Harry Truman’s quip about a recession being “when your neighbour loses his job; it’s a depression when you lose yours”, captures many of the difficulties in both identifying when these downturns hit, and how severe they can be. There are crucial distinctions at play here, which go far beyond the market’s binary “recession or no recession” debate and have major implications for how policymakers and investors navigate the fallout.

As the late president suggested, part of the issue is definitional. The crucial idea at the heart of recessions is that there is an element of “reflexivity” to economic downturns. In other words, an initial fall in aggregate demand leads to a rise in job layoffs, which in turn fuels further cutbacks in household and business spending, creating an ever-deepening decline in output that is only broken with the help of policy support.

Recession spotting

The problem lies in the difficulty in identifying any such set of circumstances in real time. In the US, the job of calling a recession has been outsourced to an independent body called the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Its Business Cycle Dating Committee is tasked with deciding when recessions begin and end based on a range of criteria, including industrial production, consumer spending and employment.

This approach adequately captures the concept of “reflexivity” within recessions but comes with at least two drawbacks. The first is one of comparison: other countries don’t have the equivalent of the NBER process, making it difficult to judge whether economies are in recession on a consistent basis. The second is that the data the NBER team rely on are released with a lag and are subject to revision. That’s why it took a year to identify the US recession triggered by the Global Financial Crisis, which started in December 2007.

These challenges have fuelled the search for a simpler definition of recession. US economist Julius Shiskin’s suggestion that a recession be defined by two successive quarters of declining GDP is now widely used. But the simplicity of Shiskin’s definition means that it is at best a rule of thumb, and one that is subject to false-positives and negatives.

This is particularly true in the wake of major shocks, such as that caused by the pandemic. US GDP contracted for only one quarter at the onset of the pandemic (Q1 2020), but the sheer size of the decline in output and the accompanying surge in unemployment meant that the economy was clearly in recession. Conversely, US GDP showed contraction in both the first and second quarters of 2022, but nobody seriously believes that the economy was then in recession. If nothing else, payroll employment rose by 2.7 million in the first half of 2022.

Recession seismology

So identifying recessions is hard. But the scale of the downturn in a recession is also an important qualifier: there is a vast difference between a 2007-08-style recession, whose effects persist for several years, and a 2001-style recession that is over before you know it. Distinguishing between different types of recession and identifying their likely consequences is therefore more important than simply making a recession “call”.

Broadly speaking, recessions come in four flavours. The first is caused by shocks from left field that start by hitting the supply side of economies. The pandemic is a good example, as are the oil shocks of the 1970s. The loss of output in these recessions can be extreme and may only be partially offset by policy loosening, but activity tends to recover sharply once supply problems ease.

|

Supply Shock Recession |

Balance sheet Recession |

Cyclical Recession |

Growth Recession |

|

|

Example |

COVID, 1970s oil shock |

Global Financial Crisis, Great Depression |

2001 US recession, early 1990s UK recession |

DM weakness in mid-1990s |

|

Cause |

Supply-side shocks: war, pandemics, energy shocks, drought |

Asset price collapses requiring extended periods of balance sheet repair that weigh on private sector demand. Housing bubbles particularly painful. |

Demand weakens in response to policy tightening, creating feedback loops into employment, and back into consumer and business spending. |

Multiple, including monetary or fiscal policy tightening, deterioration in terms of trade, and weakness in export partners. |

|

Policy response |

Monetary and fiscal policy insufficient beyond cushioning subsequent weakening in demand. |

Substantial: large interest rate cuts, possibly QE, large fiscal stimulus. |

Moderate: rate cuts but no QE, some fiscal stimulus. |

Modest: small rate cuts, fiscal support through automatic stabilisers but little discretionary stimulus. |

|

Effect |

Large loss of output. Quick recovery once supply problems resolve. |

Large and persistent loss of output. GDP often fails to return to pre-crisis trend. |

