Plus, speculation about Fed rate cuts took hold in Q4 last year and equities prices surged. Then policymakers pushed back on those expectations coming into 2024 – and prices have still surged. As a bubble forms in the market, Markets Economist James Reilly explains what’s driving stocks as hopes for policy easing ebbs and flows, how stocks could respond when the Fed finally does cut rates and what a Trump re-election could mean for the market.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 8th of March and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, the Fed and the US stock market bubble. But first, Neil Shearing is out this week, but I'm happy to say we've got a special guest in the shape of Mark Williams, our Chief Asia Economist. How's it going, Mark?

Mark Williams

Very well, David. Pleasure to be here. Thanks for having me on.

David Wilder

Thanks for joining. Have you been gripped by the minute to minute proceedings of the National People's Congress in China this week?

Mark Williams

Always gripping, very sad there won't be a closing press conference from their Premier. That was always one of the highlights of my year.

David Wilder

Yeah, very telling about a changed mood in Beijing. So, I think delegates at the NPC should be spending less time at the moment studying the work reports and rereading 'The Governance of China' by Xi Jinping and more time reading your new report about the coming crisis in construction. It answers a big puzzle in the market about why commodities demand has held up, even though the property industry is in crisis. Talk about that puzzle. Talk about your findings.

Mark Williams

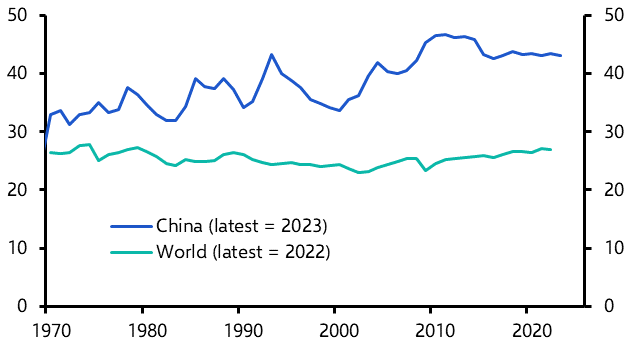

Yes. So this has been a puzzle that we've been discussing, particularly with our clients in the commodity area, for the past year or so. So essentially, as everybody knows, China's property sector was in crisis. These three red lines were introduced to limit financing to developers back in 2020. Since that happened, the sales of residential property in China have halved. The starts of new residential property projects have fallen by two thirds. And when we look at financial markets, prices of developer bonds are down by 70%. Developer equities are down by 80%.

So it's a real bloodbath out there. But then when you look at the output of the stuff that goes into building property, well, you just can't see it really. So within China, the output of steel products and China's import of iron ore is roughly the same now as when those three red lines were introduced. And given that about a third of steel in China goes into property construction, that's a real puzzle. Other inputs really look at things like the output of glass, sheet glass, plate glass going into windows. That's higher now than it was when the three red lines were introduced. So that's the puzzle. Everything looks terrible in the property sector, except for the production and imports of the stuff that actually goes into making property. And we think that we have an answer to that puzzle, which is that digging into the data, we think that a lot of the things that most people are looking at as gauges of what's going on in property in China are missing a big part of the picture. Because what most of us look at month to month to tell us how much activity is happening is based on a survey of Chinese property developers.

That's not the whole story. There's a whole load of property construction that happens in China that is not done by property developers. Things like the construction of social housing by the government or construction of housing outside of the urban areas. When we looked into that, we found that actually it looks like property construction is holding up pretty well. That explains why steel products production is out, why iron ore imports are doing okay, why glass production is doing okay. That of course, though, just creates another puzzle. Why is it then that property construction is doing so well if everything else is collapsing? I think really what's happened is that partly the government has been pushing developers to complete ongoing projects. And so although they're not starting any new ones, they are still quite busy completing existing ones. And meanwhile, the government is also putting more money into building social housing so as to sort of mop up some spare capacity in the construction side and keep employment high there. So that's what's been going on. As a result of this, somewhat incredibly, the amount of property that is being constructed right now in China, if we look at it in terms of square meters, the simple area of property that is being constructed right now in China, is actually higher today than it was at the moment when the three red lines were announced in 2020. So we've had this colossal property crisis in China, and yet there's more property being built right now than there was when it began.

David Wilder

But your report does make this point that a lot of this construction does seem to be on borrowed time, doesn't it?

