Transcript:

Andrew Kenningham:

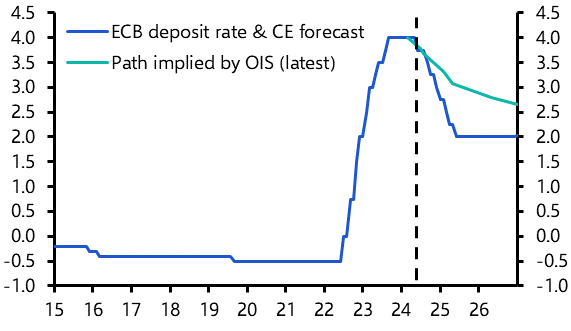

It's Friday, 31st of May and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm Andrew Kenningham, Chief Europe Economist. I'm standing in for David Wilder this week, who's having a well-earned two-day break. And I'm joined by my colleague Jack Allen-Reynolds for this special preview of the ECB's June meeting. So this meeting on Thursday is shaping up to be quite momentous. Not so much because there's any doubt about what the ECB is going to do with interest rates – a 25 basis point cut has been really well signposted. But because it marks the beginning, hopefully, of an ECB easing cycle, it's also the first of the three major Western developed markets and central banks to be making a cut. The Fed, we think, will not cut until September at the earliest and the Bank of England, perhaps in August. So before we start talking about the detail of the meeting, let's just take a step back and think about where the ECB has come from. So it's a 25-year-old institution and it's had its interest rates on average at 1%, I was just checking, and it's had interest rates at zero or below zero for a full 10-year period leading up to 2022. So since then, they began raising interest rates in July 2022, that was a bit later than the Fed and the Bank of England, and lifted the deposit rates to what was a record high of 4% last September. So assuming they do cut on Thursday, rates will have been at that peak level for nine months. In the meantime, inflation has come down from double digit levels to below 3%. So we'll get into a lot more detail on the inflation in a minute. But now turning to you, Jack, maybe you could explain why we and other analysts are so confident that the ECB is going to cut rates on Thursday.

Jack Allen-Reynolds

Well, we're so confident that the ECB is going to cut rates because they've more or less told us that's what they're going to do. It seemed that policymakers reached an agreement at their last meeting in April to cut at this meeting in June, and all the comments we've heard since then suggest that that's still their view. Now, of course, it could be that since then, some policymakers now think that it would be better to leave interest rates unchanged, but central bankers being central bankers, they're concerned about their credibility, and they don't want to be seen to be saying one thing and then doing another. So even if they thought they should leave rates unchanged next week, then they might well go ahead with a cut regardless. But I think taking a step back and looking at the fundamental reasons why the ECB is going to be cutting interest rates, well, inflation's fallen a very long way from its peak. At its highest, it was just over 10%. It's now just over 2%. So there's less of a need for interest rates to be so far into restrictive territory. And if we look back to September 2023, when the ECB implemented its final rate hike, several policymakers at the time described that as an insurance hike. So they're taking out insurance against the risk of a wage price spiral. So wage growth and consumer price inflation spiralling upwards together. Now that the inflation rate is much lower than it was then, that risk of a wage price spiral is much lower. And so the ECB arguably no longer needs that insurance.

