock per capita far above the equivalents for its neighbours at the same stage of development. (See Chart 5.)

|

Chart 5: Capital Stock Per Capita ($th, 2011 prices) |

|

|

Sources: Penn World Table, Capital Economics |

Some of this gap may be explained by technological changes that have made manufacturing more capital intensive in recent decades. But even by modern standards, China’s capital stock appears large. Its size relative to GDP has already matched current-day Japan, Korea and Taiwan. (See Chart 6.) And if China’s capital stock to GDP ratio were to continue to rise at the rapid pace of the past decade, it would soon be much higher than in other major economies.

|

Chart 6: Capital Stock (% of GDP) |

|

|

Sources: Penn World Table, Capital Economics |

All of this suggests that China has less scope to expand investment in the coming decades than its neighbours did when they were at China’s current income level. And even if China did somehow sustain rapid capital accumulation – perhaps thanks to repeated rounds of fiscal and monetary stimulus – it would do less to lift growth than in Japan, Taiwan and Korea. Our calculations suggest that China’s marginal product of capital – the amount of output generated by each additional unit of capital – has already fallen well below the levels that its neighbours achieved at the same stage of development.

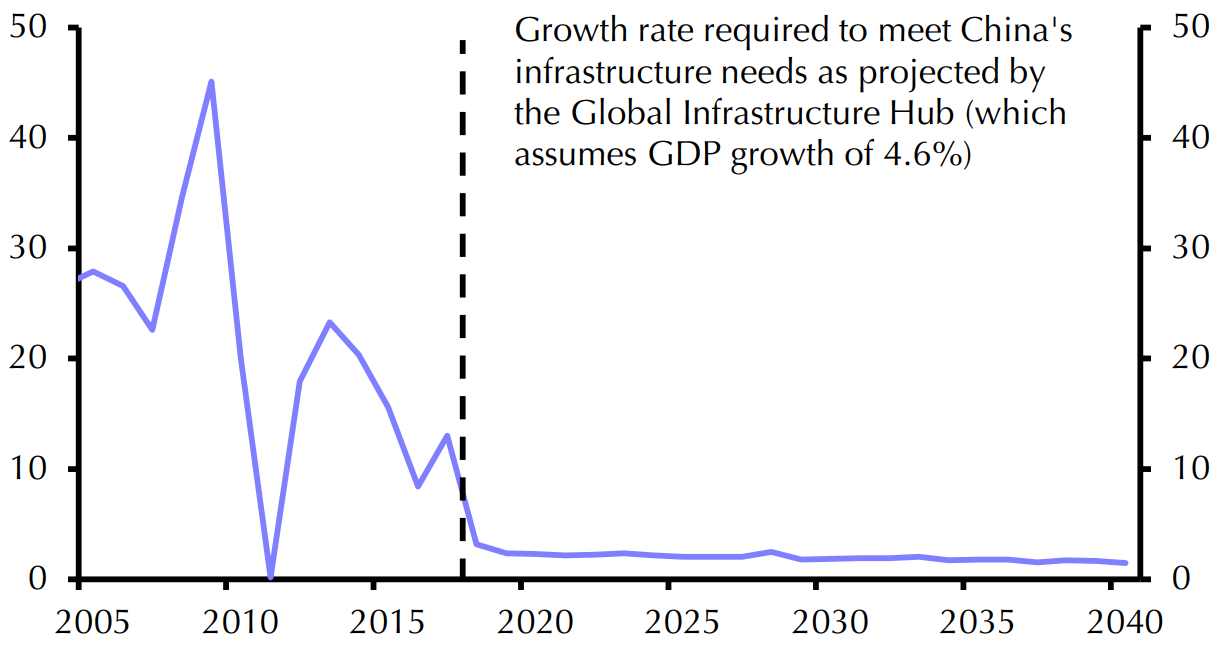

The growing constraints to investment are also visible at the sector level. Two decades of rapid spending by local governments have given China remarkably good infrastructure for a country at its income level. That’s not to say that there won’t be any need for additional infrastructure in future. But the rate of construction is likely to be much slower.

Indeed, the Global Infrastructure Hub (a G20 initiative) calculates that China’s sustainable pace of infrastructure investment growth has already declined to around 2-3% and will remain near this level for the foreseeable future. (See Chart 7.) The GIH is an initiative designed to boost infrastructure spending so these projections should, if anything, be optimistic on future infrastructure requirements.

