Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 3rd of May and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, the advanced economy central bank that may raise rates at its next meeting, and no that's not the Fed, and where prices of key commodities are heading. But first, Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist, joins me to do a post-mortem of the week in macro markets gone by and an ultrasound of the week to come. Hi there Neil, how's it going?

Neil Shearing

Hi David, good, and you?

David Wilder

Yes, striking end to the week, isn't it? We've had another payroll surprise. Markets are moving on the release, but this time it's different. Tell us about that US April jobs report and what it means in terms of the Fed meeting gone by. Does it give the kind of confidence that Powell, etc. say they need before they can consider cutting rates?

Neil Shearing

Well, it was just the tonic that markets needed at the end of the week, I think, and the Fed and other central banks, including the Bank of Japan, will be breathing a little more easily. So not only was the payrolls number a bit softer than expected, the consensus was for a 243,000 increase in payrolls. Our forecast was at the bottom end of the consensus range at plus 200,000. Actually, it was 175,000, so softer, still reasonable, but softer, but also modest tick up in the unemployment rate and the rate of growth of average earnings slowed 2.2% month on month. So just about everything that the Fed wanted to see here. Softer, but not disastrous. And I think it goes a long way to reinforcing the message that Powell was giving on Wednesday after the FOMC meeting, which was that the bar to rate hikes is very high.

We've talked like this before, haven't we, on the podcast. I said that I thought it was extremely unlikely that the Fed would be hiking interest rates as some had started to speculate. Well, Powell's comments and now this payrolls report, I think goes a long way to show them why that's the case. So I think it takes rate hikes off the table if anyone was anticipating them. I don't think it necessarily brings rate cuts onto the table. The Fed's going to need to see more data in this direction and probably a further slowdown in payrolls growth and a bit more of a pickup in unemployment before it starts to consider cutting interest rates. But it does underline the fact that the data are choppy, things can turn around quickly as we head into the second half of the year, I suspect rate cuts will start to come back onto the table.

David Wilder

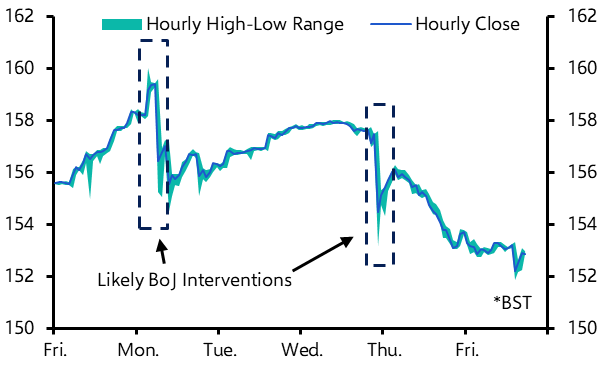

You mentioned just then the Bank of Japan breathing a bit more easily, dollars off quite sharply in the wake of that payrolls report. Talk about that yen intervention story which started the week, still no confirmation from the Japanese authorities, but the yen is ending the week a good deal stronger than where it started it. Given all you've just said, is the Bank of Japan and Ministry of Finance off the hook?

Neil Shearing

Well, as I've said before, I think there are three components really to a successful currency intervention as we think about how the Bank of Japan's responded. The first is that it's got to be pretty large. The second is that it's normally more successful if it is coordinated with other central banks. And the third is that it fits in with the broader thrust of monetary policy, doesn't go against the grain of monetary policy shifts. Now, when we think about what the Bank of Japan's done over the past week or so, you say, it's not yet confirmed, but it looks like from the data that we're tracking, we've had two quite substantial interventions by the Bank of Japan, possibly amounting to about $60 billion worth of FX sales. So that would be pretty substantial. So it ticks the first box. It's not really coordinated in the sense that the Fed's not done anything and other central banks have not intervened either. So it's not really a coordinated move. So second box is unchecked. And then the third point is this idea that it needs to fit in with the broader thrust of monetary policy. The fundamental issue, of course, is the interest rates in the US far higher than those in Japan, and that's putting pressure on the yen. Well, the payrolls data that we've just had is only one piece of data, but it's helped to push down the yield curve in the US, narrow some of that rate differential with Japan, take some of the pressure off of the yen. So Banks Japan gets a big tick for the scale of the intervention by the looks of things. The data seem to be helping out too, but I think we're going to need to see more data go in the Bank of Japan's way, that is to say, pointing towards rate cuts in the US at some point, in order for the end to be out of the woods.

