The tariff storm is far from over. President Trump and some of his key officials used the weekend to dig in their heels on his ‘Liberation day’ tariffs, and European and Asian markets have fallen heavily again on Monday while S&P 500 futures point to another grim day for the US.

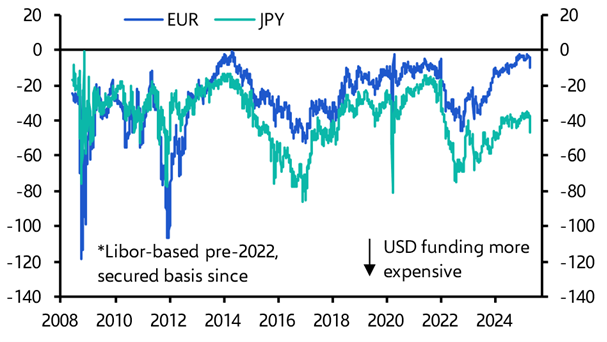

Falls of this speed and scale can become self-reinforcing as margin calls are triggered. They can also lead to unanticipated consequences. The biggest risk is that the market dislocation more generally leads to a rise in counterparty risk that either causes something in the financial market plumbing to freeze or something in the system to “break”. A good barometer of this is “cross currency basis”, which is a gauge of stress in international funding markets. This has increased in recent days, but is still relatively low. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: 1y Cross-Currency Basis (bps)

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

It’s the dollar, stupid

Over the medium-term, movements in the foreign exchange markets will play a key role in determining the economic consequences of tariffs. The textbooks suggest that in a world of floating exchange rates, the dollar should appreciate following the imposition of US tariffs (since demand for imported goods – and therefore foreign currency – should fall). But the dollar has weakened by more than 6% since Trump began rolling out his protectionist trade agenda after being sworn back into office, with the falls accelerating since ‘Liberation Day’.

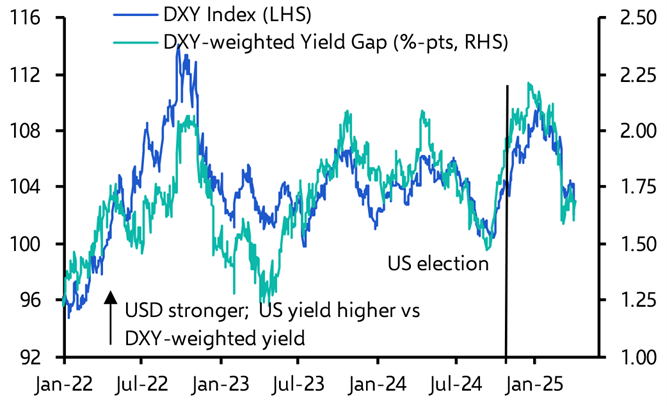

One theory for the weakness is that the scale of these tariffs, and the manner in which they are being forced on the world, has shaken investor faith in the credibility of US policymaking and its institutions. If so, then the dollar is now behaving more like an emerging market currency. But the more straightforward explanation is that tariffs of this size and scope are a clear and present danger to the health of the US economy and, in the face of this threat, investors are pricing in a substantially lower path for the fed funds rate. This is borne out by the strong correlation of the dollar’s moves over the past week with the interest rate differentials between the US and some of its leading trading partners (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: DXY Index & DXY-Weighted 5-Year Government Bond Yields

Sources: IMF, Capital Economics |

All of this matters because moves in exchange rates have a critical bearing on the economic effects of tariffs. A stronger dollar would blunt their impact for both the US and the rest of the world, because tariffs make US imports more expensive and a stronger dollar makes them cheaper. But a weaker dollar would exacerbate the effects of tariffs – magnifying the hit to both the US and its key trading partners.

Assessing the damage

All of this underscores the challenges inherent in trying to quantify the economic costs of tariffs. As well as currency moves, the effects on growth and inflation in the US and other countries will be influenced by four factors: a) the size of the tariffs imposed on each country, and the dependence of that country on exports to the US (and, for the US, the size of its imports from that country); b) whether these tariffs are permanent or whether governments can successfully negotiate them away with the Trump administration; c) whether and how the tariff revenue raised by the US government is recycled in the form of offsetting tax cuts or increases in spending; and d) the extent to which each country retaliates by imposing tariffs on the US. China’s response has been much more aggressive than anticipated and makes a near-term deal to end the trade war between the two superpowers unlikely.

