Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday February 2nd and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, a tsunami of commercial real estate loans coming due and what that means for banks. But first, Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist, joins me once again to give us the lowdown on the big macro market stories of the week gone and the week to come. Hi Neil, how's it going?

Neil Shearing

Hi there David, all good, and you?

David Wilder

Yeah, good. It has been a busy week and it's a busy week that ends on with a bang. We've got to start with that US jobs report. Non-farm payrolls just out, another massive expectations beat and big upwards revisions too. I guess it's the final nail in the coffin of March rate cut bets, but what are the other big takeaways besides that?

Neil Shearing

Yes, you're right. Actually, the employment report left our US economists wondering whether or not the Fed had had advanced sight of it. Given its strength, it would of course explain why Powell was so keen to push back on expectations of a March rate cut at the FOMC meeting in the past week. A lot of the focus will obviously fall on the large increase in payrolls in January, but I think those revisions that you mentioned are interesting and important too. Some potential for employment to be revised down. It was revised down a few months early in 2023, but actually the December number was revised up. So that perhaps suggests that the strong January number wasn't a fluke.

If you dig beneath the surface though, there's some parts of this report that are quite difficult to square. So for example, average working hours fell from 34.3 hours to 34.1. That's difficult to square with the fact that employment growth itself was so strong. Likewise, there was a really strong increase in average hourly earnings, 0.6 % month on month, which stands in stark contrast to the other evidence that we're getting that suggests that wage growth in the US is slowing. Our US economists take is that this may be related to the effect that an unseasonably cold January is having on the labour market. It was an unseasonably warm December. It might be the case that the cold weather in January explains hours reduced and perhaps jobs lost in lower wage occupation. So that would push up the average hourly earnings number and perhaps pull down the average weekly hours work number. So there's some parts of this report that don't quite knit together in a bit of a puzzle. But overall, no signs here certainly that the US labor market is about to crack.

David Wilder

Yeah, you mentioned that that Powell appearance after the FOMC decision and the reticence that he showed about cutting rates too soon, i.e. in March. He also spoke about wanting to see more “good data” before cutting rates, not “better data” he specified, but “good data”. On that basis, you mentioned those wage growth numbers. How would you categorise that do you think? Is this the kind of thing that Howell is concerned about?

Neil Shearing

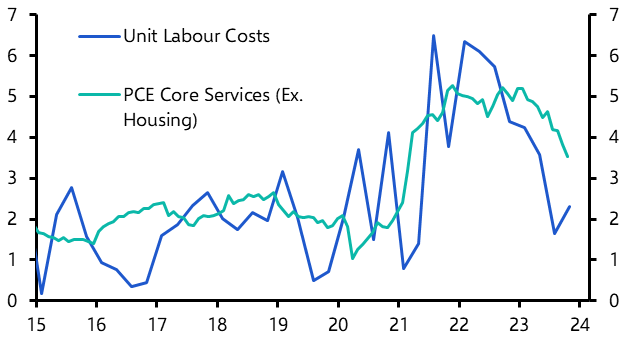

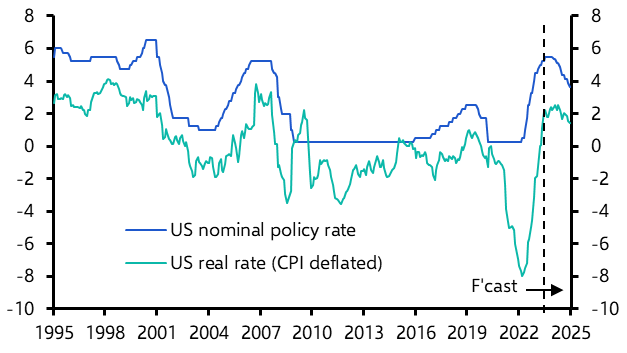

Well, the average hourly earnings numbers in that January jobs report are certainly going to raise a few eyebrows, but this isn't really the best measure of wage growth in the US economy. For that, if go back to Wednesday last week, we got the employment cost index report for the fourth quarter. The key difference is that the employment cost index adjusts amongst other things for the quality of jobs created, the types of jobs that are created. It's a much better indication of underlying wage growth. And on that front, there was good news for the Fed. Employment costs increased by 0.9 % quarter on quarter. That's a 3.7 % annualized pace. Earlier in the week, we got the JOLTS data. And if you look at the rates at which people are quitting jobs, so voluntary quits, they correlate very well with the employment cost index. That suggests that that 3.7 % annualized pace might slow to a three to three and a half percent range over the coming months. And that's perfectly consistent with a 2% inflation target when you've got productivity growth, rather than healthy rates in the US economy at the moment. So yes, the average hourly earnings number in the January jobs report will raise a few eyebrows, but actually I think the more reliable data is suggesting that wage pressures in the US economy are continuing to cool.

David Wilder

So after Powell explicitly ruled out a March rate cut at that press conference on Wednesday. Our US team were advising to look to May as the next opportunity for that first cut. Where does this January jobs report leave that probability?