|

Chart 7: Infrastructure Investment ($, % y/y) |

|

|

Sources: Global Infrastructure Hub, CEIC, Capital Economics |

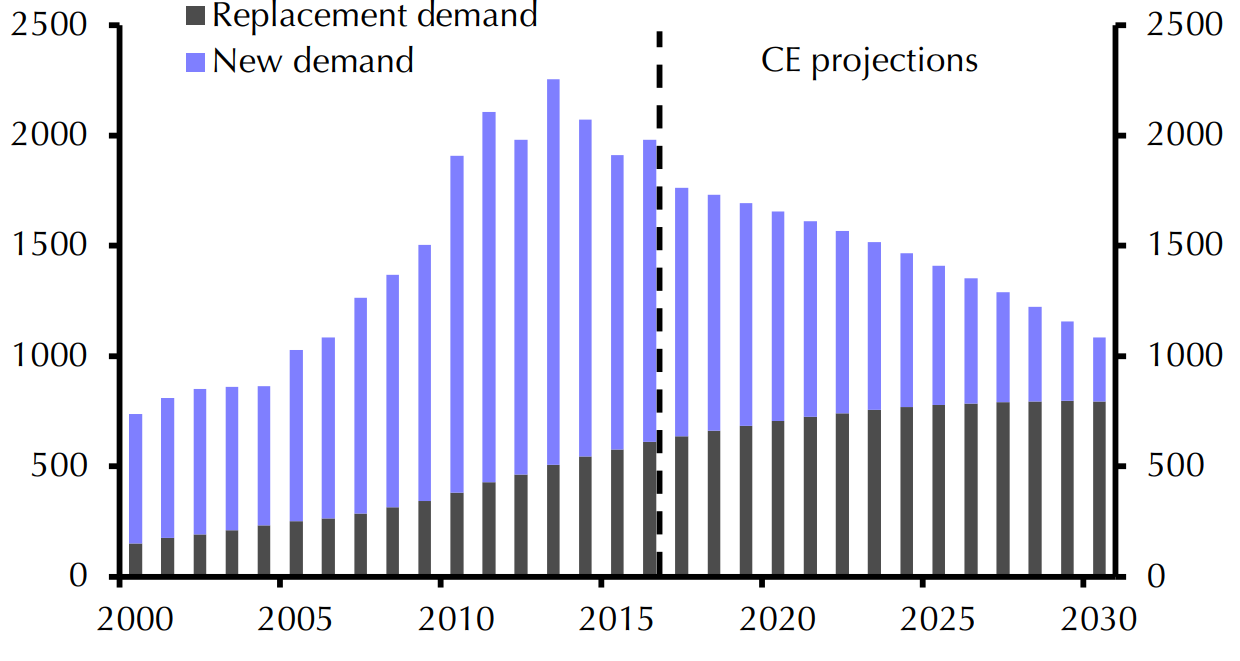

Similarly, underlying demand for new residential property is set to decline during the coming decade due to population aging and slowing rural-to-urban migration. (See Chart 8.)

|

Chart 8: Urban Housing Demand (sqm mn) |

|

|

Sources: CEIC, WIND, Capital Economics |

Residential property investment growth has already declined dramatically from a peak of 33% y/y in 2010 to 7% last year. But it is likely to slow even further during the coming decade given that developers will have little choice but to reduce the annual pace of new housing starts in response to the structural decline in demand. (For a detailed discussion of the outlook for residential investment please refer to our Property Handbook.)

Residential investment growth averaged more than 20% per year in both Japan and Korea in the decade after they reached China’s current income level. But our forecasts imply that, in China’s case, property construction won’t provide the same degree of support to economic growth during the coming decade. This partly reflects the large overhang of unsold homes that has yet to be fully absorbed by the Chinese property market. But it is also a by-product of slowing urbanisation and China’s less favourable demographics. During the coming decade, China’s urban population is projected by the UN to grow at less than half the rate seen in Japan and Korea at the same stage of development.

Finally, while its neighbours were still rapidly expanding the size of their manufacturing sectors to serve global demand, China’s sheer size means that if it were to add factories at the same pace over the coming decade, it would result in severe overcapacity that the world would be unable to absorb.

As Chart 9 shows, China’s current share of global exports is much higher than its neighbours’ shares were when they were at the same income level.

|

Chart 9: Exports (% of world total)* |

|

|

Sources: CEIC, Capital Economics |

In the decade after reaching China’s current income level, its neighbours averaged annual export growth of between 17% (Japan) and 30% (Taiwan). In the case of Japan, by far the largest of the three, this took its share of global exports from 2.9% (in 1959) to 5.8% (in 1969).

If China were to achieve 17% export growth in the coming ten years its share of the global export market would rise above 40% by 2027 (assuming global exports continued to expand at 4% per year).

This is of course implausible. Since 1950 no single country has captured more than a fifth of global exports. And even at its current market share of 13%, China is facing a push-back from trading partners who are threatening to erect barriers to imports of Chinese goods.

The risk of protectionism aside, China already has a very high market share in the goods in which it has a clear competitive advantage (consumer electronics for example), limiting the scope for further gains in these sectors.

Put another way, there simply isn’t enough demand in the world to sustain another decade of double-digit export growth from China. Indeed, it seems likely that in future China will gain market share much more slowly (if at all), with its exports expanding at a rate that is much more closely aligned with the global average.

This convergence process is already well underway. China’s export growth outpaced global export growth by nine percentage points on average in the 2000s but has only done so by four percentage points so far this decade.

From demographic dividend to demographic drag

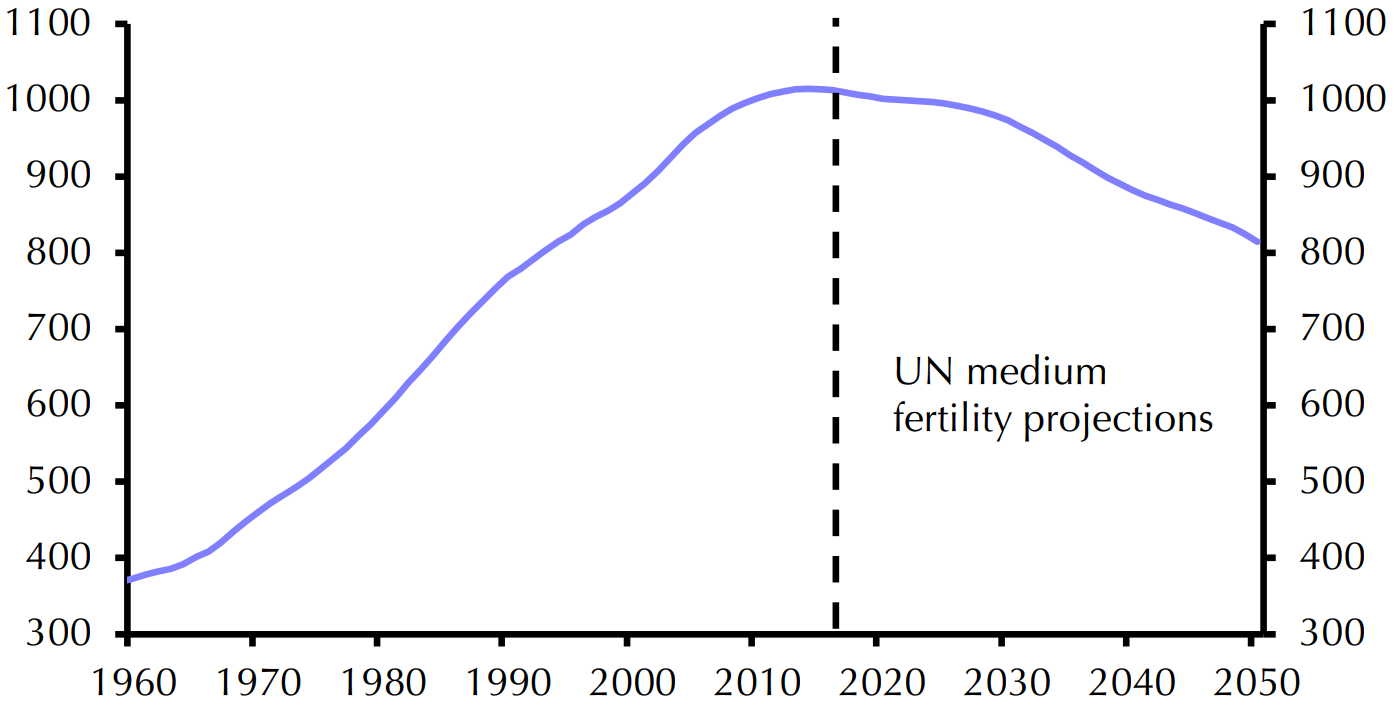

In addition to weaker investment growth, China’s economy is also set to face demographic headwinds from an aging population. China’s working age population peaked at the end of 2014 and has since started to edge down. The United Nations projects that this decline will accelerate during the coming decades. (See Chart 10.)

