Capital Economics is 25 years old. Founded by Roger Bootle in 1999, the company has grown from a handful of employees (and clients) to a global enterprise which today provides macro and market insight to tens of thousands of decision-makers across business, finance and government. Since anniversaries are a good time to reflect, Neil Shearing and senior colleagues this week consider the big themes that have shaped the global economy over the past 25 years and – more importantly – assess how they are likely to play out over the next 25.

Neil Shearing on globalisation – and what comes next

25 years ago, the prevailing view in governments and boardrooms was that globalisation was a path to prosperity, profits and peace. Tariff and non-tariff trade barriers were slashed. Restrictions on cross-border investment flows were loosened, particularly in emerging economies. And, while governments retained controls on labour flows, immigration increased steadily through the 2000s. The global economy was reshaped. Supply chains multiplied as technology and politics pushed firms to locate production on the basis of efficiency. Global trade increased from around $7.5trn in 1999 to over $25trn in 2019, with cross-border investment flows trebling over the same period. Globalisation helped keep a lid on inflation in advanced economies and was central to emerging economies rapidly catching up. Average incomes in emerging markets were about 10% of the G7 average in 1999. Today that figure is close to 25%.

But it’s generally accepted that the era of hyper-globalisation has now ended, even if there’s no consensus on what will follow. Our view is that the world is fracturing into two blocs: one that aligns primarily with the US, and another that aligns with China. Governments will come under pressure to pick a side. And policy decisions and economic outcomes within blocs will be shaped increasingly by geo-political considerations. This is not globalisation in reverse. Indeed, our analysis suggests that large swathes of global trade will be unaffected by a fracturing US-China relationship. But fracturing will nonetheless transform the global landscape over the next 25 years. Governments will face difficult trade-offs between promoting economic efficiency and safeguarding national security. Multinational firms and international investors will face a more uncertain operating environment in which political considerations play a greater role in decision-making over economic outcomes. The impact in sectors where there is a strong national security interest – like chipmaking, AI and advanced manufacturing – will be profound.

- Neil Shearing is Group Chief Economist. He joined Capital Economics in 2006.

Mark Williams on China’s growth and reform struggles

The past quarter century has transformed China economically – and yet it’s back in a strikingly similar place. At the National People’s Congress in March 1999, then-Premier Zhu Rongji warned of a “grim” economic situation. A key prop for the economy – state-owned industry – was collapsing following a government push to get a grip on its soaring debt. The financial system looked at risk of sinking beneath a sea of non-performing loans. The aftermath of the Asian Financial Crisis was still being felt. And while the official GDP data said the economy was growing rapidly, some analysts thought it was barely expanding at all. China was just over a year from finalising its entry into the WTO, but there wasn’t much optimism at the time.

In drawing lessons for today’s Chinese economic situation, there’s the optimistic take that the consensus views on the medium-term outlook are often just extrapolations of the recent past. They miss turning points. Perhaps China is due another turn in the cycle soon. Another take – closer to ours – is that China’s success in the years after 1999 was contingent on a supportive global environment and on policies that either can’t or won’t be repeated: WTO entry and the surge in manufacturing that it catalysed; the creation of a private property sector during a period of rapid urbanisation; and relaxation of state control over large parts of the economy that allowed the wider private sector to boom. The global environment is becoming more hostile, residential property is now in decline, and structural weaknesses are not being addressed. We expect China’s potential growth rate to slow to just 2% by the end of this decade.

A final lesson from the past 25 years is that an economy’s performance doesn’t necessarily determine how its markets perform. China’s economy is nearly seven times the size it was in 1999 according to the GDP data (five times the size according to our China Activity Proxy). The MSCI China index is 4% higher.

- Mark Williams is Chief Asia Economist. He joined Capital Economics in 2007.

Paul Ashworth on the death and rebirth of inflation

The past 25 years has seen global inflation swing from one extreme to the other. In the 2000s, price inflation was just right – US PCE inflation averaged 2.1% over the decade – but asset price inflation ran riot, with the bursting of the housing bubble eventually bringing the global financial system to its knees. That set the scene for the next decade, when US PCE inflation ran too cold, averaging only 1.5% in the 2010s. Deflation became the major threat. With most major central banks powerless as interest rates became stuck at the zero nominal bound, the fear was that advanced economies were only one recession away from following Japan into a debt-deflation spiral. Structural forces also conspired to keep inflation low, with globalisation and technological progress generating a decade-long decline in goods prices.

Nevertheless, by 2017 we were worrying that the balance of risks was tilting back toward inflation running too hot and the excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus during the pandemic, combined with the disruptions to supply, left us convinced that higher inflation had become the biggest risk.