Neil Shearing

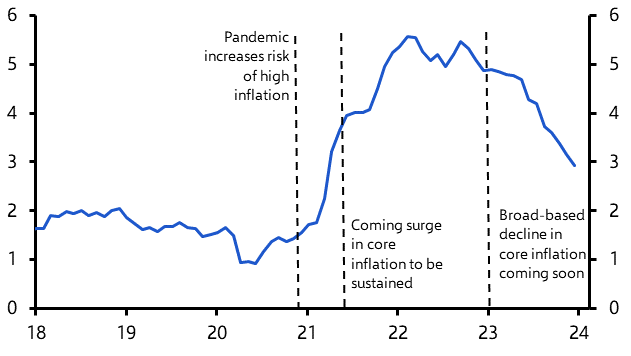

We can say definitively, I think now, can't we, that unless something drastic happens between now and March's FOMC, we're not going to get a March rate cut. The big question, as you say, is what happens in May? Our sense is that there's a lot of data that's due between now and then. When you look at it, I think most of that is still pointing to disinflation, slowing inflation continuing. I think it will support the case for rate cuts, particularly when we look, as I say, what's happening in the labor market, some signs that wage pressures are cooling. We know that there's likely to be further slowdowns in core inflation as shelter inflation cools. I think you put all that together. Yes, you're right, the markets have started to pull back a bit on May rate cuts, but I think there's still we talk about a 70 % chance of a rate cut coming in May. And our view, for what it's worth, is that May will be the time that the Fed starts to cut.

David Wilder

What about the Bank of England? We've had a decision from the Bank of England this past week, and the ECB a week before. It's clear that most policymakers in these banks don't want to rush into rate cuts, even if much of the headline inflation dates suggest that we're in the dying moments of this battle to get inflation under control. Obviously the US economy gives the Fed some breathing room to delay, to act cautiously on rates. But the euro-zone, UK economies, I mean, they've stalled at best, haven't they? Inflation falling fast there. Our UK team says the CPI in the UK could be under 1 % in September.

David Wilder

Is there a danger given all this that these banks were too slow to react to rising inflation two years ago? Now they're at the risk of being too slow to respond now that inflation is falling.

David Wilder

It's Friday February 2nd and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, a tsunami of commercial real estate loans coming due and what that means for banks. But first, Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist, joins me once again to give us the lowdown on the big macro market stories of the week gone and the week to come. Hi Neil, how's it going?

Neil Shearing

Hi there David, all good, and you?

David Wilder

Yeah, good. It has been a busy week and it's a busy week that ends on with a bang. We've got to start with that US jobs report. Non-farm payrolls just out, another massive expectations beat and big upwards revisions too. I guess it's the final nail in the coffin of March rate cut bets, but what are the other big takeaways besides that?

Neil Shearing

Yes, you're right. Actually, the employment report left our US economists wondering whether or not the Fed had had advanced sight of it. Given its strength, it would of course explain why Powell was so keen to push back on expectations of a March rate cut at the FOMC meeting in the past week. A lot of the focus will obviously fall on the large increase in payrolls in January, but I think those revisions that you mentioned are interesting and important too. Some potential for employment to be revised down. It was revised down a few months early in 2023, but actually the December number was revised up. So that perhaps suggests that the strong January number wasn't a fluke.

If you dig beneath the surface though, there's some parts of this report that are quite difficult to square. So for example, average working hours fell from 34.3 hours to 34.1. That's difficult to square with the fact that employment growth itself was so strong. Likewise, there was a really strong increase in average hourly earnings, 0.6 % month on month, which stands in stark contrast to the other evidence that we're getting that suggests that wage growth in the US is slowing. Our US economists take is that this may be related to the effect that an unseasonably cold January is having on the labour market. It was an unseasonably warm December. It might be the case that the cold weather in January explains hours reduced and perhaps jobs lost in lower wage occupation. So that would push up the average hourly earnings number and perhaps pull down the average weekly hours work number. So there's some parts of this report that don't quite knit together in a bit of a puzzle. But overall, no signs here certainly that the US labor market is about to crack.

David Wilder

Yeah, you mentioned that that Powell appearance after the FOMC decision and the reticence that he showed about cutting rates too soon, i.e. in March. He also spoke about wanting to see more “good data” before cutting rates, not “better data” he specified, but “good data”. On that basis, you mentioned those wage growth numbers. How would you categorise that do you think? Is this the kind of thing that Howell is concerned about?

Neil Shearing

Well, the average hourly earnings numbers in that January jobs report are certainly going to raise a few eyebrows, but this isn't really the best measure of wage growth in the US economy. For that, if go back to Wednesday last week, we got the employment cost index report for the fourth quarter. The key difference is that the employment cost index adjusts amongst other things for the quality of jobs created, the types of jobs that are created. It's a much better indication of underlying wage growth. And on that front, there was good news for the Fed. Employment costs increased by 0.9 % quarter on quarter. That's a 3.7 % annualized pace. Earlier in the week, we got the JOLTS data. And if you look at the rates at which people are quitting jobs, so voluntary quits, they correlate very well with the employment cost index. That suggests that that 3.7 % annualized pace might slow to a three to three and a half percent range over the coming months. And that's perfectly consistent with a 2% inflation target when you've got productivity growth, rather than healthy rates in the US economy at the moment. So yes, the average hourly earnings number in the January jobs report will raise a few eyebrows, but actually I think the more reliable data is suggesting that wage pressures in the US economy are continuing to cool.

David Wilder

So after Powell explicitly ruled out a March rate cut at that press conference on Wednesday. Our US team were advising to look to May as the next opportunity for that first cut. Where does this January jobs report leave that probability?

Neil Shearing

We can say definitively, I think now, can't we, that unless something drastic happens between now and March's FOMC, we're not going to get a March rate cut. The big question, as you say, is what happens in May? Our sense is that there's a lot of data that's due between now and then. When you look at it, I think most of that is still pointing to disinflation, slowing inflation continuing. I think it will support the case for rate cuts, particularly when we look, as I say, what's happening in the labor market, some signs that wage pressures are cooling. We know that there's likely to be further slowdowns in core inflation as shelter inflation cools. I think you put all that together. Yes, you're right, the markets have started to pull back a bit on May rate cuts, but I think there's still we talk about a 70 % chance of a rate cut coming in May. And our view, for what it's worth, is that May will be the time that the Fed starts to cut.