|

Chart 10: Working Age Population (15-64, mn) |

|

|

Sources: UN, Capital Economics |

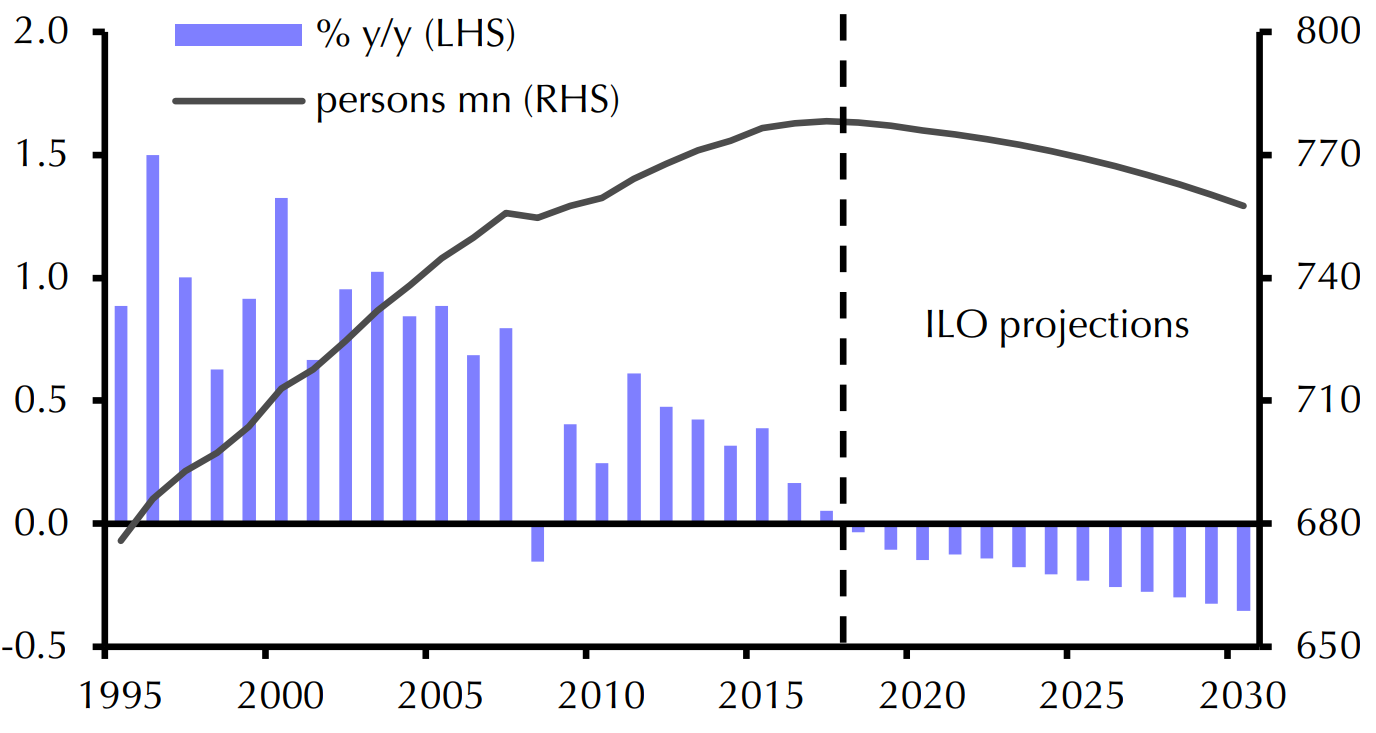

Employment growth has so far defied this downward trend. But this is unlikely to last. International Labour Organisation (ILOSTAT) projections suggest that employment could start contracting this year, with the drag on output growth rising to almost 0.5 percentage points by 2030. (See Chart 11.)

|

Chart 11: Employment |

|

|

Sources: ILOSTAT, CEIC, Capital Economics |

This demographic change will act as a drag both on overall economic growth and on the pace of per capita income gains as it pushes down the labour force participation rate.

Productivity growth to the rescue?

If China wants to sustain current growth rates in the face of slowing capital accumulation and an outright contraction in employment, it will need to boost productivity growth. Doing so won’t be easy.

Chart 12 shows growth in total factor productivity (TFP) – which captures fluctuations in output that aren’t due to changes in the size of the capital stock or workforce. It is not a perfect measure since it can be distorted by cyclical swings in the utilisation rates of capital. But averaged over many years it nonetheless provides some sense of how much of an economy’s increased output is due to technological progress, improved management techniques and better resource allocation, rather than simply adding more workers or machines.

|

Chart 12: Total Factor Productivity (% y/y, 10yr ave.) |

|

|

*based on our China Activity Proxy not official GDP Sources: CEIC, Conference Board, Capital Economics |

Average Chinese TFP growth during the past ten years has been roughly in line with what its neighbours achieved in the decade or two after reaching China’s current income level. As such, if China is to match their growth performance going forward, in spite of greater headwinds from slowing investment and population aging, it will need to raise TFP growth, probably to at least 3%.