Mark Williams

Yeah. I mean, the underlying problem, the thing really which is the trigger for the initial crisis was the fact that the demographics for China give a really bad outlook for the property sector. So, I mean, we published some projections a few years ago, I think back in 2017, saying that by 2030, the amount of new property that would need to be built each year in China would be half of what it was in 2020. So, halving of residential construction activity. Interestingly, the IMF just last month, they put out a report which came to essentially the same conclusion that China is going to be needing roughly half as much property at the end of this decade as it is around now, kind of early on in this decade. Because, primarily because of the demographics, because the population is no longer growing, urbanization has really slowed to a crawl. And also there's less need now in China to rebuild old areas, old urban areas, because there's been a huge wave of urban renewal over the past 10 or 15 years. So that's the underlying problem for the property sector. And I think a lot of people had assumed that that correction was well underway with nearly four years into this property crisis. But what our study is suggesting is that actually in terms of construction activity, that correction really hasn't begun yet. That all lies ahead of us. So there's still a lot of downside to come in terms of things like China's demand for the inputs into construction, things like iron ore, in terms of employment as well in the construction sector. So sadly, we have had discussions a lot over the past six months or so about how soon can we start to think that this property crisis might be over? When could China start to pull itself out of the property crisis? But what our analysis is telling us is that there's a long way still to go.

David Wilder

Talk about the shape of this correction, because it kind of sounds in some respects like sort of Wile E. Coyote moment where he's gone over the cliff, his legs are still in motion in midair and it's just a moment before he goes plummeting to the ground. Is that kind of what we're looking at given what we've seen on the sales and start side? I mean, how does this all play out? And what does it mean for the economy?

Mark Williams

So we're looking at a 50 % fall in residential construction activity, we think, over the not too distant future. Now exactly how quickly that pans out, it's hard to say. As you say, there is a bit of a Wile E. Coyote element to this. And I think that China's policymakers, they probably do have some room still to keep Wile E. Coyote in the air by continuing to invest more in social housing and things like this. But that's not a solution. That's just a short-term fix because the demand is what the demand is. There will be fewer people losing housing in future than today. We've looked at other countries that have seen similar downturns and somewhat to my surprise, 50 % falls in residential construction activity and not actually that unusual. So looking across the OECD, so that's what 38 rich and middle income economies around the world we found 18 occasions or 18 countries that have experienced a 50 % fall in residential construction over relatively short periods in the past. And typically those declines take about three or four years to materialize. Now in China's case, because of the government's ability to keep funneling resources into things like social housing, we think that they'll be able to slow the decline. And so we've sort of assumed that it will take maybe to the end of the decade, so seven years, twice as long as it does in the typical OECD economy for this 50 % fall to materialize. That would still mean though, that on average across that seven -year period for the rest of this decade, we're still looking at GDP growth being about one percentage point lower than it is today. So we've already seen that because property has stopped growing in China, that's removed the boost that property used to give China's GDP growth. It used to give a boost of about one and a half percentage points each year. That's gone. That's the slowdown we've seen so far. But what we're expecting is another one percentage point off today's growth rate over on average over the rest of this decade. That's assuming it takes seven years to materialize. If we're wrong about that and it follows the pattern that we've seen in other economies and just takes three or four years, then we could be seeing a much bigger drag on China's GDP growth.

David Wilder

It's hard to understate just how big property construction has been as a driver of China's economy. I think your report notes two-thirds of overall construction activity has been in property. So given what you've just said about the hit to GDP growth, the government has this reputation of pulling on the stimulus levers when growth disappoints. Used to pull on the property sector stimulus lever to boost growth. Where does that leave them? Is it now all infrastructure all the time?

Mark Wlliams

We've seen over the past two or three years that there has clearly been a push into investment in other sectors. So a lot of people have highlighted the push into high -tech manufacturing. That's definitely real. But more generally, manufacturing has got more investment. And as you say, infrastructure has got... Essentially, investment has been growing pretty strongly in lots of sectors other than the new flow into property. But it's hard to see this really as something which can offset the scale of the weakness that we're seeing from property. And that's for a couple of reasons. One is simply, as you say, the property sector is so big in China. Just property construction alone generated about 13 % of China's GDP last year. That's huge. And that's not taking into account other services that are associated with real estate. So it's very hard to offset that by boosting other parts of the economy. And then the other constraint is as you've talked about on this podcast before with Neil, that if this investment is going into manufacturing, then where is all of the output for manufacturing going to go ultimately? China already has its share of global exports is already an all -time high starting right now. So if we're going to pour more investment into manufacturing, that's presumably still going to lead to more stuff being shipped abroad, but who's going to buy it? Who's going to buy it?