David Wilder

What about the Bank of England? We've had a decision from the Bank of England this past week, and the ECB a week before. It's clear that most policymakers in these banks don't want to rush into rate cuts, even if much of the headline inflation dates suggest that we're in the dying moments of this battle to get inflation under control. Obviously the US economy gives the Fed some breathing room to delay, to act cautiously on rates. But the euro-zone, UK economies, I mean, they've stalled at best, haven't they? Inflation falling fast there. Our UK team says the CPI in the UK could be under 1 % in September.

David Wilder

Is there a danger given all this that these banks were too slow to react to rising inflation two years ago? Now they're at the risk of being too slow to respond now that inflation is falling.

Neil Shearing

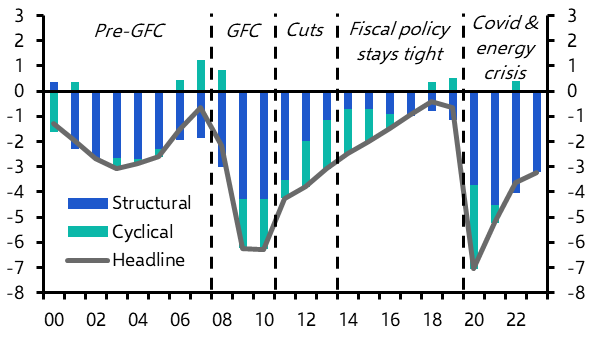

Well, to be fair to central bankers, and I don't think we always are fair to central bankers, but I think it's been a pretty difficult terrain to navigate over the past year or so. But I think there's something to what you say. I mean, in the case of the euro-zone, we had the GDP data over the past week suggesting that output flat essentially in the fourth quarter of last year. But if you look at the details, at least the details that we have that have been released so far, they're pretty grim. I mean, if you look at what's happening to domestic demand in places like France, it's cratering: consumer spending down, investment down. It's all looking pretty grim. So some signs of kind of real underlying economic weakness coming through in the eurozone economy and Germany, of course, in trouble too. How do you square that with what policymakers have told us over the past week or so? We've had more ECB officials coming out over the past several days try to put some colour on that decision to keep rates on hold and then set the summer as an expectation for rate cuts. I mean, I think it's pretty clear that no central banker wants to go down as this generation's Arthur Burns. So this is the head of the Fed in the 1970s that was widely, but probably unfairly blamed for letting the inflation genie out of the bottle in that decade. No one wants to be remembered as this generation's Arthur Burns. I think when you play that forward, what it means is that if it comes down to a choice between cutting rates too late and tolerating an economy that is weaker than would otherwise be the case, or cutting too early and potentially opening the door to another increase in inflation, they're much more likely to do the former than the latter. The problem, I think, as you suggest, is that if you look at the monthly inflation data in Europe and the UK, it paints a more reassuring picture, I think. So if you look at the month -on -month annualized rates of core inflation, they are, if not at 2% in the case of the UK, then they're getting there. And in the case of the eurozone, they're a bit below it on an annualized basis. And yes, we've seen some survey evidence that firms’ selling pricing expectations have picked up a bit in Europe over the past month or so. But really, I think there's signs now that the disinflation process is gathering pace. So difficult terrain for central banks to navigate but my sense is in Europe, they probably are being a bit unduly cautious. By the same token, this is what always happens in rate cutting cycles. The central banks are always pushed back against the idea that they're about to cut interest rates until such time that they do. So I don't think it's entirely unexpected, but by the same token, I don't think it means that we should necessarily rule out a rate cut in April in the case of the ECB and June in the case of the Bank of England.

David Wilder

You spoke on last week's podcast about the importance of data coming out of labour markets in helping decide the timing of rate cuts. Talk a bit more about what we're seeing in the labour markets in Europe and the UK. I know we've covered the US, so let's talk about those. They've also held up relatively well, haven't they? I mean, yes, we're seeing some signs of weakness, but nothing like what you'd expect at this stage of a monetary cycle. What do you think accounts for this resilience? And where do we go from here? Is it more gradual loosening that we've seen or is something more recessionary coming?

Neil Shearing

Well I think it's really important to view what's happening in labour markets in the context of the broader weird cycle that we've had such that it is a cycle since the pandemic. Related to that, the enormous dislocation that's happened to the labour supply in the euro-zone and in the UK over the past three to four years. The conventional way in which you would expect the labour market to respond to a weak economy is that demand goes down, hiring goes down, unemployment goes up. We've not seen that this time. However, we are seeing signs the labour market is cooling in other ways. So hiring intentions, fall in job vacancies are softening, but the quits rate we talked about in the case of the US, voluntary quits are falling in most countries too. And when you then map that to what's happening to wages, yes, the year on year growth rate of nominal wages is still uncomfortably high for central banks. But if you look at the month -on -month changes, seasonally adjust them, annualise them, they've fallen quite a long way. So what's happening here, I think, is the demand and supply coming into better balance across labour markets in Europe and for that matter, the US. And so we're getting that moderation in wage growth without there necessarily needing to be a big rise in unemployment. And obviously, this is at the heart of the so-called soft landing.

David Wilder

Let's go back to the US very quickly. You just mentioned the productivity growth numbers there. We're speaking a day after strong earnings reports from Meta and Amazon, both companies talking up gen AI as drivers of their business in their earnings calls. Is there a connection here between the productivity growth numbers we're seeing in the US and what these apparent leaders in driving the rollout of AI are saying? Is AI having this impact on productivity numbers?