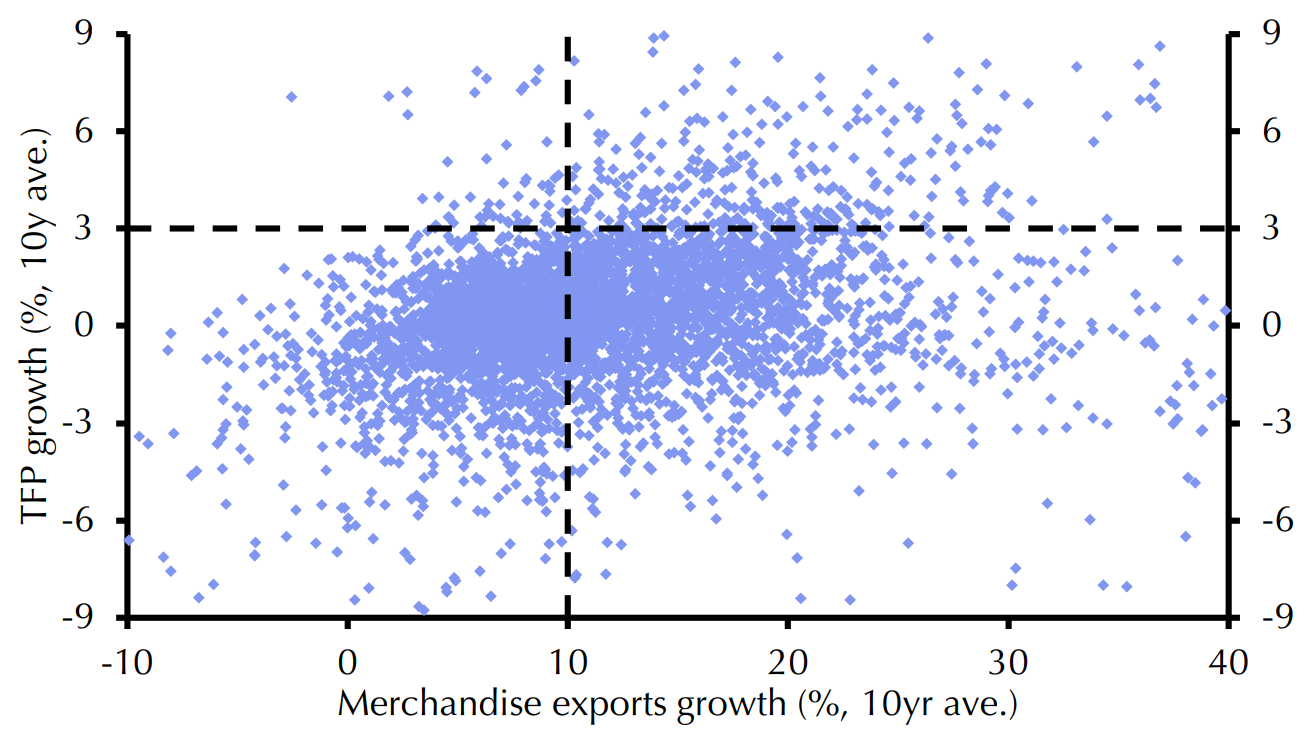

Such rapid TFP growth is not unheard of but has historically been rare and nearly always coincided with double-digit export growth. Chart 13 illustrates this by plotting average TFP growth against average export growth over ten year periods since 1960 for every country in the Conference Board Total Economy Database. Only a handful of countries have ever generated rapid TFP growth without also experiencing double-digit export growth. Such episodes are so rare that they make up only 1.2% of the observations in Chart 13. On average, productivity growth spurts of 3% y/y or more over a decade coincided with exports expanding at 20% y/y over the same period.

|

Chart 13: TFP Growth vs Export Growth |

|

|

Sources: World Bank, Conference Board, Capital Economics |

This relationship makes intuitive sense. The ability to tap global demand and competition with global firms provide a strong incentive to raise productivity. And exposure to global competition is itself a powerful catalyst for diffusion of technology.

In practice, this relationship means that we should either expect China to sustain both the double-digit export growth and rapid TFP growth that its neighbours achieved or we should expect it to sustain neither.

We have already discussed why China’s sheer size and already-high global export market share make it very unlikely that double-digit export growth can be sustained. If we are right, TFP growth seems more likely to slow than accelerate. Not only will slower growth in global demand for Chinese exports weigh on the pace of capital accumulation in manufacturing, it will also result in less impetus to squeeze more production out of existing capital.

In search of a new growth model

The upshot of what we’ve discussed so far is that the model of rapid export growth and investment growth that was still propelling Japan, Korea and Taiwan towards high income when they were in China’s current position no longer fits China’s circumstances. And there is little that policymakers can do about it since this reflects past decisions and structural factors they cannot change: the intensity of investment over the past couple of decades, unfavourable demographics and the country’s sheer size.

In turn, we believe it highly unlikely that China will follow the path that its neighbours took as they converged with the developed world.

It is possible that China might instead follow a unique “Chinese model” of development that will set it on an equally impressive growth trajectory via other means. But this has no historical precedent and so it seems a stretch to argue that this is the most likely outcome.

In any case, the current trajectory of policymaking in China seems more likely to hinder than help future growth.

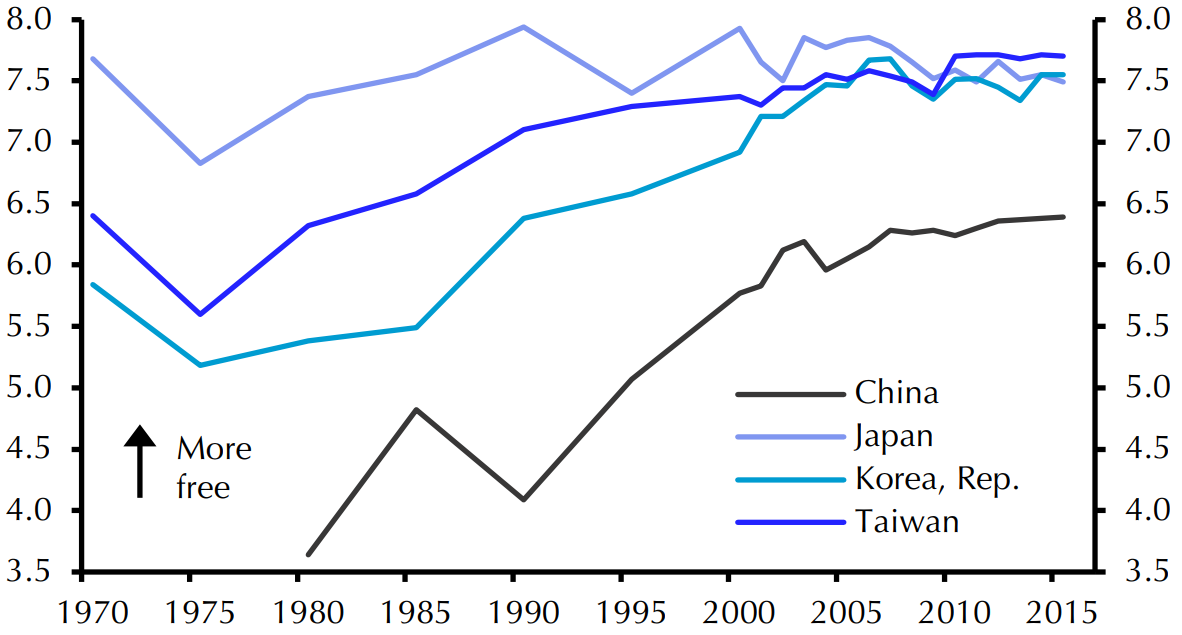

Aside from their export performance, one reason that Japan, Korea and Taiwan sustained rapid growth beyond China’s current income level is that they continued to liberalise their economies. Chart 14 illustrates this using an index published by the Fraser Institute measuring economic freedom.

