The past few weeks have brought a flurry of data and speeches from central bankers. What have we learned about the health of the global economy and the outlook for monetary policy?

It’s important not to place too much weight on a single data point, particularly when statisticians are grappling with a broad decline in response rates to the underlying surveys. Markets will inevitably respond to the daily ebb and flow of data but as a rule of thumb we would wait for three months of data to separate signal from noise. With this in mind, three points stand out:

1. The US economy remains on a much stronger footing than every other major advanced economy

The post-COVID era remains one of US macro exceptionalism. Admittedly, after a turgid 2023, other advanced economies now seem to be turning a corner. The UK has returned to growth following a brief (technical) recession in the second half of last year and Germany’s economy posted a large increase in industrial output in March (albeit on the back of large falls in January and February).

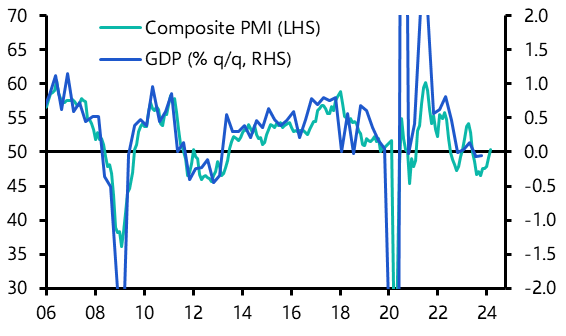

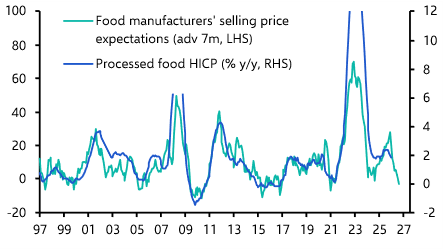

But the broad story remains one of US outperformance. We expect data released this week to show that the US economy grew by 2.5% q/q annualised (or 0.6% q/q) in Q1. In contrast, the monthly data are consistent with UK GDP growing by about 0.3-0.4% q/q (or 1.2-1.6% q/q annualised) in the first quarter and euro-zone GDP being broadly flat. (See Chart 1). Measured over a long period, the outperformance of the US is even more stark. Since the middle of 2022 US real GDP has increased by around 4.5%, while real GDP in the UK and euro-zone is broadly unchanged.

|

Chart 1: Euro-zone GDP and monthly activity data (% q/q) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

Several forces are driving faster growth in the US, including the fact that potential growth itself is higher than in Europe. But short-term fluctuations in growth are usually driven by developments on the demand side of economies. There are two key differences between the US and Europe on this front. First, the prevalence of 30-year fixed rate mortgages means that US households were able to lock in low interest rates during the pandemic era and therefore shield themselves from the effects of Fed tightening. And second, fiscal policy is providing greater support to demand in the US.

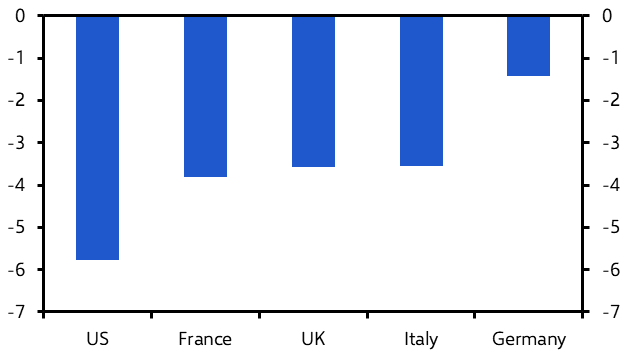

According to IMF data, the primary budget deficit – that is to say the deficit excluding interest payments – was 5.8% of GDP in the US last year. That compares to primary deficits of around 3.5% in the UK, France and Italy and 1.4% in Germany. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2: Primary Budget Balance (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

Sources: IMF, Capital Economics |

At some point, US fiscal policy will need to be tightened. The timing and the scale of the necessary fiscal adjustment will depend on the ability of the US government to retain the confidence of the bond market. For now, though, the support provided by fiscal policy appears to be a key reason why aggregate demand in the US – and economic activity – is so much stronger than in other advanced economies.

2. The latest inflation data are a concern – but there’s no reason for central banks to panic (yet)

There are two important rules when analysing inflation data: be aware that the convention of reporting inflation in year-on-year terms (i.e. the price level compared with this time last year) often says more about what was happening several months ago than right now, and understand what goes into the measure of inflation you’re looking at.