Neil Shearing

I think there's a couple of points we can say with reasonable conviction and then there's lots of uncertainty. The things we can say with reasonable conviction is a.) productivity is a mystery to economists. It's quite difficult to know what drives it and what influences it from one quarter to another. The second is that it's pretty clear that AI and particularly the rollout of large language models and generative AI is having a meaningful impact on the earnings of some large tech companies. So it's clear that AI has boosted the top and bottom lines of the tech companies. I don't think it's yet clear that it's responsible for that improvement in US productivity growth that we've seen over the past couple of quarters. Now that's not to say that won't happen. In our Spotlight report last year. We made the case actually that we did think there would be a substantial boost to productivity growth, particularly in the US the role of AI, but that it would take time to happen. And so we've penciled in that rise coming in the latter half of this decade and into the 2030s. Could be that it's been rolled out a bit more quickly and that that rise in productivity is happening a bit sooner than we had anticipated. I think the other point we made in that report is that when you look back at the history of new technologies, the common thread is that markets tend to try to crystallise the perceived benefits of those technologies ahead of them actually happening in the real economy. That was certainly the case in the dot-com bubble of the 2000s. And our view is that something akin to that is playing out here. So I suspect that even if we don't start to see further improvements in US productivity growth as a result of AI, and that does come later in the decade, it's not going to stop the kind of AI hype and hysteria in parts of the equity market from continuing to build and this bubble continuing to inflate.

David Wilder

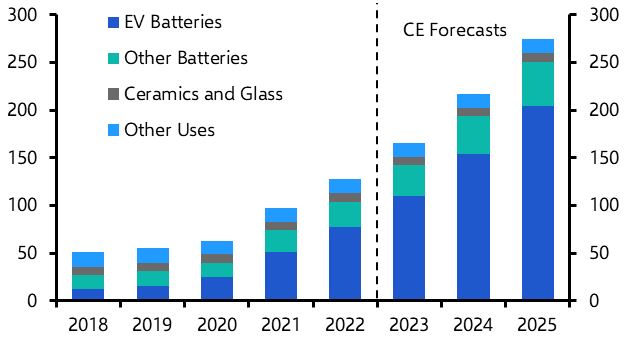

That was Neil Shearing on another Red Hot US jobs report, the latest from central banks, AI and productivity growth and much more besides. I'll post a new report on the US inflation outlook by our US team on the podcast page. Also details of the coming week's Drop-In – that's one of our short form online briefings, which is all about what's happening in the Red Sea and the risks to global inflation from that. That's on Wednesday 10am Eastern Time/ London 3 o'clock in the afternoon. On Thursday our EM team are holding an online briefing all about what's happening with EM central banks. Their monetary easing cycles started a while back. Question now is which bank will be next to cut and how far these cuts are going to go. And from inflation to deflation. Neil's weekly note out on Monday is all about China's policy dilemma and Chinese CPI and PPI for January are out on Thursday. Our China team is warning clients to brace for more evidence of deflation. Watch out for that coverage and their coverage of the new Chinese credit data, which is also due this coming week. Also look out for our recent analysis covering our new lithium price forecasts, Canadian wage inflation, euro-zone fiscal timing and the real stance of monetary policy. I'll post all of those reports on the podcast page too. Now, a shock announcement this past week from New York Community Bancorp has been a sharp reminder of the risk of exposure to commercial real estate as valuations plunge. We're just a month away from the one year anniversary of the collapse of SVB. That was a moment that crystallised fears that overvalued commercial real estate would be fuel for a new banking crisis. The crisis didn't happen, but real estate valuations have continued to tumble. Kiran Raichura from our US property team has been warning for months about mounting real estate distress. And I spoke to him earlier about the size and scope of the problems we're expecting in US CRE this year. Now this conversation took place just before New York Community's announcement. And it began with me asking Kieran why the issue of distressed real estate is coming back onto the agenda in 2024.