Andrew Kenningham

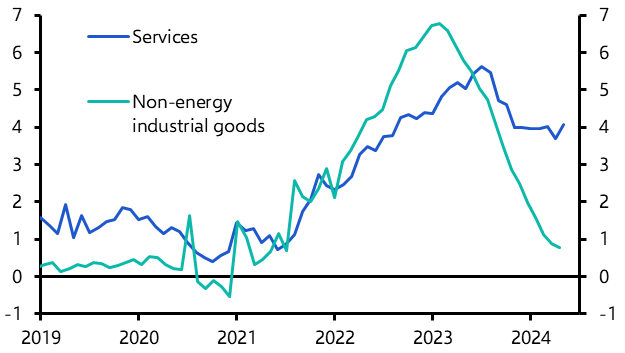

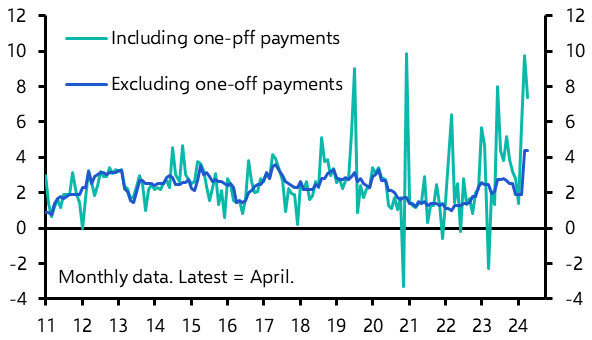

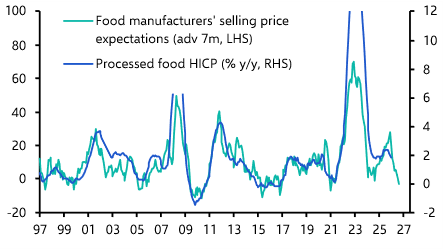

Yeah, exactly. I mean, it's interesting, or perhaps I should say it's a bit ironic, that over the last few weeks, most of the data that have come out have actually been pretty negative from an ECB point of view. We saw, in fact, in the May inflation data that were published on Friday, both the headline and the core rate rose by 0 .2 percentage points. And perhaps most worrying, the services inflation rate rose from 3 .7 % back up to 4 .1. Now it had been stuck at 4 .0 % for many months, I think since last November, and we'd been worried about when it was going to start falling. That then did go down in April only to rebound in May. Now we had anticipated an increase because there were some Easter effects and some changes in public transport ticket prices in Germany that were pushing the number around, but we had not expected the increase to be quite that large. So I think had those numbers come out earlier or had the ECB not pre-committed to this June rate cut, it's very likely that they would have said “well, let's wait a few more weeks for July and see if some of these numbers sort of rebound or come drop back again in the June numbers”. And the other thing that's worth talking about a bit is the wage data. The ECB officials back in March made a very big deal out of importance of wage data. They got us all scrambling around and looking at all sorts of unusual measures of wage inflation because they were saying that is the single most important thing that will determine whether or not they cut rates in the summer. In fact, the negotiated wage data rose in Q1 relative to Q4, that is the rate of inflation of negotiated wages rose, and partly that was down to some one-off effects in Germany where there was a big cash payment that was not taxed in March for a lot of public sector employees. But we then learned that the compensation per employee inflation rate also went up in Q1. Not very much, but still it was moving in the wrong direction. So generally there's a bit of a sense that the labor market is not easing as quickly as central bankers would have liked.

Jack Allen-Reynolds

Well, yes, I think the ECB is ultimately concerned with consumer price inflation.

And at the moment, it's putting a lot of emphasis on services inflation, because that's one of the most reliable guides to domestic price pressures. So those are the prices that the ECB has most control over through monetary policy. And the rate of services inflation in May was very strong. Now, if you look into the detail of the services inflation data over the past six to nine months or so, it's possible to identify a number of what might be seen as one -off effects have kept services inflation high. But obviously, at some point, if you have a long period of one-off effects, it becomes harder to dismiss services inflation. It looks like something more fundamental is going on. And I think what fundamentally is going on is that wage growth is still quite high, and that's keeping services inflation high. Now, in the eurozone, there are lots of different measures of wage growth. And the more you know about the data, the more you realize that you don't know. And all of those different measures don't necessarily point in the same direction. But I think if we try to look through the noise, I think the big picture is that wage growth was still quite strong in Q1. But wage growth is past the peak. So it does seem to be on the way down. It's just falling very slowly. And that's because the labor market is still quite tight. And after workers have taken big real-terms pay cuts over the past few years, they now want to see a catch-up in their real spending power. So they're going to want to see wage growth outpace inflation for a period. And that's going to mean that wage growth stays high probably through this year and absent to next year too. But as wage growth gradually comes down, services inflation should also gradually come down too. And that should in time give these be enough confidence to continue cutting interest rates.

Andrew Kenningham

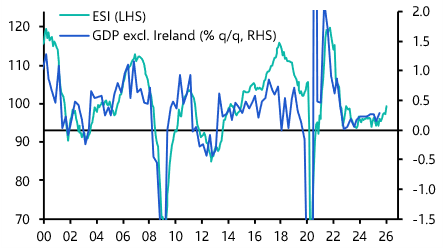

Yeah, exactly. I think that one of the interesting things I read from one of them, 26 governing council members over the recent weeks is a speech and there was an interview as well by Philip Lane, the Chief Economist, about the outlook for wage growth and inflation. What I found interesting was that in the entire speech, he talked about the wage price process as being really rather backward looking, where as you say, inflation rose first and then wage growth picked up because people were trying to catch up in terms of their real wages. We're now seeing sort of third round knock on effects because services inflation is rising a bit because that's because wages have been so strong. So this process has got nothing to do with a conventional Phillips curve where you have a, an assumption that inflation is primarily driven by output gaps or, or the economy running slightly above potential or below potential. That whole model, which is you learn a sort of basic economics textbooks doesn't seem to be in play which means you're left trying to guess how quickly wages and prices will settle down to a more normal rates of change. And I think it's reasonable to assume they will slow despite the labor market being quite tight, but very hard to judge how quickly. We haven't yet spoken about how we think things will evolve in terms of policy beyond June. Now we've just made a change ahead of this meeting, taking out a rate cut that we had assumed would be coming in July as well as the June one. So we no longer think they'll do back to back rate cuts just because this latest data has been a bit stronger than anticipated. But because we do think the underlying disinflation process is still going on, albeit a bit more slowly than previously anticipated, we still have significant rate cuts over the rest of this year with three more in the autumn in September, October and December, which would bring the deposit rate down to three percent. I mean, I think the risks to that are that we would have to take out another 25 basis points from that projection. But I think on balance for now, that's a reasonable view. Inflation, even core inflation, is not that far above the target now, and it does seem to be gradually trending downwards. Beyond next year, harder to say. I mean, maybe Jack, you could talk through views on where the neutral rate is and why we have our forecast that rates ultimately settle as near a 2%.

