The big takeaway from the first Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and Bank of England meetings of 2024 is that policymakers will not be pushed into cutting rates any time soon.

Policymakers in China appear to be in a similarly cautious mood. The People’s Bank of China finally delivered a cut to reserve requirement ratios (RRR) late last month, but the scale of the move was small in the grand scheme of things and an initial boost to investor sentiment and the equity market quickly reversed.

While policymakers in the US, Europe and China are united in their caution, they are facing very different challenges. In the US and Europe, the primary focus remains on bringing inflation to heel – although, as I noted last week, the monthly price data paint a more encouraging picture on this front, and figures released since suggest that policymakers in Europe should be focussed more on the extreme weakness in domestic demand seen in data from the end of last year. The ghost of Arthur Burns continues to haunt central bankers across advanced economies.

China’s inflation picture is very different. Monthly consumer and producer price data due this Thursday are both likely to present more evidence of deflation, and overarching concerns about the weakness of Chinese activity persist. This is where things get tough for both policymakers and investors alike.

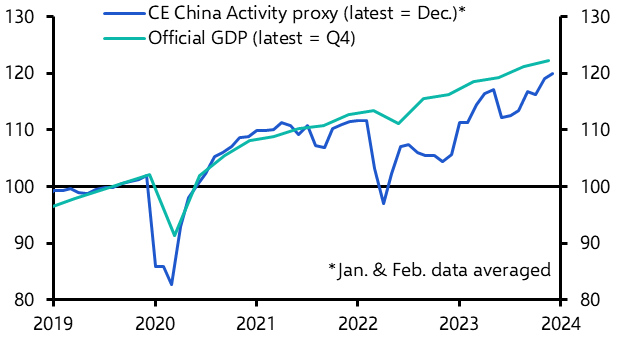

The problem, as ever, is that the quality of official GDP data means that it’s hard to get a clear read of what is actually happening on the ground in China. The National Bureau of Statistics says the economy lost momentum in the fourth quarter, with real GDP growth slowing to 1.0% q/q from 1.5% q/q in the third.

However, we are sceptical that growth was ever that strong in Q3. Our China Activity Proxy (CAP), which provides an alternative view of output without having to rely on official data and has a track record dating back almost 20 years, suggests that the economy contracted in Q3 before returning to growth in the fourth quarter. This is consistent with the low-profile data that show that increased fiscal support helped to shore up activity towards the end of last year. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Capital Economics China Activity Proxy & Official GDP (2019 = 100, seas. adj.) |

|

|

|

Sources: CEIC, WIND, Capital Economics |

It is nonetheless clear that China’s economy has struggled over the past year. Having rebounded after the lifting of zero-COVID at the end of 2022, the economy stalled around the middle of last year and, according to our CAP, output is now broadly where it was at the end of the second quarter last year.

Cuts to the reserve requirement are unlikely to do much to reinvigorate growth. This adjusts the amount of liabilities (and therefore assets) commercial banks can hold for a given level of reserves at the central bank. Lowering the RRR allows commercial banks to expand their balance sheets and increase the supply of loans to households and businesses. But unlike in the past, the binding constraint on lending in China is not the supply of credit – it is subdued demand.

Even if cutting interest rates promised to do more than give the economy a short-term boost, concerns about exchange rate stability appear to be deterring the PBoC from substantially reducing borrowing costs. Speaking after the RRR announcement, Governor Pan Gongsheng repeated the official line about aiming to keep the renminbi “basically stable”. Worries about financial stability risks caused by another rise in private sector debt may also be contributing to policymakers’ reticence to cut interest rates.

At the heart of this dilemma is the structural, rather than cyclical, nature of China’s growth problem. This is an economy reaching the limits of its high-savings, high-investment model. Investing up to half of GDP is difficult at the best of times, but particularly when China’s capital stock is now relatively advanced for its level of development and the state is playing an even greater role in determining the allocation of resources. This makes generating returns on investment extremely difficult.

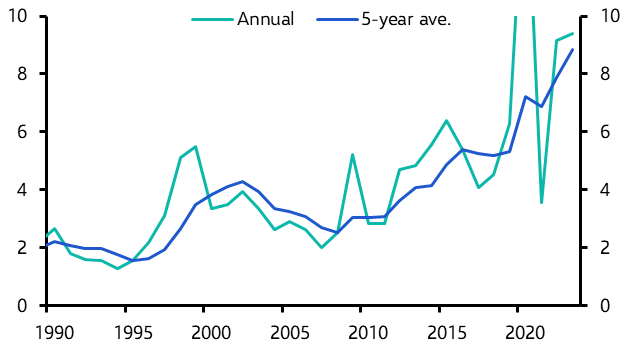

China’s incremental capital-output ratio – a measure of how much investment is needed to generate an additional unit of GDP – has soared in recent years as investment has become increasingly inefficient. (See Chart 2.) The counterpart to this is a drop in productivity growth which, when combined with demographic pressures, is pulling down long-run potential growth.

|

Chart 2: China’s Incremental Capital Output Ratio |

|

|

|

Sources: CEIC, Capital Economics |

Policy loosening, including RRR cuts, interest rate reductions, and fiscal support, works by stimulating demand. But any improvement in demand would quickly run into the reality of China’s structurally weaker supply. The solution lies in a programme of structural reforms that rebalance China’s economy away from investment and allow the market to do more work in terms of allocating resources. But our recent assessment of China’s reform efforts highlighted just how little progress has been made and concluded that rebalancing is still a distant prospect. A painful adjustment now looms.

With inflation apparently in retreat, the Fed and other central banks face a difficult judgment in knowing exactly when to cut interest rates. But reviving China’s economy is an altogether more challenging proposition.

In case you missed it:

John Higgins reviewed US big tech firm valuations following a slew of earnings releases to see how they stack up against our 5,500 end-2024 call for the S&P 500.

Jack Allen-Reynolds explored how the euro-zone economy is likely to fare in the face of a stringent fiscal tightening exercise.

After Egyptian policymakers appear to have taken steps to pull the economy out of its crisis, James Swanston discussed what more is needed to get the country on a stable footing.