We're already seeing pushback from the US, but also from Europe about the competitive threat that is coming from China's manufacturing sector. And of course, the push into higher value -added manufacturing, into high -end manufacturing, which is something that again, the government in China has been stressing this week at the National People's Congress, is now talking about something called new productive forces, which is putting more emphasis on high -end technology, high-end manufacturing.

That really brings Chinese firms much more directly into competition with firms in the rich world. So wealthy governments may during the 2000s have not minded too much as they saw a flood of relatively low end imports into their economies, which has brought down prices for consumers. Everybody felt a bit better off, but it's, I think, a very different story if it's the European car industry that is facing the brunt of Chinese competition.

David Wilder

This all feeds into that reform question, doesn't it? Because one of the answers here is that more efforts are made to stimulate domestic demand, increase consumption, reduce investment as a driver of growth. You mentioned the MPC that's going on in Beijing at the moment. As usual, there's been this focus on near -term growth targets and the like, but have you and the China team picked up any signals about longer-term plans? You're painting this fairly grim take on China's economic future, but the rhetoric coming out of Beijing doesn't seem to suggest as much urgency on the part of officials, does it?

Mark Williams

No, it doesn't. And I think there's a couple of reasons for that. One is, I think that the officials, to some extent, are maybe underappreciating the extent of the headwinds that lie ahead. I think that they're going to be surprised, as they have been surprised over the past few years by the headwinds that are facing China's economy. And we're seeing that in terms of the fallout from decades of very rapid investment, and particularly in the property sector, we're seeing that chicken coming home to roost, but also in areas like demographics, where the official projections for what would happen to the birth rate have repeatedly been over optimistic. And so I think that officials are still too optimistic about what will happen next.

I think there is a second element to this, which is certainly relative to where we were 10 or 15 years ago. The government is much less focused these days on economic growth as a marker of its success. It used to be that it was all important really, the rate of growth across the country, officials would be promoted or demoted depending on how successful they were in achieving rapid growth in their areas. That's no longer the case. We are seeing for example, environmental targets, energy intensity targets. We've got a target from the NPC of reducing the energy intensity of output by around two and a half percent this year. So there's other considerations as well. And then the most important of those other considerations is national security. And that's clearly at the heart of a lot of policy where it's really important to China's leadership that China is more resilient, is less dependent on foreign inputs, foreign technology in key areas. And that I think is the priority rather than just focusing on what headline growth is going to be. So that's a big change. I think that everything else equal, the leadership would like to have faster growth than it's seeing, but I think that it's willing to tolerate a slower growth than it would have been in the past because that's no longer his priority.

David Wilder

Mark Williams there on the coming collapse of Chinese construction. I'll add his report to the podcast page - it's an eye opener - along with some analysis from the National People's Congress and the team's assessment of China's reform progress. The coming week's events include US inflation and UK labour market data on Tuesday and then UK GDP data on Wednesday. Our US team is expecting that February CPI report to show more evidence of cooling core inflation. On the UK data, our economists think wage growth is cooling, even though it may not show up in the Tuesday release. They're also forecasting that Wednesday's release will show that GDP rose 0 .2 % month on month in January. If confirmed, that would point to the recession at the end of last year already being over. Also on Wednesday, the team will be holding a Drop-In, that's one of our short-form online briefings, all about the UK general election. They'll be talking about the fiscal constraints, but also the global challenges that await the next government. That's 3pm London, 11am New York. I'll put details about that on the podcast page, along with their report, analysing the post-election economic landscape. There's also a preview briefing in the coming week of Russia's presidential election, which starts on Friday.

Now the outcome of this election may be a bit more predictable than the UK's, but it's throwing up lots of questions from the economic sustainability of Vladimir Putin's war with Ukraine to what happens when Mr Putin finally leaves office. Liam Peach from our EM team has a big report out which looks at all of these issues and more, and he'll be online on Tuesday at 11am New York, 3pm London to address them. Again, details on the podcast page. And then just after that briefing is a session all about the global commercial real estate recovery. Chief Property Economist Andrew Burrell thinks it's going to be the slowest on record. Sign up for that session to learn more about Andrew's forecasts and to ask your questions. That's 11 .30am New York, 3 .30 London on Tuesday. Details of all of our events can be found on our events page, capitaleconomics.com/events, where you can also watch recordings of previous sessions.