Jack Allen-Reynolds

Yes, well, we published a large piece of work on neutral real interest rates, which is available to subscribers on our website. But in terms of the eurozone, the key point there is that our estimate of the neutral level of policy rates in the eurozone is about two and a half percent. Now we're forecasting the ECB's deposit rate to bottom out at two percent. So that would mean monetary policy moving into accommodative territory.

Andrew Kenningham

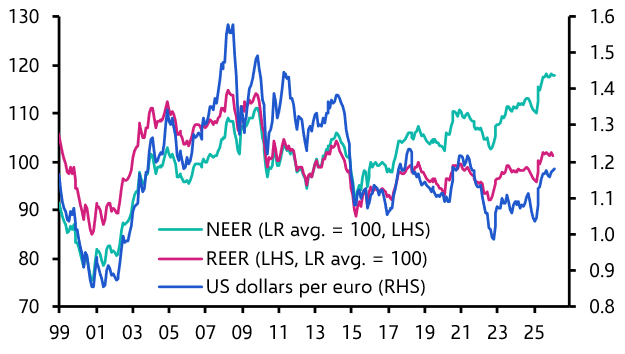

Okay, so let's now turn to the sort of broader international situation. I mentioned earlier that the ECB is moving ahead of the Fed and the Bank of England. That was a subject of discussion some months ago, would the ECB even be able to go before the Fed? I think that was a little bit of a contrived debate. I mean, we've seen the ECB move before the Fed in the past. One of Christine Lagarde's quite nice phrases was that the ECB is “data dependent, not Fed dependent”. But there is a genuine question about how far the two central banks could diverge. I think it's worth thinking through what the linkages are between rates in the States and over here. Well, I think the concern would be that if the US Fed keeps interest rates unchanged at a high level at the same time as the ECB is cutting interest rates, that would cause the euro to weaken significantly, and in turn that would push up inflation in the eurozone. I think that's the concern, but the reality isn't quite as simple as that. The historical association between interest rate movements and the exchange rates is very loose. There are lots of other things that affect the value of currencies other than interest rates. So a weaker euro in principle could push up inflation in the eurozone, but acting in the opposite direction, tied to monetary policy in the US, all else equal would mean higher bond yields in the US, which in turn, all else equal would mean higher bond yields in the eurozone. So that would mean tighter financial conditions in Europe and lower inflation in the eurozone. So you've got those two effects working in opposite directions. And I think if we take a step back and look through history, the ECB and Fed have diverged significantly in the past. There have been very big differences in policy rates on either side of the Atlantic. And that's just been entirely dependent on the state of the eurozone economy and the state of the US economy. So if price pressures are weaker in the eurozone, then the ECB will cut interest rates and it'll have a lower level of interest rates than in the US. So ultimately, the ECB is not setting policy in a vacuum, but I don't think its hands are tied by what the Fed's doing.

And it is not possible to put a number on how much further the ECB could go with rate cuts than the Fed, because interest rates are simply not the only thing that affect the value of currencies.

Jack Allen-Reynolds

Yeah, it's worth adding that the two effects that you mentioned, the exchange rate effect and the effect via the bond market are both genuine, but they're both probably quite small. I think we were estimating that 10% fall in the currency in nominal effective terms might boost headline inflation by 0.4 % or something. So really not that significant, particularly when policymakers need to look through that in any case, because they're trying to target inflation a couple of years in the future. So I think, yeah, some significant divergence is perfectly plausible.

Andrew Kenningham

Right. Well, I think we should wrap up there and continue our preparation for the meeting on Thursday. Thank you very much, Jack, for joining me. Jack and myself and the rest of the team will be doing a Drop-In. That's one of our short form online briefings, a little bit after the Thursday decision to answer all of your questions and highlight any key takeaways from the communications. We'll include the registration details on the podcast page and we'll add a report previewing the meeting and some recent analysis of wage dynamics and inflation. But in the meantime, goodbye.