Global bond markets have clawed back some of the wrenching losses of recent weeks, but yields remain far above levels seen over much of the post-global financial crisis period. This shift upwards reflects a painful adjustment from the zero interest-rate policy (ZIRP) that central bankers came to rely on after that crisis.

But questions linger about whether the era of ultra-low rates is really over and, if ZIRP really is dead, how high will rates finally settle once this post-pandemic inflationary burst subsides?

It’s a debate that often invites accusations of needless wonkery. But this isn’t just a distraction of economists sitting in ivory towers. The level at which rates will ultimately settle will have direct implications across the full spectrum of asset prices and uncertainty about that level has been a key factor behind the recent sell-off in the bond market. It is an issue that we will tackle in a major report to be published tomorrow.

At its core sits the question of what has happened to equilibrium real interest rates, or R*. This is the (real) interest rate that balances planned investment and desired saving in an economy at full employment.

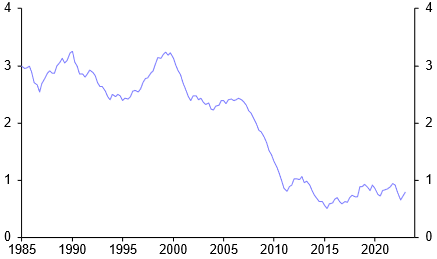

The three decades prior to the pandemic were characterised by a marked decline in R*. According to estimates by the New York Fed, equilibrium real interest rates in advanced economies averaged around 3% in the 1990s. But several structural forces, including a slowdown in potential economic growth and a large cohort of workers saving for retirement, started to bear down on real rates throughout the 2000s. And the process of balance sheet repair that followed the global financial crisis then put further downward pressure on R* in the 2010s, leaving it at just over 0.5% on the eve of the pandemic. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: R* in Advanced Economies |

|

|

|

Sources: Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2017). OECD |

What’s more, since the past three decades also saw a steep fall in inflation, equilibrium nominal interest fell by even more than real rates. As nominal rates hit the zero lower bound, central banks were forced to turn to quantitative easing in order to provide additional monetary support in the wake of the GFC.

The challenge for central banks today is radically different from the 2010s. Rather than trying to provide additional support for demand against the backdrop of persistent deflationary risks and the threat of a liquidity trap, they are facing excess demand, strong labour markets and resurgent inflation. Calibrating the policy response requires understanding whether and by how much equilibrium interest rates have moved. Our report makes two important points. The first is that while R* is a useful analytical concept, estimating it is more of an art than a science. The second is that, measurement challenges notwithstanding, there are good reasons to think it has risen over the past few years.

For one thing, many of the forces that suppressed R* in the 2010s have faded. Most obviously, the process of deleveraging and balance sheet repair that followed the GFC has run its course. As a result, we think that R* in the US is now around 1.0% or so – meaning that if inflation falls back to 2-3% over the next year, as we expect, the real stance of monetary policy will become significantly restrictive at the current level of interest rates. The same is true of the UK and euro-zone.

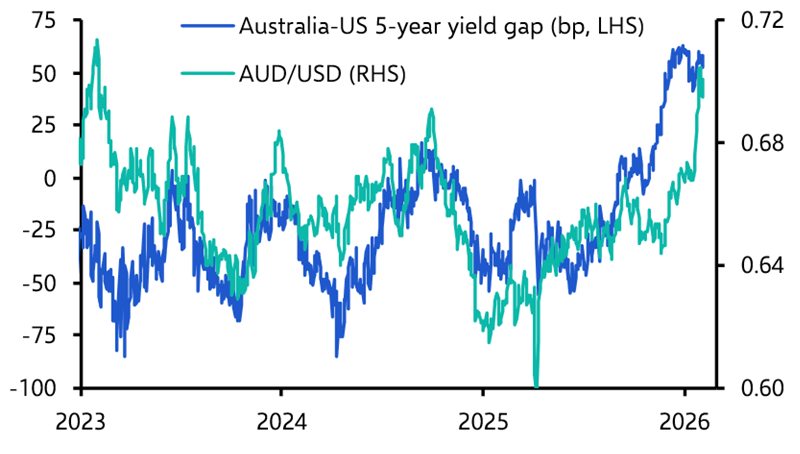

More importantly, we think that R* will rise further over the coming years. This is partly because potential GDP growth will be boosted by a pick-up in productivity growth as developments in artificial intelligence (AI) bear fruit. On top of this, several factors will also tip the balance of desired savings and investment in favour of higher interest rates. Demographic trends will reduce desired savings as more people retire, and opportunities in AI and the green transition will offer incentives to invest. What’s more, the pandemic seems to have triggered a permanent rise in government borrowing which will absorb more private savings. All of this will cause R* to increase over time. We think it will rise to 1.5-2.0% in the US by the end of this decade and to 1.0-1.5% in the UK and euro-zone. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Real Equilibrium Interest Rates (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Capital Economics, OECD, Holston, Laubach, and Williams |

As for inflation, we think that the days of persistent undershoots relative to central bank targets are behind us. Some of the post-pandemic increase in workers’ bargaining power will be sustained and with US-China fracturing and climate change adding to the pressure, overshoots of 2% targets will become more common over the coming decade.

All of this adds up to a significant increase in equilibrium real and nominal interest rates compared to the rock bottom levels that prevailed during the 2010s. That’s not to say that the sell-off in global bonds has not gone too far — as I argued last week, there are good reasons to think yields will begin to edge down over the next three to six months. But they will do so within the context of a structurally higher environment for interest rates.

As tomorrow’s report will argue, investors everywhere need to plan for a period in which interest rates are significantly higher than they have become accustomed to. And, as we will make clear, that has big implications for bond yields and asset valuations everywhere.

‘R* and the end of the ultra-low rates era’ will be made available to CE Advance clients and to subscribers to our Global Economics, Global Markets and Long Run coverage on Tuesday, 17th October. Get in touch sales@capitaleconomics.com if you’d like to learn more about our analysis of R*.

In case you missed it:

Our coverage of the macro and market implications of the Israel-Hamas conflict spans risks to oil and gas markets, the impact on regional dynamics and financial market effects. The latest episode of our weekly podcast includes more discussion on the outlook.

Italy may not face the immediate threat of a big sell-off in its debt, but recent signals from the government – against the backdrop of rising yields globally – point to heightened long-term risk, says Chief Europe Economist Andrew Kenningham.

China Economics head Julian Evans-Pritchard shows why a looming update of US export controls will make it even harder for Chinese firms to keep up in the global AI race.

Exit polls suggest that Poland’s opposition party are on course for a majority in Sunday’s parliamentary elections. Liam Peach and Nicholas Farr showed why the outcome of the vote could be so decisive for the direction of Poland’s economy in the coming years.