Kiran Raichura

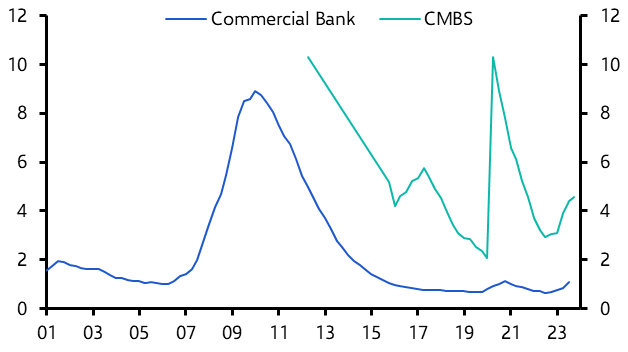

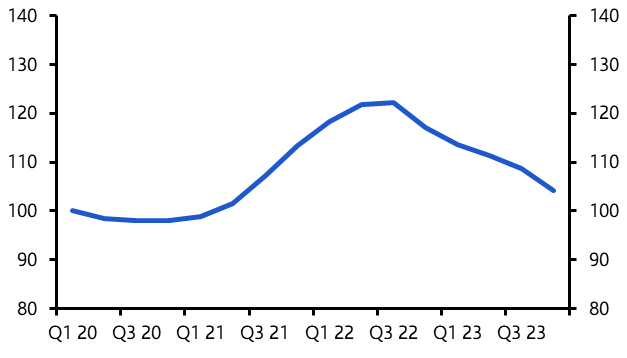

So it's back on the agenda because there are $1.2 trillion worth of loans due for refinance in 2024 and 2025. And those loans are maturing into both a higher interest rate environment and property value falls, which are already just close to 15%. And we think will exceed 20 % ultimately, making it the worst downturn since the Global Financial Crisis. If you think about last year, there were also concerns then about distress coming through, but ultimately it was a pretty quiet period in the end because of a couple of factors. Firstly, some banks sought to get ahead of the problems with discounted loan sales to try and de -leverage some of that risk. And secondly, there seems to be evidence that there are a large number of loan extensions. So bank loans usually allow for one year, sometimes two years of extensions, which would then mitigate that risk in the short term. But we are starting to see signs of impaired loans coming through. So some borrowers handed keys back for their worst hit assets. And there were some examples last year in the West Coast office markets and New York City. And then following those few, banks then generally sought to work with borrowers to avoid ending up with loads of assets on their books. And we've also seen CMBS delinquency rates rise. So that records loans that are 30 days or more in arrears. And for CMBS, those data can't be papered over in the short term like bank loans can through those extensions. And so for CMBS delinquency, that figure has risen from 3 % to 4.5 % last year. And so essentially what's back on the agenda is that there's already some refinancing due in 2024 and 2025, as well as those loans that were extended last year for a year or so. So at this point, those loans have been extended, further extensions are likely to be an option. So those investors will need to either find refinancing or sell those assets.

David Wilder

We're forecasting the Fed to start cutting rates from their May meeting onwards and to cut over the whole of 2024 by 150 basis points. It's an environment of falling short-term rates that these loans are maturing into. Won't that mitigate the impact of at least some of this debt maturing?

Kiran Raichura

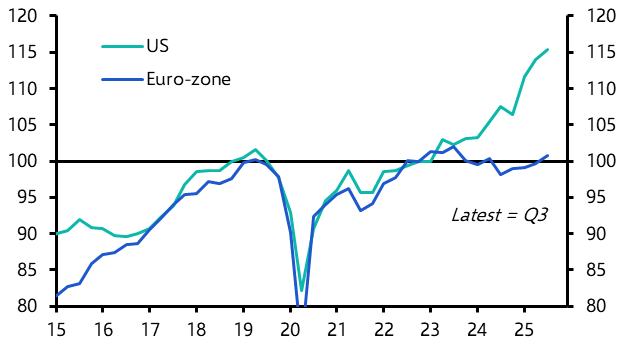

Yes, there will be a partial offset. So while the short rates are likely to fall quite substantially, we've pretty much seen all of the fall that we're expecting in the 10-year rate. So that again still implies a lower rate of interest than we were looking at at the end of last year. It's still going to be much higher than the rate at which those loans were initially agreed at. And so in terms of where those risks fall, you can think about this in terms of the two major banking covenants online. So the loan to value covenant and the interest coverage ratio. And so on the latter, that's where the interest rate is most relevant. But the issue is that, as I said before, long rates are much higher than they were in 2021 when a lot of those loans were agreed. And so borrowers who took out fixed rate loans in that period, they'll face a doubling of interest costs in some cases. And so that will put some interest coverage ratios below one, meaning that banks will demand cash to reduce the size of a loan and reduce future interest payments. And then go back to the other one that falls in values that I referred to earlier. So far we're down 15% and those falls will put many loads of value covenants under threat, meaning that again, there'll be capital needed to either refinance those loans or investors will be looking to sell those assets or get capital injected in to enable them to continue as they are.

David Wilder

I mean, there's pretty wide variance in your forecast for valuations across sectors and across regions. Looking at the US in total, where do you think the risks are greatest? Also, where are we going to see outperformance?

Kiran Raichura

For us, the biggest risk comes in the office sector. So their values are down nearly 30 % already. And in that sector, it's not just an adjustment in pricing to a higher interest rate or the cyclical slowdown we've seen over the last year or so, but it's much more about this structural change and adjustment to remote and hybrid work. And so over time, we think net operating incomes, which is the rent minus cost of operating the assets, so management costs, insurance, et cetera. We think those will continue to soften as rental values fall and occupancy falls. So office incomes will reduce for landlords. And because we think it's a structural change, there won't be a viable option for that sector for lenders to simply extend loans and hope for a recovery. So the so-called ‘survive to 2025’, we don't think that really applies for the office sector. And so there we do expect to see a substantial amount of assets being forced to be sold or ending back on lenders books. So that's definitely the downside or the weakest sector. We're also reasonably concerned about some risks in the multifamily sector. There, that's much more of a focus on the interest coverage angle I described previously. So you had loans being agreed at around 3% as an average interest rate in 2020 to 21. And that's pretty much doubled to 6% or maybe more in recent times. So where those loans come off, those fixed rates need to be refinanced. There's a risk there. And at the same time, you know, net operating income growth hasn't been strong enough to offset that. And that's partly because you've had increases in various costs, but in particular, insurance costs in some coastal markets. But I think for that sector, we think it's much more of a specific issue for those loans taken out in those two years or so, 2020 to 2021, and particularly in those coastal markets where they've had a big increase in insurance costs. And in the South, where there's been this big extent of overbuilding that we think will start to come, or has started to come through last year. And again, in that sector it’s is a bit different to offices because it's much more of a short term blip really in terms of the income stream. So we think their banks and investors may be able to pretend for long enough to get them through the short term. And then I guess as far as upside goes, retailers is a sector that we think will see the smallest falls. In fact, we think that the capital value falls are almost over for that sector. But actually there, then there's probably more of an opportunity on the equity side rather than on the debt side.