|

Chart 14: Fraser Institute – Economic Freedom Index |

|

|

Sources: Fraser Institute, Capital Economics |

Economic liberalisation was also a key driver behind China’s rapid growth during the 80s, 90s and 2000s. However, as Chart 14 illustrates, liberalisation has largely stalled during the past decade. Progress has still been made in some areas – the most obvious being the opening up of the financial sector. But in other crucial areas, such as the ability of firms to operate without political interference, things are moving backwards.

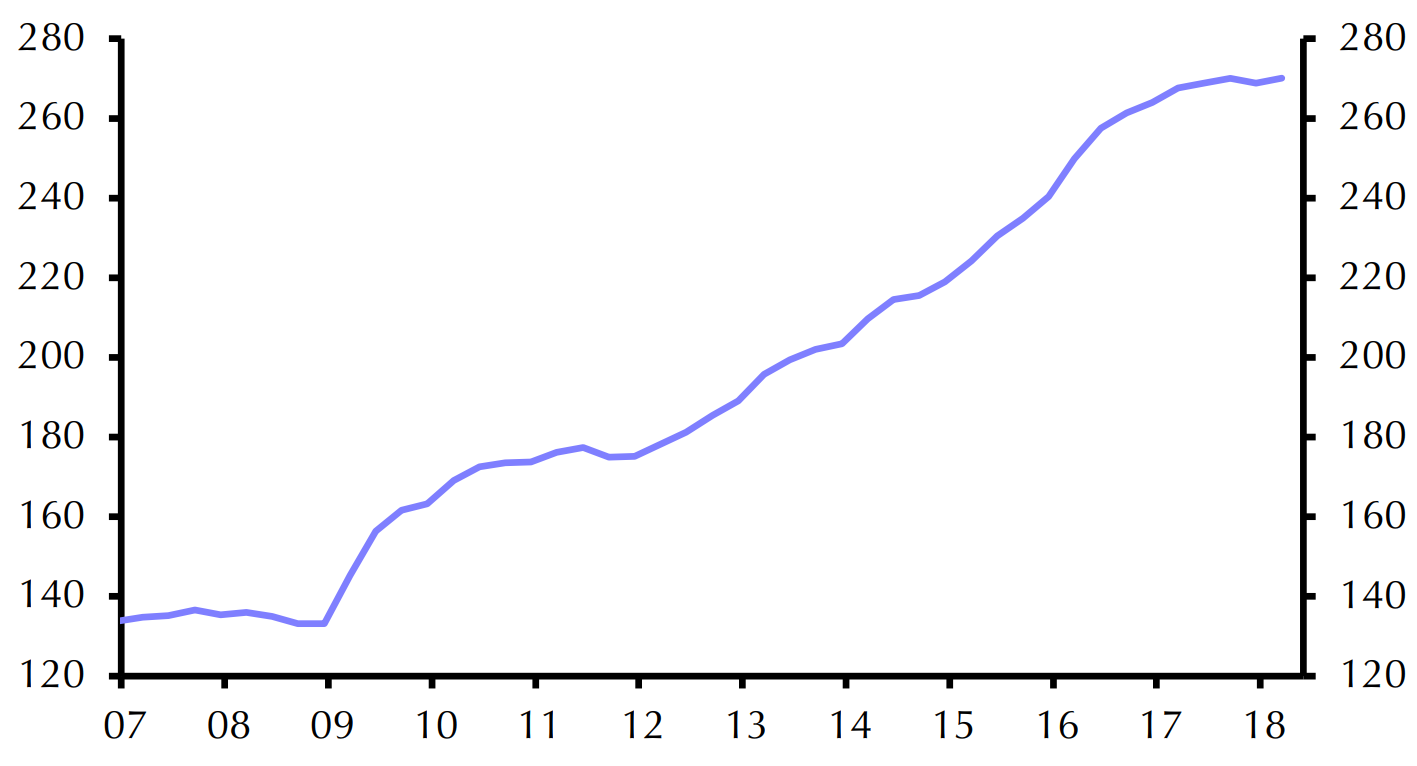

It is not hard to find evidence that state intervention is causing a widespread misallocation of resources. The most widely acknowledged sign of this is the surge in the debt ratio during the past decade. (See Chart 15.) New credit is not generating equivalent increases in output because banks and other lenders would rather lend to inefficient state firms than their more efficient private counterparts since the former benefit from implicit government backing.

|

Chart 15: Credit To Non-Financial Sector (% of GDP) |

|

|

Sources: CEIC, Capital Economics |

Admittedly, the debt to GDP ratio has levelled off recently, which some are taking as a sign that credit allocation is now improving. But a more convincing explanation is simply that the latest round of policy stimulus led to a temporary jump in nominal GDP growth. With the impact of this stimulus now starting to fade, we think it is only a matter of time before the debt ratio begins to climb again.

The surge in Chinese debt levels is a key risk to the economic outlook that has been widely discussed. Every other major emerging market that has witnessed such a large increase in debt ratios over such a short time horizon has subsequently faced a banking or financial crisis of some sort, with economic growth suffering in the aftermath.

Although many indebted firms in China have been given a temporary reprieve by the latest round of policy stimulus, they may run into trouble in the coming years if, as we expect, the economy resumes its slowdown. And with policymakers still hopeful that the market will be able to absorb the costs of the debt clean-up via NPL securitisation and debt-to-equity swaps, there is a risk that they will fail to intervene in time to avert a bout of financial instability.

