Tariffs are coming. That seems to be one of the key takeaways from an extraordinary week which began with relief that the new president’s inaugural address skipped talk of tariffs, but was followed by a stream of threats from Donald Trump to start raising duties on leading trade partners – and ended with reports suggesting tariffs could be imposed on Mexico and Canada as soon as this weekend.

All of this has poured some cold water on the idea, still lurking in some parts of the market, that the threat to impose tariffs was bluster. It now seems likely that higher tariffs are in the pipeline and, as we have embedded in our central forecasts, that they could be imposed relatively soon. However, key questions remain. At what level and on what goods will tariffs be levied? Which countries beyond Mexico and Canada will be affected? And, just as important, will tariffs be used primarily as a tool to extract concessions from trading partners or as a means to raise permanent revenues for the US government? Weeks of additional speculation lie ahead but, until these threats become policy, nobody really knows.

There’s more to trade than tariffs

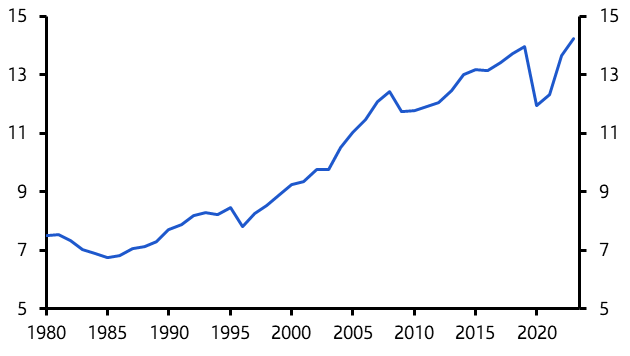

All of this has created unease in markets and led to talk of a new trade war. Some perspective is nonetheless important. Tariffs may dominate headlines, but there is far more to the global trade story than duties on goods. Services, which aren’t subject to tariffs, have surged as a percentage of total global trade over the past three decades. And even where tariffs are imposed, they are not done so in isolation – economies and markets are fluid systems that can adapt to higher-tariff environments. That includes exchange rates adjusting to cushion the effect of tariffs, and new technologies that develop to make trade profitable irrespective of levies. Finally, the response of other countries is critically important. The world could experience a 1930s-style collapse in trade if US tariffs trigger a similarly aggressive response from its trade partners. But if other countries respond to tariffs in a measured way – and maintain relatively free trade with each other – then the effect on global trade volumes will be more modest. The experience under previous administrations, including the first Trump presidency, offers some reason for hope.

|

Chart 1: Global Services Trade (% of Global GDP) |

|

|

|

Source: World Bank, Capital Economics |

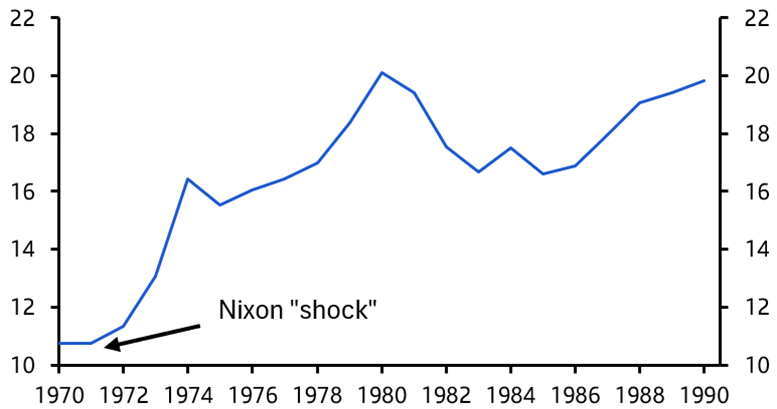

Economic historian Doug Irwin drew parallels between Trump and Richard Nixon’s presidency on a recent Financial Times podcast. Not only did Nixon impose a 10% universal tariff on all imports when the US came off gold in 1971 (which, incidentally, in practice covered only half of imports to the US) but his administration’s rhetoric was decidedly Trumpian. This included Treasury Secretary John Connally’s declaration that “all foreigners are out to screw us. Our job is to screw them first”. Despite this undiplomatic tone, both US and global trade increased in the 1970s. (See Chart 2.) Likewise, a period of so-called “trade restraint” under Ronald Reagan did not have a lasting impact on US trade – at the end of Reagan’s second term in 1988, US trade as a share of GDP was a little higher than when he entered office in 1981. (Again, see Chart 2.) This is to say that tariffs and other policies are important, but they are only one factor shaping global trade flows.