David Wilder

Taking it all together, this all sounds quite scary. We're just over a month away from the one year anniversary of the SVB collapse and that crystallized fears about exposure to commercial real estate. A US team at the time was warning that there were scenarios where this could create this adverse feedback loop between small banks and the real estate sector, carry echoes of the savings and loan crisis in the early 80s. Talk about these maturities that you're talking about. What does that mean for US banks, is something going to break here, do you think?

Kiran Raichura

Okay, well I think that's fairly unlikely. In the end, I think systemic risks here are likely to be fairly low for three main reasons. Firstly, while we expect all property values falls to reach around 20 % this year, we think that a forward -looking approach by lenders will mean that industrial and multifamily assets for those, they'll look through the short -term pain where possible, as I just mentioned in terms of multifamily sector, because those sectors have good long-term stories. So banks are likely to work with borrowers and if anything, there are big investors out there who are looking to take advantage of opportunities where maybe availability or cost of capital is an issue, but the assets themselves are fundamentally solid. On the other hand, we think the major source of pain will be in offices where we've argued that values won't recover their pre -pandemic levels at least until the 2040s. But in that sector, the positive is that the bigger loans tend to be held by bigger banks. And that brings me on to my second factor, which is that the big banks look to be well capitalised and with lower shares of CRE loans on their books. Of course, there could be risks amongst the smaller banks where they have much higher shares of CRE loans and in particular exposure to maybe poorer offices and poorer-located multifamily assets. And there are estimates out there in the market that there will be large numbers of small bank failures. But fundamentally underpinning all of this and the kind of third factor is that we think the Fed will step in quickly if these risks resurface at a systemic level, which is essentially what we saw last year. And that's presumably something that's been done in part with Lehman and the financial crisis still relatively fresh in their minds.

David Wilder

Kiran Raichura there on real estate distress and banking sector vulnerability. He's got another note on this developing issue out early in the coming week, focused on the multifamily sector. I'll post it on the podcast page once it's out. But you can also find it on the US commercial proxy page of our website, capitaleconomics .com. And if you're not directly involved in US CRE, but you need to understand the risks around it, then CE Advance access will give you all of our coverage to that as well as tools to engage directly with Kieran and the team. It also opens up a world of interactive and proprietary data and much more besides. Get in touch if you'd like to learn more about our premium platform CE Advance. But that's it for this week. Until next time, goodbye.

Well, to be fair to central bankers, and I don't think we always are fair to central bankers, but I think it's been a pretty difficult terrain to navigate over the past year or so. But I think there's something to what you say. I mean, in the case of the euro-zone, we had the GDP data over the past week suggesting that output flat essentially in the fourth quarter of last year. But if you look at the details, at least the details that we have that have been released so far, they're pretty grim. I mean, if you look at what's happening to domestic demand in places like France, it's cratering: consumer spending down, investment down. It's all looking pretty grim. So some signs of kind of real underlying economic weakness coming through in the eurozone economy and Germany, of course, in trouble too. How do you square that with what policymakers have told us over the past week or so? We've had more ECB officials coming out over the past several days try to put some colour on that decision to keep rates on hold and then set the summer as an expectation for rate cuts. I mean, I think it's pretty clear that no central banker wants to go down as this generation's Arthur Burns. So this is the head of the Fed in the 1970s that was widely, but probably unfairly blamed for letting the inflation genie out of the bottle in that decade. No one wants to be remembered as this generation's Arthur Burns. I think when you play that forward, what it means is that if it comes down to a choice between cutting rates too late and tolerating an economy that is weaker than would otherwise be the case, or cutting too early and potentially opening the door to another increase in inflation, they're much more likely to do the former than the latter. The problem, I think, as you suggest, is that if you look at the monthly inflation data in Europe and the UK, it paints a more reassuring picture, I think. So if you look at the month -on -month annualized rates of core inflation, they are, if not at 2% in the case of the UK, then they're getting there. And in the case of the eurozone, they're a bit below it on an annualized basis. And yes, we've seen some survey evidence that firms’ selling pricing expectations have picked up a bit in Europe over the past month or so. But really, I think there's signs now that the disinflation process is gathering pace. So difficult terrain for central banks to navigate but my sense is in Europe, they probably are being a bit unduly cautious. By the same token, this is what always happens in rate cutting cycles. The central banks are always pushed back against the idea that they're about to cut interest rates until such time that they do. So I don't think it's entirely unexpected, but by the same token, I don't think it means that we should necessarily rule out a rate cut in April in the case of the ECB and June in the case of the Bank of England.

David Wilder

You spoke on last week's podcast about the importance of data coming out of labour markets in helping decide the timing of rate cuts. Talk a bit more about what we're seeing in the labour markets in Europe and the UK. I know we've covered the US, so let's talk about those. They've also held up relatively well, haven't they? I mean, yes, we're seeing some signs of weakness, but nothing like what you'd expect at this stage of a monetary cycle. What do you think accounts for this resilience? And where do we go from here? Is it more gradual loosening that we've seen or is something more recessionary coming?

Neil Shearing

Well I think it's really important to view what's happening in labour markets in the context of the broader weird cycle that we've had such that it is a cycle since the pandemic. Related to that, the enormous dislocation that's happened to the labour supply in the euro-zone and in the UK over the past three to four years. The conventional way in which you would expect the labour market to respond to a weak economy is that demand goes down, hiring goes down, unemployment goes up. We've not seen that this time. However, we are seeing signs the labour market is cooling in other ways. So hiring intentions, fall in job vacancies are softening, but the quits rate we talked about in the case of the US, voluntary quits are falling in most countries too. And when you then map that to what's happening to wages, yes, the year on year growth rate of nominal wages is still uncomfortably high for central banks. But if you look at the month -on -month changes, seasonally adjust them, annualise them, they've fallen quite a long way. So what's happening here, I think, is the demand and supply coming into better balance across labour markets in Europe and for that matter, the US. And so we're getting that moderation in wage growth without there necessarily needing to be a big rise in unemployment. And obviously, this is at the heart of the so-called soft landing.

