Weeks of speculation have been building to the moment at midday DC time today when Donald Trump will, for a second time, place his hand on the Bible and swear to faithfully execute the office of the president.

His return to the White House should finally start to bring clarity to the enormous uncertainties facing the global economy and financial markets around how much of Trump’s rhetoric, both on the campaign trail and as president-elect, will become governing reality.

Despite a flurry of recent reports about what Trump is planning for the opening days of his presidency, as of now nobody really knows what’s coming – the only real certainty is that the path ahead in markets is likely to remain bumpy.

Tariffs aren’t necessarily the boogeyman

There are a few areas where we can be reasonably sure about what to expect. First, it is likely that tariffs on US imports will be increased, although when, by how much or on what goods and countries remains unclear. Based on Trump’s rhetoric, we have assumed that the US will impose a 60% tariff on imports from China and a 10% universal tariff on imports from other countries, albeit with the potential for carve-outs for certain goods such as energy. (All our key analysis on what to expect in Trump’s second term can be found on this dedicated page.)

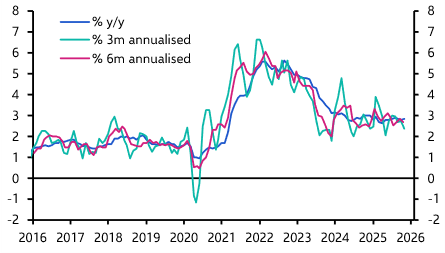

While higher tariffs do not make for good policy, the economic consequences are often exaggerated. The impact will depend on several factors, including the size and scope of the tariffs, the degree to which the dollar appreciates in response, and the extent of retaliation by other countries. Taken together, we think that higher tariffs could push US CPI inflation above 3% y/y by the end of this year but, since this represents a one-step shift in the level of prices rather than the start of successive increases in prices, the effect should be temporary and inflation should drop back in 2026. And while Mexico, Canada and China could be hit relatively hard by those tariffs (perhaps shaving 0.5-1.0%-pts off their respective GDP) the impact on other economies, including those in Europe, is likely to be modest.

Over the longer term, the bigger issue is the extent to which the imposition of tariffs leads to a material deterioration in relations between the US and its traditional allies. One of America’s strengths in a fracturing world is the extent of its alliances with, and influence over, both major developed economies and several large emerging markets. This has made it easier for Washington to reconfigure supply chains away from China in areas deemed to be of strategic importance. It has also helped facilitate the imposition of broad controls on exports of cutting-edge technology to China from the West. If Trump’s more adversarial approach weakens America’s alliances it will undercut one of its key advantages over China in a fractured world.

A stagflationary foreign worker crackdown

Curbs on immigration are also undoubtedly coming early in the life of the new administration, although their impact on migrant flows and the extent to which the government will remove undocumented workers are also unclear. That means their economic consequences are equally uncertain. All other things being equal, efforts to reduce net migration to the US and remove undocumented workers will squeeze the supply of labour. This will in turn reduce potential GDP. But since migrants also spend, aggregate demand will also be weaker than would otherwise have been the case. The consequences for inflation are therefore more ambiguous than many assume. It’s also important to note that immigration to the US has already slowed substantially over the past six months. Our sense is that the effects of immigration reform will be mildly stagflationary, although a lot will hinge on the scale and timing of policies in this area.

All roads lead back to fiscal policy

While tariffs and immigration reform have hit the headlines, the Trump administration’s approach to fiscal policy is arguably the more important issue. As we have noted elsewhere, the US fiscal position is in a significantly worse place now than when Trump first took office in 2017. The federal budget deficit is near 7% of GDP and net debt is running at close to 100% of GDP. On top of this, the shift from negative to positive real interest rates has made the arithmetic that underpins US public debt dynamics extremely challenging. At current interest rates and even assuming GDP growth remains close to its recent solid pace, the US would have to undertake a fiscal squeeze equivalent to 3% of GDP to stabilise the ratio of federal debt-to-GDP. That limits the room for additional deficit-financed tax cuts. Accordingly, if Trump is to make good on campaign promises to cut taxes on everything from tips to corporate profits then these will have to be funded either by increases in other taxes (such as tariffs) or spending cuts. Either would represent a shift in the burden of taxation or spending in the economy rather than additional fiscal stimulus that would boost aggregate demand.

Stepping back, many of Trump‘s stated objectives actually require a tightening of fiscal policy. For a start, all other things being equal, a tighter fiscal stance would reduce both the current account and trade deficits. And since it would allow monetary policy to be loosened, it would also help to weaken the dollar and provide support for US exports. Indeed, starting with a blank piece of paper, I would argue that fiscal consolidation should lie at the heart of the next administration’s economic plans.

Conversely, if the administration is intent on pushing through additional deficit-financed tax cuts, then the adverse consequences could be significant. They would not only widen America’s current account deficit and, in the short-term at least, contribute to an even stronger dollar (since monetary policy would have to be correspondingly tighter). But they would also threaten a swift and severe reaction in bond markets that would tighten financial conditions and weigh on activity.

The post-Global Financial Crisis era has been dominated by the actions of central banks: their dramatic cuts to interest rates and the expansion of their balance sheets through asset purchases have set the tone in markets, while fiscal considerations have taken a back seat. This is starting to change. Whatever the new administration brings, its actions (and inactions) in fiscal policy will have a significant bearing on outcomes over the next four years.

In case you missed it

Our US team is holding a special post-Inauguration Day Drop-In to answer your questions and discuss what we’ve learned so far. Register here for Tuesday’s 20-minute online briefing and join another session on Wednesday all about what Trump’s return means for Mexico.

The Shape of the Fractured World in 2025 presents our latest analysis and data on the emergence of competing US and China-led economic blocs.

With a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas now in effect, our latest MENA Weekly explored implications for the region’s economies while this note showed what the end of fighting could mean for Israel.