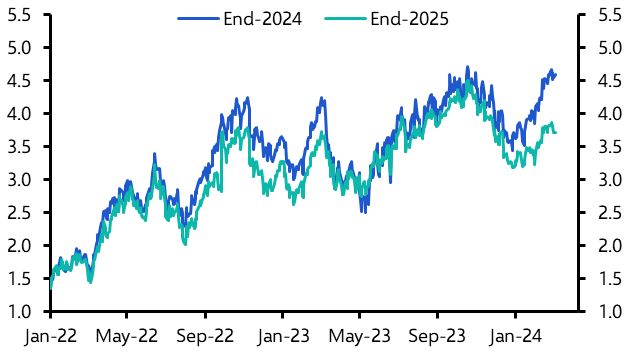

Don't forget, if you're a CE Advance subscriber you get access to all our events and all of the underlying data as well as tools to engage directly with our Economist team. Now, the S&P 500 has risen nearly 9% this year as of this recording, even though expectations for the first rate cuts from the Fed have been pushed into the backend of the second quarter and the volume of cuts anticipated over 2024 has been slashed.

It's striking that a rebound in US equities that was triggered by dovish signals from the Fed last October hasn't faltered, even though officials have been damping down hopes for easing to start any time soon. James Riley from our markets team has been looking at this issue and I spoke to him earlier in the week. I started by asking him what to take from the fact that stocks have been rising, even as rate cut expectations have been scaled back.

James Reilly

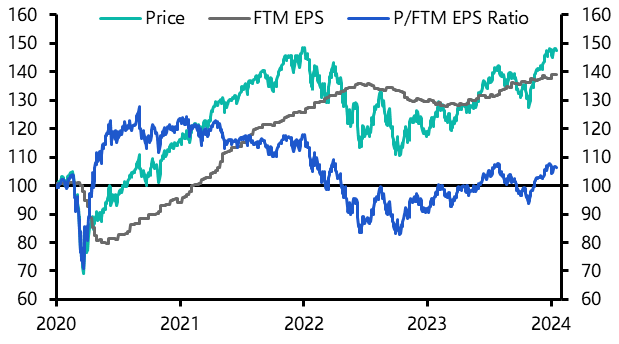

It says there's more to equity prices than simply what happens to risk -free rates. So yes, all else equal, higher treasury yields increases the discount rate applied to equity earnings and so reduces equity prices. But there is another component to this story and that's the equity risk premium. When I'm talking about the equity risk premium, I'm of course talking broadly about the excess return investors would get from invested equities rather than a risk-free asset such as US treasuries. Now that's not something that can be observed, but it can be estimated in various ways. And most of those estimates suggest it has narrowed a bit of late helping to offset that rise in treasury yields which you mentioned.

The obvious question after that is why has this equity risk premiere narrowed? The first explanation is that market conditions more broadly look pretty cheery, pretty benign. So credit spreads have narrowed a long way in most markets. Volatility across markets has come down since last year. That's all probably on the back of ongoing economic resilience and further inflation, which has helped to improve risk appetite. But the other reason, of course, is this ever growing hype around artificial intelligence and what it might mean for the economy in the future.

We saw in the dot -com bubble with internet and even the railway bubble, hype around transformative technology can also compress this equity risk premium. That's what we're seeing now and it's what we saw in the first half of last year too. That's the main reason why equities have shrugged off rising in treasury yields this year. The other explanation is on the earnings side of the equation. The likes of Nvidia in particular delivered strongly on that side and that's led to investors revising up their earnings expectations in many cases.

David Wilder

So given all that, when the Fed does come to cut rates - I think we're now forecasting that first move in June - is that going to supercharge this rally?

James Reilly

So a lot really depends on the backdrop in terms of economic activity, when those rate cuts come. When the Fed cuts against the backdrop of resilient economic activity, that does tend to feel pretty punchy gains in the US stock market. That's what we saw after the cuts around September 98 during the dot-com bubble, where that was followed by gains of about 35% in the 12 months after the first cut. But when the Fed cuts, against a recessionary backdrop that rarely proves enough to even stop the stock market falling outright. So if the Fed cuts in June or later this year were to come alongside a big slowdown in the US economy, it probably wouldn't supercharge the stock market. In fact, it might not prevent the stock market from even falling. But our view is that real GDP growth will come off the board a touch but remain fairly strong and that therefore when the Fed cuts rates in June as we forecast and continues cutting over the rest of this year, will help to supercharge this bubble. We think the S&P 500 will reach 5,500 this year and 6,500 next year.