David Wilder

Let's go back to the US very quickly. You just mentioned the productivity growth numbers there. We're speaking a day after strong earnings reports from Meta and Amazon, both companies talking up gen AI as drivers of their business in their earnings calls. Is there a connection here between the productivity growth numbers we're seeing in the US and what these apparent leaders in driving the rollout of AI are saying? Is AI having this impact on productivity numbers?

Neil Shearing

I think there's a couple of points we can say with reasonable conviction and then there's lots of uncertainty. The things we can say with reasonable conviction is a.) productivity is a mystery to economists. It's quite difficult to know what drives it and what influences it from one quarter to another. The second is that it's pretty clear that AI and particularly the rollout of large language models and generative AI is having a meaningful impact on the earnings of some large tech companies. So it's clear that AI has boosted the top and bottom lines of the tech companies. I don't think it's yet clear that it's responsible for that improvement in US productivity growth that we've seen over the past couple of quarters. Now that's not to say that won't happen. In our Spotlight report last year. We made the case actually that we did think there would be a substantial boost to productivity growth, particularly in the US the role of AI, but that it would take time to happen. And so we've penciled in that rise coming in the latter half of this decade and into the 2030s. Could be that it's been rolled out a bit more quickly and that that rise in productivity is happening a bit sooner than we had anticipated. I think the other point we made in that report is that when you look back at the history of new technologies, the common thread is that markets tend to try to crystallise the perceived benefits of those technologies ahead of them actually happening in the real economy. That was certainly the case in the dot-com bubble of the 2000s. And our view is that something akin to that is playing out here. So I suspect that even if we don't start to see further improvements in US productivity growth as a result of AI, and that does come later in the decade, it's not going to stop the kind of AI hype and hysteria in parts of the equity market from continuing to build and this bubble continuing to inflate.

David Wilder

That was Neil Shearing on another Red Hot US jobs report, the latest from central banks, AI and productivity growth and much more besides. I'll post a new report on the US inflation outlook by our US team on the podcast page. Also details of the coming week's Drop-In – that's one of our short form online briefings, which is all about what's happening in the Red Sea and the risks to global inflation from that. That's on Wednesday 10am Eastern Time/ London 3 o'clock in the afternoon. On Thursday our EM team are holding an online briefing all about what's happening with EM central banks. Their monetary easing cycles started a while back. Question now is which bank will be next to cut and how far these cuts are going to go. And from inflation to deflation. Neil's weekly note out on Monday is all about China's policy dilemma and Chinese CPI and PPI for January are out on Thursday. Our China team is warning clients to brace for more evidence of deflation. Watch out for that coverage and their coverage of the new Chinese credit data, which is also due this coming week. Also look out for our recent analysis covering our new lithium price forecasts, Canadian wage inflation, euro-zone fiscal timing and the real stance of monetary policy. I'll post all of those reports on the podcast page too. Now, a shock announcement this past week from New York Community Bancorp has been a sharp reminder of the risk of exposure to commercial real estate as valuations plunge. We're just a month away from the one year anniversary of the collapse of SVB. That was a moment that crystallised fears that overvalued commercial real estate would be fuel for a new banking crisis. The crisis didn't happen, but real estate valuations have continued to tumble. Kiran Raichura from our US property team has been warning for months about mounting real estate distress. And I spoke to him earlier about the size and scope of the problems we're expecting in US CRE this year. Now this conversation took place just before New York Community's announcement. And it began with me asking Kieran why the issue of distressed real estate is coming back onto the agenda in 2024.

Kiran Raichura

So it's back on the agenda because there are $1.2 trillion worth of loans due for refinance in 2024 and 2025. And those loans are maturing into both a higher interest rate environment and property value falls, which are already just close to 15%. And we think will exceed 20 % ultimately, making it the worst downturn since the Global Financial Crisis. If you think about last year, there were also concerns then about distress coming through, but ultimately it was a pretty quiet period in the end because of a couple of factors. Firstly, some banks sought to get ahead of the problems with discounted loan sales to try and de -leverage some of that risk. And secondly, there seems to be evidence that there are a large number of loan extensions. So bank loans usually allow for one year, sometimes two years of extensions, which would then mitigate that risk in the short term. But we are starting to see signs of impaired loans coming through. So some borrowers handed keys back for their worst hit assets. And there were some examples last year in the West Coast office markets and New York City. And then following those few, banks then generally sought to work with borrowers to avoid ending up with loads of assets on their books. And we've also seen CMBS delinquency rates rise. So that records loans that are 30 days or more in arrears. And for CMBS, those data can't be papered over in the short term like bank loans can through those extensions. And so for CMBS delinquency, that figure has risen from 3 % to 4.5 % last year. And so essentially what's back on the agenda is that there's already some refinancing due in 2024 and 2025, as well as those loans that were extended last year for a year or so. So at this point, those loans have been extended, further extensions are likely to be an option. So those investors will need to either find refinancing or sell those assets.

David Wilder

We're forecasting the Fed to start cutting rates from their May meeting onwards and to cut over the whole of 2024 by 150 basis points. It's an environment of falling short-term rates that these loans are maturing into. Won't that mitigate the impact of at least some of this debt maturing?

