A flurry of data and policy announcements in recent weeks has provided more clarity about where the global economy is heading, even as it has highlighted some key risks to that outlook.

Three things have become clear. The first is that the global economy is holding up reasonably well, albeit with significant divergences between the performance of individual countries and regions. According to our estimates, world GDP expanded by 1.5% q/q in Q1 compared to -0.4% q/q in Q4. However, this comprises a boom in China (with output up 7% q/q in Q1 according to our China Activity Proxy measure of output), a slowdown in US GDP growth to 0.3% q/q (or 1.1% annualised) and broad stagnation in Europe. Most strikingly, the UK economy is still 0.5% smaller than it was at the start of the pandemic and roughly the same size as it was in mid-2019. With that said, despite having experienced a huge hit to its terms of trade from higher energy prices, Europe – including the UK – has so far managed to avoid falling into recession.

The second thing we have learned is that inflation is proving to be worryingly sticky. Headline CPI edged down in the euro-zone in April, but core inflation edged higher. At the same time, core CPI in the US increased by another 0.4% m/m. Favourable base effects as last year’s big monthly increases in energy and food prices drop out of the annual comparison will bring down year-on-year rates of inflation over the coming months. But the month-on-month increases in prices are still uncomfortably high for central banks and inconsistent with 2% inflation targets.

Finally, we have learnt that, despite this, central banks are starting to believe that they may have done enough to get inflation down to more acceptable rates later this year. The Federal Reserve raised interest rates by 25bps to 5.00-5.25% at its meeting earlier this month, but signalled that this would be the last hike in the cycle. The Bank of England sent a more equivocal message when policymakers met last week, but it may also have reached the end of its rate-hiking cycle. And while policymakers at the European Central Bank believe they have a bit more work to do, they slowed the pace of tightening from 50bps to 25bps at their meeting this month. We have nudged down our forecast for the peak in euro-zone interest rates from 4% to 3.75%.

The three questions that frame the outlook for DMs

So much for the past, what should we expect going forward? The outlook for the major advanced economies is framed by three questions. The first is how much the cumulative effect of policy tightening over the past year now causes economic growth to slow. The second is the extent to which this in turn causes inflation to moderate. And the third is whether central banks remain in control of the process, or whether they will be overwhelmed by a sudden and disorderly tightening of financial conditions caused by either problems in the banking system or a shock from elsewhere (such as a failure to agree a deal to lift the federal debt ceiling in the US).

Answers to these questions require judgements that are complicated by the fact that pandemic-related distortions have made this an extremely unusual cycle.

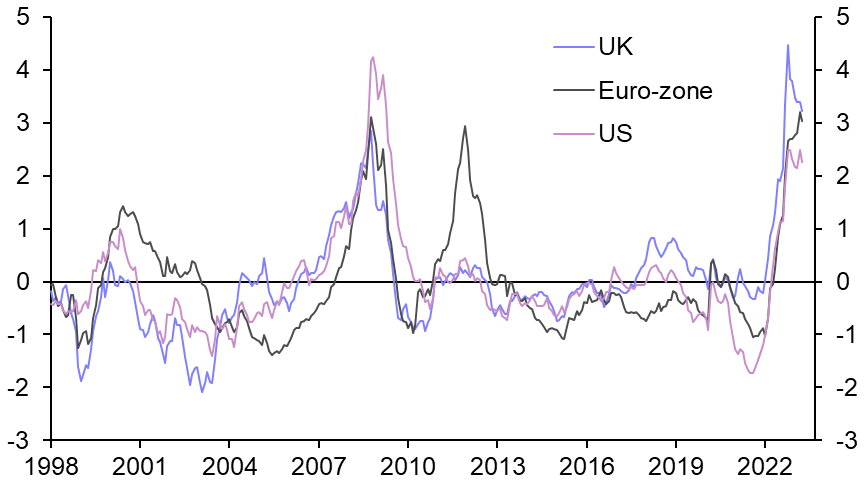

We still expect most major advanced economies to fall into recession this year. Financial conditions have tightened substantially across developed markets over the past 12 months, and history shows that this feeds through to the real economy with a lag. (See Chart 1.) Indeed, our analysis suggests less than half of the effects of monetary tightening so far have been felt in the real economy. In every cycle there comes a point where the economy appears immune to the effects of tighter policy – only for growth to rollover and recession to become a reality.

|

Chart 1: CE Financial Conditions Indices (Z-scores) |

|

|

| Sources: Capital Economics |

As tighter financial conditions bite, we expect most major advanced economies to slip into recession and wage and price pressures to cool. Leading indicators are already pointing to a relatively sharp slowdown in US wage growth. (See Chart 2.) That in turn means that it’s too soon to rule out interest rate cuts by the Fed this year – although rate cuts in the UK and euro-zone are unlikely until 2024. With all that said, the recessions we are forecasting are relatively mild and should probably qualify as soft landings given the extreme run-up in inflation over the past year.

|

Chart 2: Job Quits & Employment Cost Index |

|

|

| Sources: JOLTS, Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

What could still go wrong?

There are two main risks to this view. The first is that household savings accumulated during the pandemic means consumer spending remains resilient in the face of tighter policy, or that inflation doesn’t respond to weakening demand. As I’ve noted before, our old Phillips Curve-based models of inflation have broken down in recent years, meaning that it is extremely difficult to judge the response of wages and prices to changes in demand and to calibrate policy accordingly. It’s possible that central banks may ultimately have to tighten further to get inflation under control.

The second risk again relates to how successfully central banks manage policy to meet their goals. The latest Senior Loan Officers Survey provides some reassurance that US credit conditions haven’t dramatically tightened so far as a result of bank failures – although they do remain extremely tight. And comparisons that have been drawn between the current problems in US regional banks and the global financial crisis in 2007-08 are misplaced. But as dominos continue to fall, it’s not difficult to see how this could translate into a further sharp tightening of lending in the real economy.

Investors should draw two lessons from all of this. First, it’s extremely difficult to calibrate policy tightening at the top of most cycles, but pandemic-related distortions mean that it is particularly challenging in this one. Second, whichever way you cut it, the current calm in markets seems unlikely to persist – either recessions will become a reality, which will knock corporate earnings and equities, or inflation will prove stubbornly high, which will force central banks into additional policy tightening that is not being priced by the bond market.

On balance, we think recessions are the more likely outcome.

In case you missed it:

- Deputy Chief US Economist Andrew Hunter and Deputy Chief Markets Economist Jonas Goltermann discussed the likely outcomes, workaround solutions and market impact of the latest standoff over raising the federal debt ceiling in our latest podcast episode.

- We’re tracking Turkey’s election and its associated economic and market risks on our dedicated election page. As we had forecast in the run-up to Sunday’s vote, a second round run-off now looms.

- The Economist’s cover story this week draws heavily on our analysis, captured in this 2018 report, about the structural and political headwinds that would lead to a dramatic slowdown in Chinese trend growth.