Moderate loss of output, GDP returns to trend, no permanent loss of output. |

GDP doesn’t fall but remains below trend for several quarters, causing unemployment to rise. |

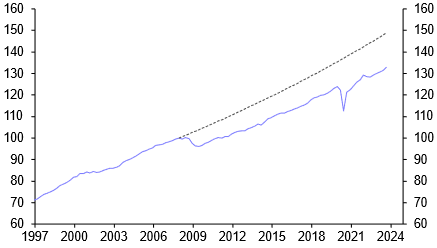

The three other types of recession are caused principally by developments on the demand side of economies. The most extreme involves asset price collapses and financial crises. These are often precipitated by excess credit growth and the development of asset bubbles, the most damaging of which has historically been in housing. Once these bubbles burst, balance sheet recessions ensue and the loss of output is substantial. Central banks and governments loosen policy substantially, but the fallout from the crisis frequently damages supply potential and means that GDP often fails to recover to its pre-crisis trend. This was the case in the 2007-08 recession. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: US GDP (Real, Q4 2007 = 100) |

|

|

| Source: Capital Economics |

The second type of demand-driven recession is a cyclical or plain vanilla recession. These typically follow periods of policy tightening that are aimed at staunching excess demand or inflation problems. A good example is the early 1990s recession in the UK. In these kinds of recession, the loss of output tends to be modest, the degree of subsequent policy loosening is more moderate and the eventual recovery is more complete, with GDP typically returning to its pre-recession trend.

The final type of recession is known as a ‘growth recession’. In these, economies continue growing, but so slowly that unemployment rises. There is no loss of output in absolute terms, but GDP falls below potential, which causes disinflation pressures to build and living standards to be lower than would otherwise have been the case. Growth recessions can have many causes, ranging from a deterioration in a country’s terms of trade to the effects of policymaking. For policymakers, the difference between being confronted by a growth recession or a mild cyclical recession is often more luck than judgement.

Recession forecasting

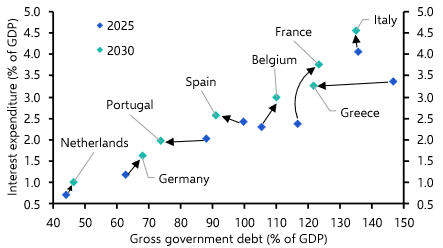

The absence of large financial imbalances or strains in household balance sheets suggests that a major recession of the type experienced in 2007 is highly unlikely. Cyclical recessions are a bigger risk in countries where central banks have raised interest rates to well above their neutral level and where fiscal policy is playing less of a support role. We think these are more likely than not to emerge in the euro-zone and UK over the next year, but also stress that they will be relatively mild.

The chances of a cyclical recession in the US are high but perhaps no more than 50-50 at this stage given the continuing support from fiscal policy. However, a US growth recession, in which GDP growth slows sharply for several quarters, looks extremely likely.

The most important question in all of this is what is needed for inflation to fall back to target. In theory, all three types of demand-led recession should generate disinflationary pressures, albeit to differing extents. And, as we have stressed before, the easing of pandemic-era supply constraints means that it’s possible that inflation could fall sharply with only a modest weakening in demand pressures. A mild form of growth recession could therefore be enough to return inflation to target in most countries – a view vindicated by US CPI data released last week.

When it comes to calls for 2024, perhaps the biggest and most important of them all will be that inflation is likely to be back or close to target by the end of the year.

What you may have missed:

Javier Milei’s victory in Argentina’s presidential election brings shock therapy onto the table. See our dedicated election page for all of our key insight into Milei’s economic platform.

Following signs of a thaw in US-China relations, Senior Markets Economist Tom Mathews explored the implications for “risky” and “safe” assets. See our fracturing dashboard for a visual guide to the global economy in the shadow of eroding bilateral relations.

Our US team explained why we think the Fed will cut rates much more aggressively next year than markets are pricing in.