At the same time, China has a unique degree of control over its financial system since nearly all of the major lenders are state-owned. And it seems very likely that, when push comes to shove, the government will step in forcefully to back-stop the financial system in order to prevent any volatility from snowballing into a full blown crisis – taking much of the bad debt on to its own balance sheet if necessary. This would push up China’s government debt ratio considerably. But for a country with sovereign monetary policy this shouldn’t pose too much of a problem.

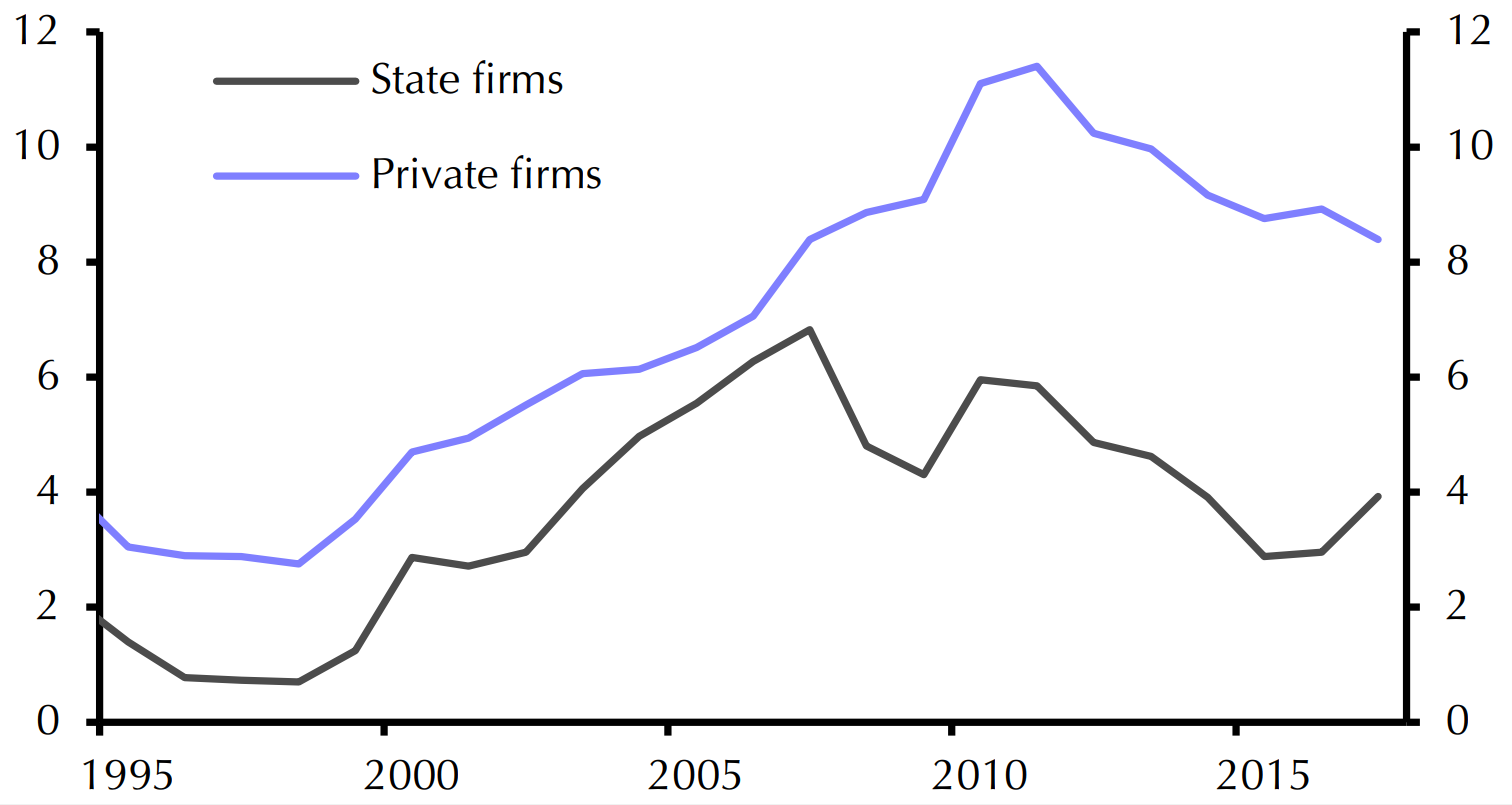

The broader issue, however, is that even if a credit crisis can be avoided, poor resource allocation still comes at a cost in that it undermines productivity growth. The evidence for this is clearest in industry where private firms generate a far higher return on their assets than state firms do. Chart 16 shows this for industry as whole, but private firms also outperform their state counterparts in every individual sector in which they compete.

|

Chart 16: Return on Assets of Industrial Firms (%) |

|

|

Sources: CEIC, Capital Economics |

But the problem isn’t limited to the state sector. If it were, it would still be manageable since state firms make up only a small part of the economy, employing less than 15% of non-agricultural workers.

State intervention has much broader repercussions. It includes industrial plans that steer resources to designated sectors, and as private firms get bigger they increasingly have to fall into line with what officials want them to do. Get to a certain size and companies have to give as much thought to meeting the needs of officials as those of consumers.