Kiran Raichura

Yes, there will be a partial offset. So while the short rates are likely to fall quite substantially, we've pretty much seen all of the fall that we're expecting in the 10-year rate. So that again still implies a lower rate of interest than we were looking at at the end of last year. It's still going to be much higher than the rate at which those loans were initially agreed at. And so in terms of where those risks fall, you can think about this in terms of the two major banking covenants online. So the loan to value covenant and the interest coverage ratio. And so on the latter, that's where the interest rate is most relevant. But the issue is that, as I said before, long rates are much higher than they were in 2021 when a lot of those loans were agreed. And so borrowers who took out fixed rate loans in that period, they'll face a doubling of interest costs in some cases. And so that will put some interest coverage ratios below one, meaning that banks will demand cash to reduce the size of a loan and reduce future interest payments. And then go back to the other one that falls in values that I referred to earlier. So far we're down 15% and those falls will put many loads of value covenants under threat, meaning that again, there'll be capital needed to either refinance those loans or investors will be looking to sell those assets or get capital injected in to enable them to continue as they are.

David Wilder

I mean, there's pretty wide variance in your forecast for valuations across sectors and across regions. Looking at the US in total, where do you think the risks are greatest? Also, where are we going to see outperformance?

Kiran Raichura

For us, the biggest risk comes in the office sector. So their values are down nearly 30 % already. And in that sector, it's not just an adjustment in pricing to a higher interest rate or the cyclical slowdown we've seen over the last year or so, but it's much more about this structural change and adjustment to remote and hybrid work. And so over time, we think net operating incomes, which is the rent minus cost of operating the assets, so management costs, insurance, et cetera. We think those will continue to soften as rental values fall and occupancy falls. So office incomes will reduce for landlords. And because we think it's a structural change, there won't be a viable option for that sector for lenders to simply extend loans and hope for a recovery. So the so-called ‘survive to 2025’, we don't think that really applies for the office sector. And so there we do expect to see a substantial amount of assets being forced to be sold or ending back on lenders books. So that's definitely the downside or the weakest sector. We're also reasonably concerned about some risks in the multifamily sector. There, that's much more of a focus on the interest coverage angle I described previously. So you had loans being agreed at around 3% as an average interest rate in 2020 to 21. And that's pretty much doubled to 6% or maybe more in recent times. So where those loans come off, those fixed rates need to be refinanced. There's a risk there. And at the same time, you know, net operating income growth hasn't been strong enough to offset that. And that's partly because you've had increases in various costs, but in particular, insurance costs in some coastal markets. But I think for that sector, we think it's much more of a specific issue for those loans taken out in those two years or so, 2020 to 2021, and particularly in those coastal markets where they've had a big increase in insurance costs. And in the South, where there's been this big extent of overbuilding that we think will start to come, or has started to come through last year. And again, in that sector it’s is a bit different to offices because it's much more of a short term blip really in terms of the income stream. So we think their banks and investors may be able to pretend for long enough to get them through the short term. And then I guess as far as upside goes, retailers is a sector that we think will see the smallest falls. In fact, we think that the capital value falls are almost over for that sector. But actually there, then there's probably more of an opportunity on the equity side rather than on the debt side.

David Wilder

Taking it all together, this all sounds quite scary. We're just over a month away from the one year anniversary of the SVB collapse and that crystallized fears about exposure to commercial real estate. A US team at the time was warning that there were scenarios where this could create this adverse feedback loop between small banks and the real estate sector, carry echoes of the savings and loan crisis in the early 80s. Talk about these maturities that you're talking about. What does that mean for US banks, is something going to break here, do you think?

Kiran Raichura

Okay, well I think that's fairly unlikely. In the end, I think systemic risks here are likely to be fairly low for three main reasons. Firstly, while we expect all property values falls to reach around 20 % this year, we think that a forward -looking approach by lenders will mean that industrial and multifamily assets for those, they'll look through the short -term pain where possible, as I just mentioned in terms of multifamily sector, because those sectors have good long-term stories. So banks are likely to work with borrowers and if anything, there are big investors out there who are looking to take advantage of opportunities where maybe availability or cost of capital is an issue, but the assets themselves are fundamentally solid. On the other hand, we think the major source of pain will be in offices where we've argued that values won't recover their pre -pandemic levels at least until the 2040s. But in that sector, the positive is that the bigger loans tend to be held by bigger banks. And that brings me on to my second factor, which is that the big banks look to be well capitalised and with lower shares of CRE loans on their books. Of course, there could be risks amongst the smaller banks where they have much higher shares of CRE loans and in particular exposure to maybe poorer offices and poorer-located multifamily assets. And there are estimates out there in the market that there will be large numbers of small bank failures. But fundamentally underpinning all of this and the kind of third factor is that we think the Fed will step in quickly if these risks resurface at a systemic level, which is essentially what we saw last year. And that's presumably something that's been done in part with Lehman and the financial crisis still relatively fresh in their minds.

David Wilder

Kiran Raichura there on real estate distress and banking sector vulnerability. He's got another note on this developing issue out early in the coming week, focused on the multifamily sector. I'll post it on the podcast page once it's out. But you can also find it on the US commercial proxy page of our website, capitaleconomics .com. And if you're not directly involved in US CRE, but you need to understand the risks around it, then CE Advance access will give you all of our coverage to that as well as tools to engage directly with Kieran and the team. It also opens up a world of interactive and proprietary data and much more besides. Get in touch if you'd like to learn more about our premium platform CE Advance. But that's it for this week. Until next time, goodbye.