David Wilder

So when the Fed does come to cut rates, let's look at this on a sectoral basis, what will that mean for the rate-sensitive sectors?

James Reilly

Yeah, so if the Fed cuts are accompanied by fall in treasury yields, which we would expect, that or our sequel tends to favour of course the so-called rate-sensitive sectors. The sectors where earnings are expected to come further out in time. So that includes the Magnificent 7 for the most part. They are companies expected to grow pretty rapidly over a number of years. The likes of Nvidia would historically be quite rate sensitive. So all else equal, rate cuts will be a boon for the Magnificent 7 and the related sectors. You know, another reason to expect those companies to continue to outperform. But actually we've seen, as I mentioned earlier, so far this year and last year, these companies haven't been particularly rate sensitive. They've been ploughing ahead regardless of what rates are doing. So that combination of fall in treasury yields, helping the Magnificent 7 and other rate sensitive sectors. But also more importantly, this continued growth in hype around AI are really the reasons we expect the Magnificent Seven and their sectors to continue to lead the market over the next coming years.

David Wilder

I can't let you go James without asking you about the election, the US election. We've just had Super Tuesday, Trump victorious in pretty much all of the primaries there. We'll have lots more to say about the election in the run-up to the November vote. But what can you say about this point, about what would happen to this stock market bubble if he did indeed win in November?

James Reilly

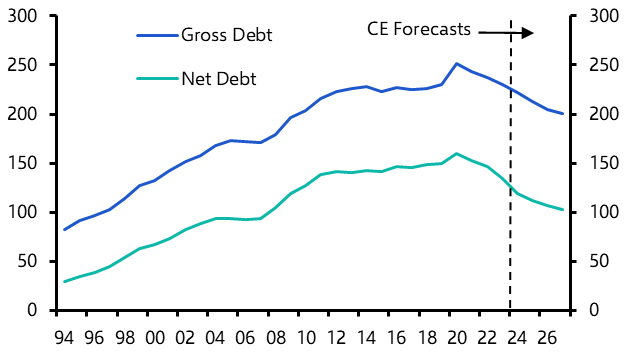

So when Trump won in 2016, his victory led to a big rally in the US stock market on the back of expectations for tax breaks for corporate America and a broader loosening of fiscal policy that led to cyclicals outperforming defensives and the stock market referring very strongly over late 2016 and 2017. The scope for a repeat this time looks pretty limited given the debt dynamics in the US. It's possible Trump could still go for more tax cuts and lose a fiscal policy and just ignore the meltdown in the treasury market, but we don't think he will do that. Instead, the main policy that looks set to kind of royal markets if Trump were to win is an escalation of the trade war with China and indeed universal tariffs on other economies to the tune of about 10%. We think that would be inflationary and push up treasury yields and it would also be damaging to both US and global growth. All things equal then that's putting downward pressure on valuations and equity earnings but we don't think it'd be enough of a hit to the economy to prevent a further compression of the equity risk premia and a further rise in stock prices. So we do think the bubble would continue to form even if Trump won albeit perhaps reaching lower heights than if Biden were to win. But that also does open the prospect of more risk to the bubble view in terms of factors which could burst this bubble. So one obvious example is if Europe were to respond to US tariffs with a big antitrust push against US big tech, that could be problematic because of course those companies are expected to lead this AI boom. And of course Trump himself and Republicans more broadly have themselves often spoken on the issue of antitrust. So if you're looking for factors which could eventually burst this bubble, this antitrust movement, if Trump were to win, is one to keep in mind.

David Wilder

James Riley there on Trump, the Fed and the stock market bubble. We're a lot closer to our end 2024 5,500 forecast than we were when we originally published it back in June. I'll post James's analysis and our guide to our S &P forecast on the podcast page. But that's it for this week. We'll be back next week with Liam Peach talking about the outlook for Russia and we'll have much more on the global macro picture, including a preview of the March meetings from the Fed, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England. Until next time, goodbye.