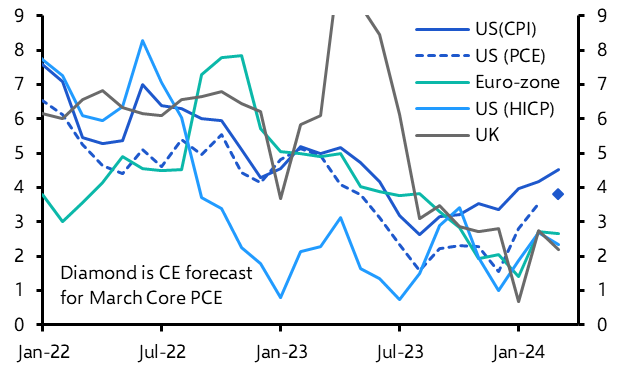

Depending on which measure you use, the three-month annualised rate of US core inflation in March was either 4.5% (core CPI), 3.8% (our estimate for core PCE), or 2.3% (core HICP). (See Chart 3.) This variation is a function of differences in the coverage and composition of each index. The current wedge between core CPI and core PCE reflects differences in the way that the price of motor vehicle insurance and health care is accounted for. And the reason that core PCE and core CPI are higher than core HICP is because housing and shelter – which has been remarkably resilient in recent months – has a larger weight in both.

|

Chart 3: Core Consumer Prices (SA, % 3m annualised) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics. SA series estimated from 1998. |

Core PCE forms the basis of the Fed’s inflation target but the measure that is comparable with the euro-zone is core HICP. The consensus view is that inflation is running hotter in the US than in Europe. But measured on a consistent basis inflation is actually running at similar rates in both regions. This is an important point and one that isn’t getting enough attention in the global debate about where inflation is heading.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean that there are no causes for concern on the inflation front. In the US the three month-annualised rate of core PCE is clearly picking up. Meanwhile, in both the euro-zone and UK core services inflation – which both the ECB and BoE follow closely – surprised on the upside in March. And a rise in global energy prices over the past month has also rekindled concerns about a renewed pick-up in inflation in advanced economies.

However, as noted earlier, the strength of core PCE is partly due to the resilience of the shelter, which is a lagging component that alternative measures suggest should start to fall back over the coming months. Likewise, the strength of services inflation in Europe may be due in part to the timing of Easter this year. And while higher global energy prices are unhelpful, the rise over the past month or so is likely to add only 0.1-0.2%-pts to headline inflation in developed economies.

The disinflation process was never going to be a smooth one. Inflation has not slowed quite as much as we had anticipated in the past couple of months but there’s no need to press the panic button just yet.

3. There are good reasons for the ECB and the BoE to cut rates ahead of the Fed

All of which brings us to the policy response by central banks. Getting policy forecasts right in the post-Covid era has depended on three things:

- Getting the outlook for growth right (made more challenging by important role played by changes on the supply side of economies);

- Understanding how inflation dynamics in this cycle (if it can be called that) are different and, related, that the pass-through from growth to inflation has been obscured by the death of the Phillips Curve; and

- Gauging the “reaction function” of central bankers (made more difficult by the fact that the weirdness of this cycle has compromised their own forecasts).

Viewed through this lens it makes sense that the Fed will push back rate cuts to later this year: growth is strong; inflation on the Fed’s preferred measure hasn’t slowed as much as expected; and officials have probably been spooked by the concerns about the stickiness of inflation. Absent an economic shock, there’s no rush to cut.

Conversely, there’s a good case to consider cutting in the UK and, in particular, the euro-zone. Growth in these economies is weaker, inflation is closer to target, and having chased the Fed up there’s a risk that policy will become too tight as more households and firms refinance fixed rate debt (remember that this is a bigger risk in Europe than the US).

Concerns that the ECB or BoE need to wait for the Fed to cut are overdone. Both have moved independently of the Fed in the previous cycles. Developments on the inflation front have muddied the waters, but we still expect the Fed, ECB and Bank of England to cut interest rates by more than markets are currently pricing in over the next 18 months. And we think the ECB and BoE will move in June – even if the Fed now waits until September to make its first move.

In case you missed it:

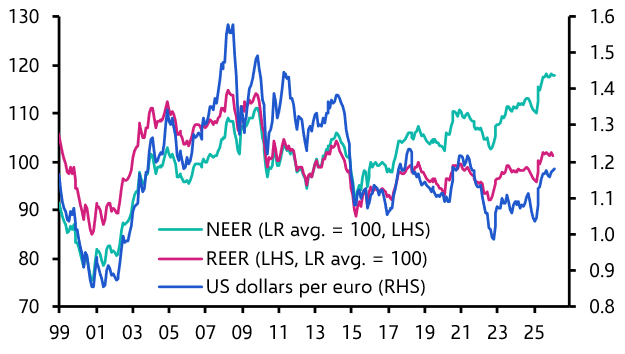

Our Europe team looked at currency weakness and rising energy prices as potential roadblocks to ECB rate cuts. They’ll be making their case for the Bank to lower rates by 125bps this year in a Drop-In this Thursday.

With the US Treasury yield curve on its way to a record run of inversion, Deputy Chief Markets Economist Jonas Goltermann explored how this episode may differ from previous.

South Africa’s economy may finally be turning a corner, says Africa Economist David Omojomolo, though it may not come soon enough to save the ANC’s electoral chances.