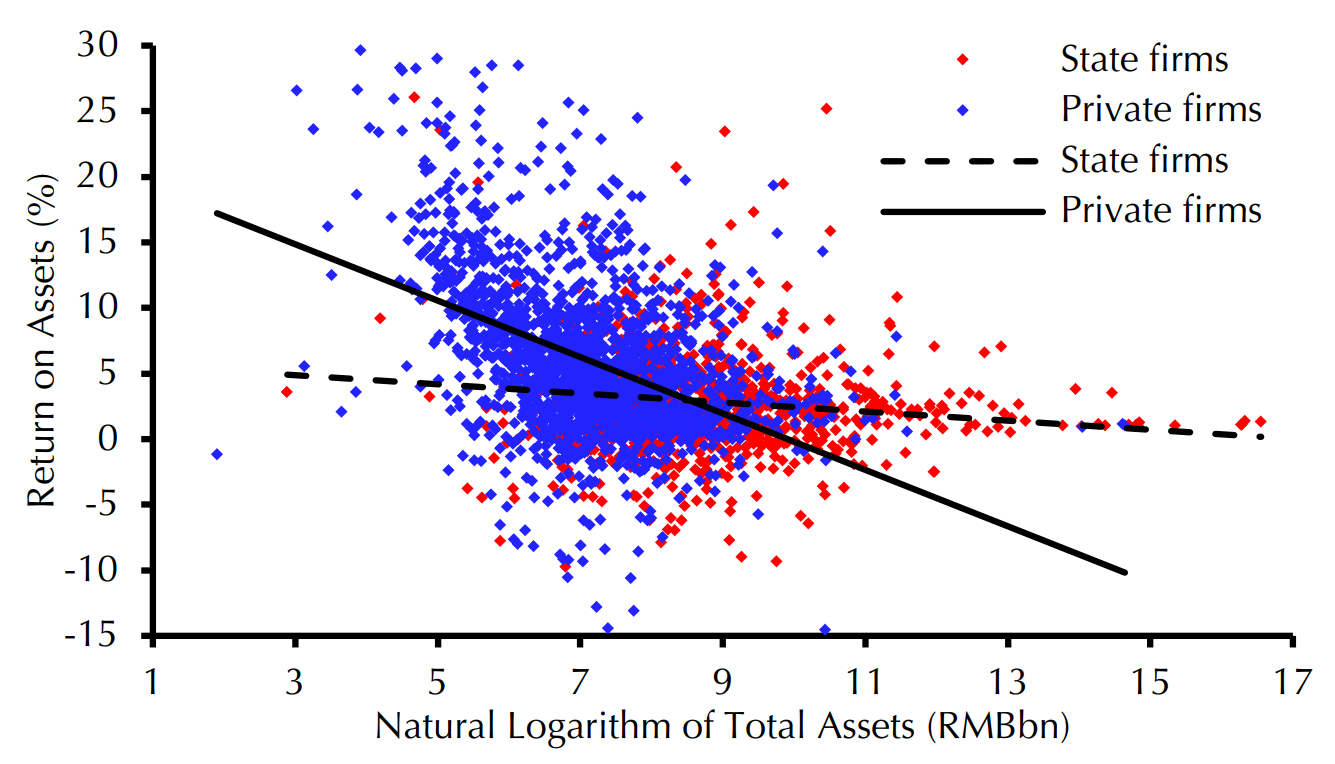

In most countries, large firms generate a higher return on assets on average than small firms do thanks to economies of scale that allow for more efficient operations. But in China’s case the reverse happens. Chart 17 plots the five-year average return on assets for all listed firms in China against their size, as measured by the total value of their assets. The firms have also been separated into two groups depending on whether they are state-owned or privately owned.

For both groups, firm size is negatively correlated with performance. However, the relationship is much stronger among private firms. We suspect that this is because all state firms, regardless of their size, are subject to some degree of political interference but private firms only become targets for politicians and regulators once they reach a certain size. In other words, political interference appears to be weighing on the performance of all large firms, regardless of whether they are state-owned or privately-owned.

|

Chart 17: Return on Assets of Listed Firms (2012-16 ave.) |

|

|

Sources: Bloomberg, Capital Economics |

The upshot is that in order for us to be optimistic on the prospects for future productivity growth in China, we’d have to believe that Chinese policymakers were going to give the market freer rein.

Unfortunately, there are few signs that Xi Jinping intends to row back state intervention. Instead, he appears to have concluded that maintaining state control over large swathes of the economy is crucial to the Communist Party keeping political control of the country.

What does this all mean for the growth outlook?

The upshot is that the underpinnings of China’s growth outperformance over recent decades no longer look secure. Investment is running into diminishing returns. Demographics are becoming a headwind. And the direction that the Party leadership is steering the economy in is likely to result in slower productivity growth in future. None of that necessarily means that China is in deep trouble. But it does make it increasingly unlikely that China can continue to outperform.

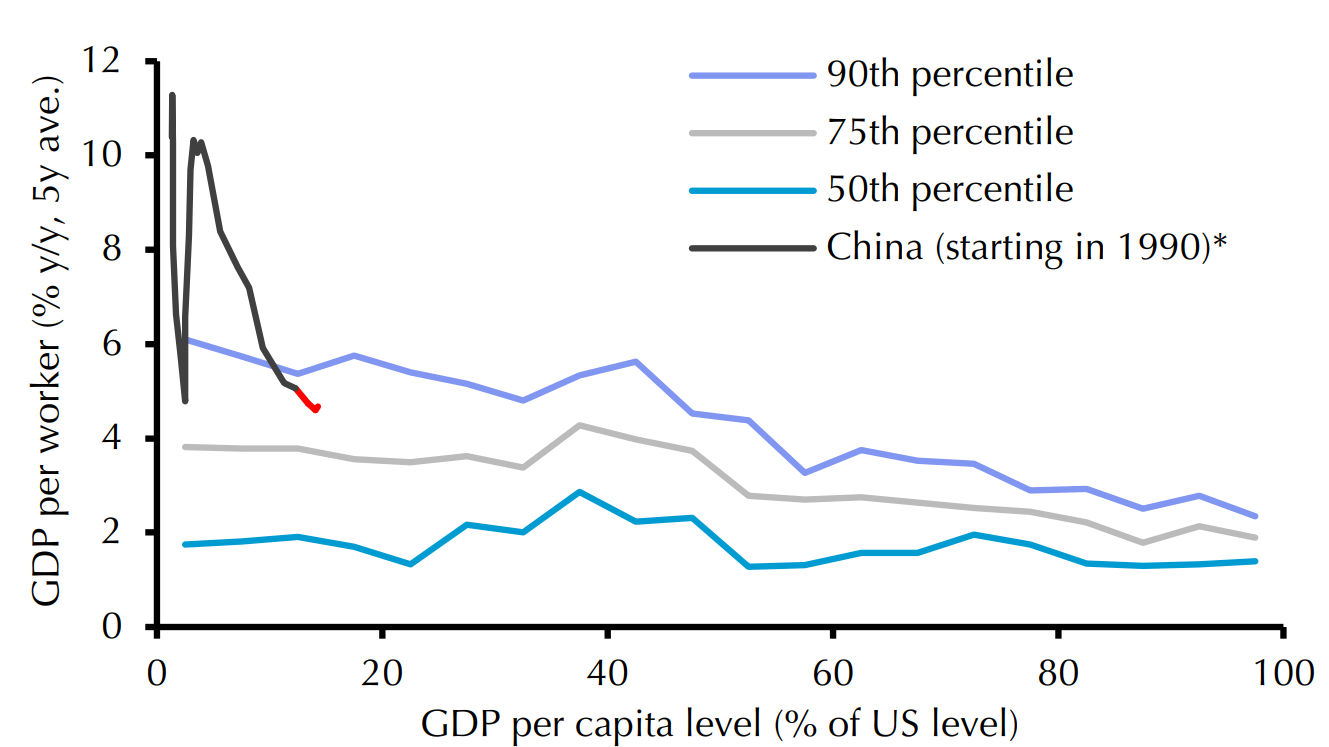

Chart 18 plots China’s growth in real output per worker, including our forecasts up to end-2020. We have benchmarked China’s performance against what has been achieved by all economies in the World Bank database (plus Taiwan) for every five year period between 1960 and 2016.