PCE inflation has averaged 3.9% in the 2020s, almost double the target. However, it now appears to be rapidly returning to the 2% target. With inflation expectations also normalising, we expect inflation to remain around target levels over the next few years. Despite this ‘Goldilocks’ environment, we suspect that structural forces, including US-China fracturing and the effects of climate change, will make inflationary supply shocks more common. This will mean that inflation becomes more volatile, and that overshoots of central banks’ inflation targets will become more common than undershoots.

- Paul Ashworth is Chief US Economist. He joined Capital Economics in 2001.

Vicky Redwood on the fall – and rise? – of productivity growth

25 years ago, hopes were high for a productivity growth boom on the back of the ICT revolution. The reality was disappointing. The US aside, ICT-related productivity gains were far from spectacular and, in some cases, failed to materialise at all. Even in the US, productivity growth slowed again from the mid-2000s. In fact, there has been a lot of head-scratching among economists for most of the past couple of decades about why the productivity record, of developed economies in particular, has been so dismal. Are the current hopes about the productivity benefits of AI another case of misplaced optimism?

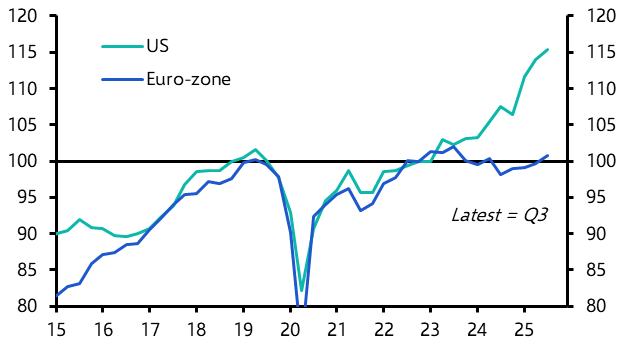

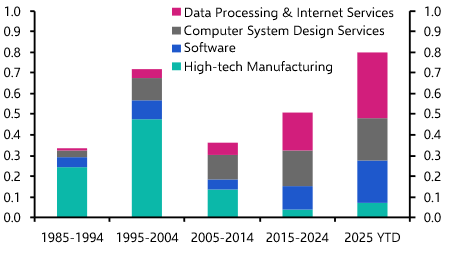

Yes and no. We do believe that AI has the potential to drive a significant increase in productivity via efficiency gains and aiding innovation. But, as happened with past technological breakthroughs, we think that it will take several years for infrastructure and processes to adapt to this new technology. So, an imminent “big bang” of productivity gains seems unlikely; instead, the boost will come through gradually during the late 2020s and 2030s. Another lesson from the past is that productivity gains from technology are by no means guaranteed and will depend on whether economies have the factors in place to help them utilise the technology. The US will be the main beneficiary; we expect productivity growth there of 2% a year in the 2030s. This will widen its outperformance over the euro-zone. And if we are right that AI will boost productivity in advanced economies more than emerging ones, this will amplify the slowdown in the rate at which average emerging market incomes are catching up with developed market ones.

- Vicky Redwood is Senior Economic Adviser. She joined Capital Economics in 2003.

John Higgins on the recurrence of bubbles

It looks to us as if Capital Economics’ first quarter of a century will be bookended by big bubbles in the US stock market. Back in the late 1990s, investors were seeking to crystallise the future benefits of the internet. Today, they’re doing something similar with AI. Yes, the valuation of the S&P 500 is stretched now by the standards of most of the past. And yes, the index is top-heavy because it’s been propelled by a handful of tech behemoths that are perceived to be some of the biggest potential winners from this latest transformative technology. Yet, the valuation of the S&P 500 is still a fair bit lower than it was at the peak of the dot com bubble. And, if you compare the ratio of the 100 biggest firms in the index to the rest, it became even more top-heavy back then. This suggests to us that the AI bubble could inflate a lot more. Indeed, unlike those commentators who expect a tougher year for the S&P 500, we forecast that it will rise to 5,500 by the end of 2024. What’s more, we suspect the index will continue to climb in 2025 – our end-year forecast is 6,500 – before the bubble inevitably bursts.

Unlike the bursting of the other big bubble in the lifetime of Capital Economics, which was in real estate, the bursting of the dotcom bubble didn’t bring the global economy to its knees. We doubt the bursting of the AI bubble will either. And just as the bursting of the dotcom bubble didn’t sound the death knell for the internet, we don’t expect the eventual bursting of this latest bubble to do so for AI.

- John Higgins is Chief Markets Economist. He joined Capital Economics in 2008.

Click here to see more on the 25th anniversary of the founding of Capital Economics.