The various factors at play mean estimates about the impact of tariffs carry a high degree of uncertainty. If the tariffs remain in place at announced levels, and the retaliations by other countries are relatively limited, then they could knock around 0.3-0.4% off GDP in the euro-zone and 0.1% off GDP in the UK. The impact on Asian economies – which were hit with much higher tariffs – will be larger. We think they could lower Japanese GDP by around 0.4%, Korea’s by 0.6% and lower China’s GDP by 0.8%.

In practice, and despite the administration’s apparent intransigence, it is still a reasonable assumption that tariff rates are ultimately negotiated lower in exchange for concessions – though the baseline 10% tariff seems likely to stay, and tariffs on China are likely to remain much higher. If they do come down then the economic costs will be smaller, though still significant. In the US, inflation is likely to head north of 4% y/y later this year and growth could slow from around 3% q/q annualised at the end of 2024 to around 1% q/q annualised by the end of this year. The probability of a US recession may have risen to something like 30%, but rising inflation will reduce the scope for insurance cuts by the Fed.

Shifting sands

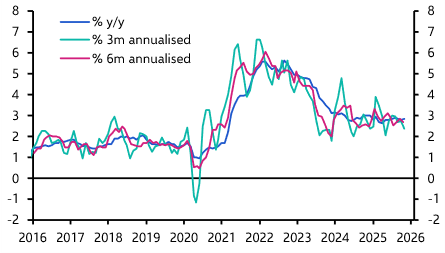

Stepping back from the recent turmoil, it’s clear these tariffs mark Donald Trump’s most aggressive attempt yet to break from the post–World War II era of economic liberalisation that has shaped the global economy. When – and if – these tariffs take effect on 9th April, the average US tariff rate will stand at 24%, just above the rate that followed the signing of the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3: US Effective Tariff Rate

Sources: LSEG, Capital Economics |

But key elements of the globalised world are likely to prove resilient. Despite Trump’s boasts, only a fraction of the manufacturing that has moved overseas is likely to move back to the US. Not only would shifting production be enormously expensive, but the decision-making that informs how companies locate production facilities requires years of thinking and it’s unclear where tariff rates will be at the end of this week, let alone at the end of this decade. In some areas, for example toys, textiles and furniture, the cost advantage of emerging economies is so huge that even large tariffs don’t make the US competitive.

Furthermore, this is not a global trade war similar to that which engulfed the world economy in the 1930s. Other countries haven’t been following the US and raising tariffs on each other in recent weeks. This is a risk, and we will argue in a report this week that if Chinese exporters shift sales from the US to other large markets such as Europe then a protectionist backlash could follow. But we’re not there yet.

And it’s also worth remembering that globalisation was always about much more than just international trade in goods. It means trillions of dollars in cross-border services trade and investment flows, millions of people moving around the world for work and countless other interconnections and interdependencies among countries.

The structures of globalisation have deep roots – they are being tested by this administration, but there are reasons to believe that they will for the most part outlast it.

In this context, much will depend on how far countries can go in negotiating lower tariffs. While US tariff rates are unlikely to return to their previous levels, allies like Mexico, Canada, the UK, and Japan – yes, the US still has allies – may have more success in easing trade barriers than rivals such as China. If so, the more likely outcome is a fractured world economy, not a fully deglobalised one.

In case you missed it:

Chief US Economist Paul Ashworth explored potential paths ahead, including the economic impact of the baseline 10% tariffs on imports into the US – but also what happens if Trump stays the course with higher rates.

We held a Drop-In shortly after news of China’s retaliation on Friday. Click here to watch a recording of the online briefing about Beijing’s calculus, what the EU might do, and how markets are responding.

Our Asia team’s early estimate of the impact of Trump tariffs lays bare the implications for economic growth across the region.