We use our China Activity Proxy (CAP) to derive the China series here rather than the official GDP series. The CAP has recently suggested that the official figures are overstating China’s growth. Even so, China has been a very strong performer over the past five years, with output per worker growing faster than in three quarters of economies at the same income level through history. But the scale of China’s outperformance has been sliding. We expect this reversion towards the mean to continue.

|

Chart 18: Labour Productivity Growth vs Income Level |

|

|

*Based on the CAP, CE forecasts up to 2020 shown in red Sources: World Bank, Penn World Table, CEIC, Capital Economics |

If anything, it will become increasingly hard for China’s outperformance relative to the EM average to continue over the next decade. Constraints on investment will intensify as unfavourable demographics and slowing urbanisation weigh on demand for property and infrastructure. The difficulties of further raising an already high market share of global exports will grow.

Meanwhile, although state intervention is not a new development, the costs are likely to be higher in future. For economic planners able to mobilise capital, it is relatively simple to allocate investment effectively in a country that is poor: many investments will generate sizeable returns. It becomes much harder to identify productive investments as countries move up the value chain and toward the technological frontier. It is no coincidence that, a few commodity-rich economies aside, the countries that have successfully reached high income status all rely on the free market to allocate resources to a degree that China seems reluctant to embrace.

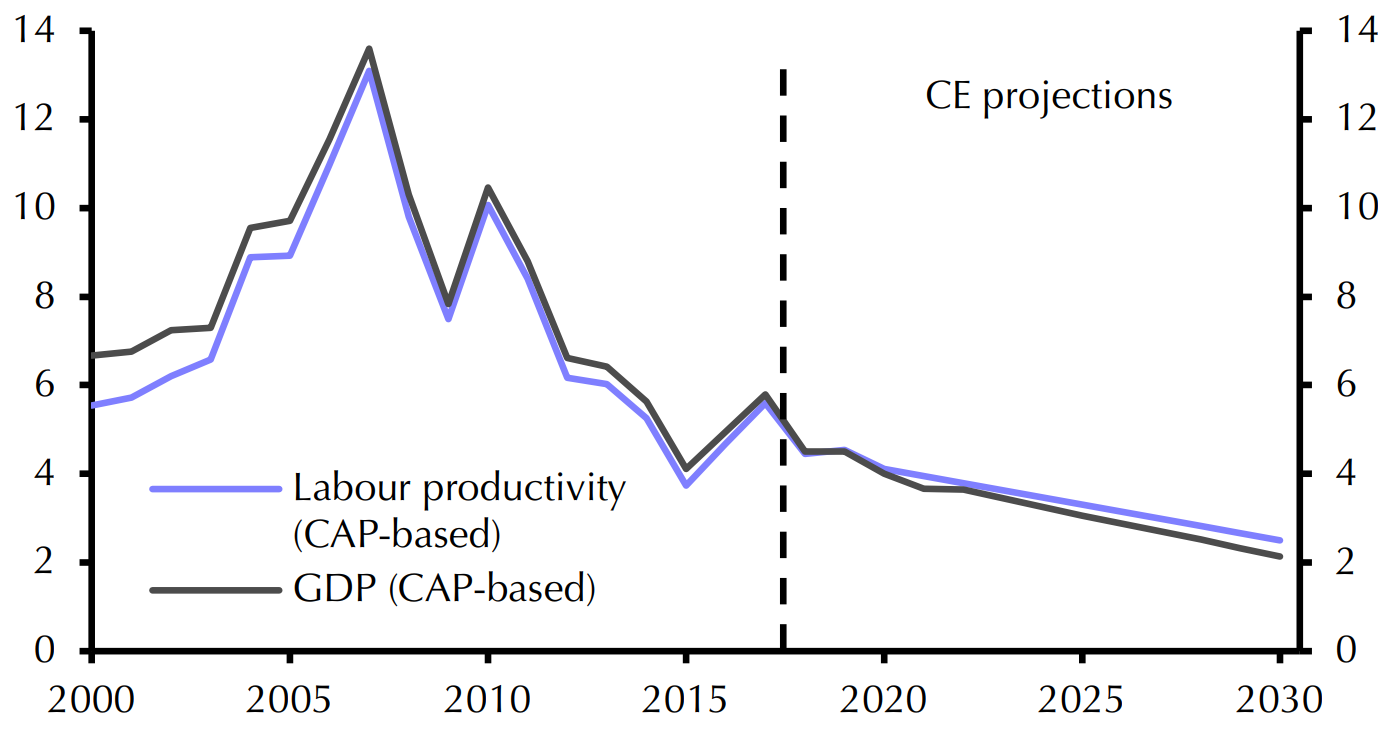

|

Chart 19: Labour Productivity & GDP (% y/y) |

|

|

Sources: CEIC, ILOSTAT, Capital Economics |

In sum, unless there is a major shift in the reform agenda, China’s labour productivity growth will probably continue to converge with that of the average EM during the coming decade. That would take it to around 2.5% by 2030. ILOSTAT projections suggest that the drag to total output growth from declining employment will have risen to roughly half a percentage point by that stage. Therefore, if we are right that China’s long period of economic outperformance is coming to an end, the sustainable growth rate of its economy will slow from around 4.5~5.0% now to around 2.0% by the end of next decade. (See Chart 19.)

Julian Evans-Pritchard, Senior China Economist, +65 6595 1513, julian.evans-pritchard@capitaleconomics.com

Mark Williams, Chief Asia Economist, +44 20 7811 3903, mark.williams@capitaleconomics.com