Having spent the past year worrying over runaway inflation in the major advanced economies, markets are now having to contend with the apparent threat of deflation in China.

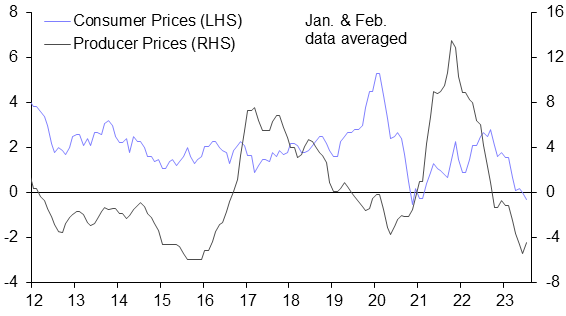

July’s 0.3% y/y fall in China’s consumer price index and 4.5% y/y drop in producer prices (Chart 1) have stoked fears about chronic demand weakness in the world’s second largest economy. Equity markets and commodity prices fell on the news, but have since regained their footing, in part because of hopes that the signs of deflation will prompt an injection of policy stimulus by Beijing.

|

Chart 1: Consumer & Producer Prices (% y/y) |

|

|

| Sources: Capital Economics |

Misreading the data

However, the response to the price reports may be a classic case of the markets – and the commentariat – misreading the data and drawing the wrong conclusions. The big fall in the headline CPI rate was driven by a fall in food prices. Consumer prices in China have been strongly affected in recent years by swings in pork prices, which surged due to a heatwave last year but have since fallen back. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, they declined by 26% y/y in July.

Meanwhile, core inflation – which strips out food and energy – rose from 0.4% y/y in June to 0.8% in July. And services inflation rose to a 17-month high of 1.2% y/y. (See Chart 2.)

|

Chart 2 : Services & Core Goods CPI (% y/y) |

|

|

| Sources: Capital Economics |

As I noted last week, the links between output and inflation are not always well understood and changes wrought by the pandemic have undermined the usual relationships between real economic variables and prices. China’s inflation dynamics are particularly unusual. A growth model built on a high rate of domestic savings and investment will tend to produce very low rates of inflation. Accordingly, falls in the headline inflation rate are not that uncommon – the annual rate of CPI was negative as recently as February 2021. (See Chart 1, again.)

But the key point is that, to the extent that chronic demand weakness shows up in the inflation data, it will do so in the core numbers and in particular in the services numbers. After all, these are the parts of the inflation basket that are most likely to be influenced by domestic conditions.

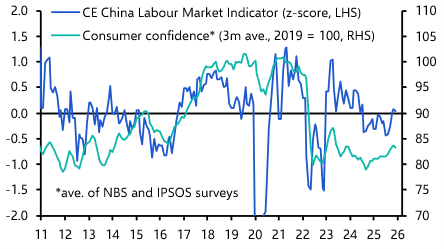

To be clear, both core inflation and services inflation are still low by international standards. Moreover, it is also clear that China’s economy is struggling. According to our China Activity Proxy, output fell a seasonally-adjusted 1.4% m/m in June. The extent to which China’s post-COVID recovery has fizzled out becomes obvious when we look at levels (rather than growth rates) of output. (See Chart 3.)

|

Chart 3 : China GDP and CE China Activity Proxy (Q4 2019 = 100) |

|

|

| Sources: Capital Economics |

However, the fact that some measures of underlying price pressures have edged up at a time when the economy is struggling suggests that economic weakness may not be due only to the cyclical weakness of demand – structural problems may also be playing a role.

A more troubling conclusion

We have written at length about the factors that will contribute to a slowdown in China’s potential growth rate over the coming years. One is the country’s demographic challenges. China’s population began falling last year and early estimates for births in 2023 suggest that even the UN’s low fertility scenario, which projects an average population decline of 0.3% per year over the next decade, could prove too optimistic. At the same time, a combination of over-investment and a reluctance to let the market do more of the work in allocating resources will contribute to a slowdown in productivity growth. The problems faced by the developer Country Garden over the past week are emblematic of the challenges facing China’s property sector more generally. Taken together, we have argued for a while that China’s trend rate of growth will slow to just 2% by the end of this decade. But the fact that the post-COVID rebound has fizzled out so quickly without a corresponding drop in underlying price pressures could be a sign that China’s potential growth has slowed more quickly than even we had anticipated.

If that is the case then the market – and policymakers – risks drawing the wrong lessons from the recent slew of data. The primary issue may not be a cyclical weakness of demand that can be remedied by policy support. Instead, it seems more likely to be chronic supply-side problems that will pull down China’s growth rate over many years and can only be addressed through structural reforms rather than monetary and fiscal stimulus.

A combination of policy support and base effects mean these latest signs of deflation in the official numbers will be likely gone before year-end. China will be living with its structural supply-side issues for a lot longer.

What you may have missed

Our Asia team recently discussed whether the Chinese economy is in a ‘balance sheet recession’ in an online briefing. Watch the recording here.

As more EM central banks prepare to cut rates, Senior EM Economist Liam Peach explained what to expect in terms of the magnitude and speed of monetary easing.

Global Economist Ariane Curtis argued that fiscal policy might be making central bank jobs harder.