I was visiting clients in the US last week, where the mood felt very different from Trump’s first election victory in 2016 (and when, incidentally, I was living and working in New York). Then, the overriding mood was one of shock. Today, there is less shock and more focus on understanding which of the policies Trump pushed on the campaign trail will make it through to a program for government, and what their economic impact will be. Uncertainty abounds.

The economics of tariffs

Nowhere is this more the case than the president-elect’s potential trade policy. Part of the uncertainty relates to whether the punitive tariffs that Trump has pledged, including a 60% tariff on all imports from China and a 10% universal tariff on imports from other countries, represent a serious threat or a starting point for negotiation. But there is also confusion about the economic impact of tariffs and the channels through which they would take effect.

Economists are trained to think that free trade is “good” and therefore that tariffs are “bad”. Over the long run this is generally true. But it is possible that in the short term, imposing tariffs can boost output in the country that levies them. This is because they can act as an “expenditure switching” tax that diverts demand towards domestic producers.

The problem is that, aside from their level and their coverage, the immediate impact of tariffs will be determined by at least five other things. The first is whether the revenue raised by tariffs is used by the government to either cut other taxes or raise spending. If it is not then an increase in tariffs represents a fiscal tightening that will squeeze demand and therefore output. Assuming that revenue is recycled by the government, the second determinant is whether the impact of tariffs is blunted by moves in exchange rates (this was the case during Trump’s first term in office, when a stronger dollar blunted the effect of the tariffs he imposed.) The third factor that matters is the elasticity of demand for the goods which are subject to tariffs – this determines how likely it is that consumers will respond to the higher cost of the imported good by diverting their spending towards domestic producers. The fourth factor is whether the economy is operating below full employment and therefore capable of increasing output in response to any rise in demand for domestic production. And the fifth, and most important consideration, is whether trading partners respond to US protection by imposing tariffs of their own. Our sense is that governments in most major economies will retaliate in some form but stop short of triggering a global trade war.

All of this means that economic consequences of tariffs are far from straightforward. We suspect that an increase in tariffs under a second Trump administration will lead to a modest one-off increase in US prices and thus a short-lived burst of inflation. They could also accelerate US-China decoupling, since China appears to be the main focus of attention. But if other countries avoid significant retaliation, it is likely that the long-term impact on global trade volumes will be smaller than many now fear.

Likewise, it is a reasonable bet that the Trump administration will fail to deliver on its promise to bring large numbers of manufacturing jobs back to the US. This is partly because the economics of reshoring don’t stack up. Many of these jobs are labour-intensive, and wage costs in US manufacturing are more than 10 times higher than in Mexico and 20 times higher than in Vietnam. Moving jobs back to the US or other advanced economies would push up firms’ costs, which in turn would bleed into higher consumer prices

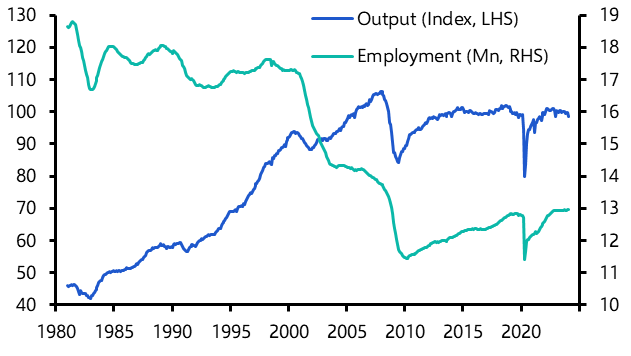

But the loss of manufacturing jobs in the US and other advanced economies is not just the result of low-wage competition from other countries. It is also a function of economic development: as economies get richer and move up the value chain, it makes sense for lower-end production to move to lower-cost centres. Automation has also played a role. This helps to explain why US manufacturing output is higher than it was in 2000, but employment in manufacturing is substantially lower. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: US Manufacturing Output & Employment |

|

|

|

Sources: LSEG Analytics. |

It is possible that some high-skilled manufacturing jobs relocate to the US and other advanced economies over the next decade. But I suspect the numbers will be relatively small, and that the renaissance of manufacturing employment that Trump and other Western leaders promise will not materialise.

Tariffs aren’t the real threat

One area where the economic impact of a second Trump administration could be more significant is immigration. Trump’s early appointments, including Stephen Miller to Deputy Chief of Staff, show an intent to make good on campaign promises to clamp down on both legal and illegal immigration. Those within the president-elect’s transition team have spoken of plans to remove as many as one million undocumented immigrants each year. The economic consequences of this would be potentially substantial.

Immigration has accounted for about four-fifths of the growth of the US labour supply in recent years and has been a key reason why economic growth has kept relatively buoyant, even as the Fed has raised interest rates to generational highs to bring down inflation.

Taken at face value, restrictions on immigration coupled with the active removal of the number of undocumented migrants being discussed could plausibly lower US potential GDP growth by around 1% a year. It is wrong to think of this as solely a hit to the supply side of America’s economy. Migrants spend too, and so demand would also weaken.

But if the pandemic taught us anything it is that the adjustment to new equilibria are rarely smooth, and it is likely that sectors that rely heavily on migrant labour (construction, agriculture, leisure and hospitality) would face a rise in costs that is likely to pass through into higher prices. Taken together, the immigration measures that are being floated would represent a potentially significant stagflationary hit to the US economy.

The rest of the world is naturally focused on the implications of Trump’s trade policy in his second administration, but it’s the president-elect’s intentions around immigration that could prove to be the real hit to the economy.

Note: We’ll be exploring the implications of Trump’s second term in our in-person outlook on the global economy and markets in London on 4th December. Click here to learn about The World in 2025.

In case you missed it:

EM Economist Kimberly Sperrfechter explores what Marco Rubio’s nomination as Secretary of State signals about the outlook for Latin America’s economies in Trump’s second administration.

Our revised FX forecasts in light of Trump’s victory include USD-CNY at 8 and the euro at parity by the end of next year. Explore and download our FX forecasts via this interactive dashboard.

Although German swap spreads – the gap between the 10-year bund yield and the equivalent euro swap rate – recently turned negative for the first time, Chief Markets Economist John Higgins says this market shift is less momentous than it appears.