|

Chart 2: US Trade (Exports & Imports as a % of GDP) |

|

|

| Sources: World Bank, Capital Economics |

Back to the future?

What lessons can we draw for today? Trump’s motives are unclear. His rhetoric is isolationist and it is clear that he (incorrectly) views America’s trade balance as a barometer of national wealth and prosperity. Others in his administration are said to share similar views, although it may prove significant that senior figures in his new cabinet have a background on Wall Street. Irwin suggested that the possibility of an adverse reaction in the stock market could act as a brake on some of Trump’s more radical trade proposals. This is possible, but far from guaranteed.

Through this fog of uncertainty there are three things we can be reasonably sure about. First, while tariffs aren’t everything, a 25% levy would deal a devastating blow to both Mexico and Canada’s economies. Both would likely fall into recession if the tariffs were kept in place long enough. They would also create chaos in North American supply chains. The impact on the US would also be significant.

The second thing that seems likely is that other countries will respond to US tariffs in a way that is designed to minimise the threat of escalation. Media reports suggest that Canada is considering placing tariffs on imports of orange juice and bourbon. These have political resonance – Florida is a major producer of orange juice and Kentucky a major producer of bourbon. Both are important parts of Trump’s base. But they account for a small share of bilateral trade. This would mimic the response to tariffs during the first Trump administration, where retaliation was calibrated in a way that maximised the political impact while containing the economic damage. This would reduce the risk of a slide into 1930s-style protectionism on a global level.

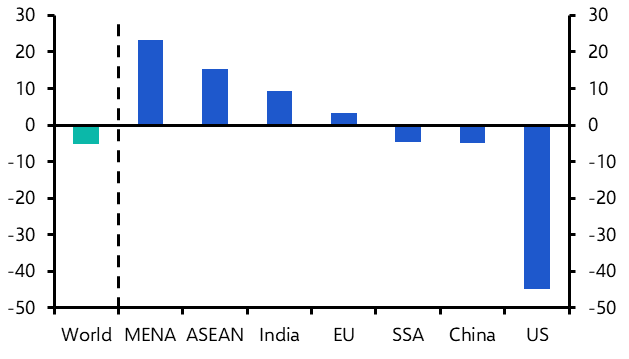

China is still the main target

Finally, we can be reasonably sure that, while Canada and Mexico have found themselves under immediate pressure, containing China will be a key priority of this administration. The relationship between the US and China is underpinned by a growing geopolitical competition. And another point that Irwin makes – and one that we have explored in depth in our work on global fracturing – is that, while trade patterns are shaped by a multitude of factors, geopolitical tensions often lead to a reordering of trade relations.

The first Trump administration represented the start of US pushback against China. This was sustained and broadened under the Biden administration – and its continuation is likely to be a defining feature of the second Trump administration.

In case you missed it:

Ahead of 2025’s first policy meetings of the Fed, ECB and Bank of England Chief Global Economist Jennifer McKeown looks at how accurate central banks are at forecasting interest rates. She’ll be leading a Drop-In this Thursday reviewing the Fed and ECB January meetings and previewing the Bank of England’s decision next week. Sign up here for the 20-minute briefing and explore our policy rate forecasts for major DM and EM monetary authorities on our Central Bank Hub.

China is taking a bigger chunk of market share in low-end industries like tobacco, along with share in high-tech areas such as batteries. Leah Fahy’s groundbreaking new analysis highlights a stunning turn of events in the EM development trends.

Trump’s official declaration that the US is in a National Energy Emergency could reshape global energy flows during his terms but is unlikely to bring down energy prices, our Commodities team argues.