David Wilder

And Chinese renminbi for that matter as well, I presume. But let's turn to the coming week's big events. Bank of England is possibly the biggest meets this Thursday. Give us a quick preview of what we're expecting from that meeting.

Neil Shearing

Well, it's extremely unlikely that the Bank of England adjust interest rates at this meeting, but all eyes will be on whether or not it signals a rate cut coming in June, at its next meeting in June. It's possible and indeed we think given the fact that inflation is likely to fall a bit further than the bank expects over the coming months, it's probably likely. However, it's also worth acknowledging that when you look at the latest batch of data over the past month, they've gone against the bank really. So, CPI inflation was a bit stronger than the bank's forecast. CPI services inflation in March was also a bit stronger than the bank was expecting. At the unemployment rates, employment's coming a bit lower than the bank had expected. And of course, GDP in Q1 was a bit stronger too. So the data go in a bit against the idea that the bank might cut in June, but we anticipate a slightly larger forwarded inflation than the most. So I think it's too soon to take that off the table. I think one point that's worth stressing is that it's not always the case that the bank actually signals changes in the interest rate cycle ahead of them actually happening. So if you look back to 1997, when the bank was first given independence, there's been 12 changes in the interest rate cycle since then. Of those, the bank flagged only five in advance, and it flagged only two more than one month ahead or one meeting ahead.

So the market will be looking for signals that the bank is gearing up to cut rates in June. If we don't get those signals, it doesn't necessarily mean that a rate cut in June is altogether out of the question though. It will depend on the incoming inflation data, I think.

David Wilder

I'd like to take a step back because although we talked about the dollar weakness that we've seen this afternoon, Friday in London, it is still pretty strong relative to levels of late. We've spent a long time on this podcast, haven't we? Talking about strong US markets, strong US growth, but at the same time talking about issues around Chinese underconsumption and European stagnation. And this all seems to tie in with this idea that the US economy has been powering ahead while other major economies struggle. Is this something that is set to continue? And really, what are the macro market implications if so?

Neil Shearing

Well, I think that's the key point that the strength of the dollar, to a large extent, is a reflection of the strength of the US economy. In the past, when we've had a strong dollar,

It's gone hand in hand with a deterioration in external competitiveness of the US economy. We've seen a substantial widening of the US current account deficit. So for example, in 2007. This time around, while the real trade weighted dollar index has appreciated, we've not seen a deterioration in the US current account position. It's running a deficit of about 3 % of GDP that compares to about 6 % of GDP deficits in 2006.

And the reason for that, if you dig beneath the surface, is that the non -energy trade deficit in the US as a share of GDP is larger than it was at the time of the last big concern about global imbalances in 2006. So we've seen a deterioration in the non -energy trade deficit. But the energy balance has gone from a deficit of around 2 % of GDP to a small surplus. So this really reflects the fact that the US has gone from large net energy importer to a net energy exporter. The US balance of payments position is therefore strengthened. That supported the broader economy, but also the dollar. So it comes back to this point that the strength of the dollar reflected the relative health of the US economy. And that's a big difference from previous periods of dollar strength.

Now there's lots we can get into here and indeed it's something that we're going to be covering in our annual Spotlight Report which we'll be publishing in early June. That will cover not just the near -term outlook for the US economy and how it stacks up against its peers, but also how that's likely to evolve over the medium term, what it means for financial markets and also what it means for the US's place in the world in its relations with other economies.

David Wilder

Staying on global themes Xi Jinping is going to be starting a visit to Europe as this podcast goes out on Sunday. It's his first in five years and it's a trip that's taking place against a backdrop of rising tensions about Chinese exports, in Europe's case around electric vehicles and the imports from China. From a macro perspective, how should we be thinking about this trip in the broader context of rising tensions about trade, but also the story that we've been telling about a fracturing world economy?

Neil Shearing

Yeah, I think it's a key element actually, Europe's place in that story about US-China fracturing, where it sits and how governments in Europe respond. Now it's pretty clear as the world fractures into US and China -led blocs, Europe will align far more naturally with the US. We've seen that over the past two or three years, particularly in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. But I think by the same token, Europe's really been a bystander so far in the fracturing debate. It's not trying to project itself as a world leader in the same way that the US is. Rather, it's been dragged along and dragged into fracturing by the US and frankly by Russia's actions too. So it's been slightly more passive, I would say, so far. Now, one implication of that is that the policies adopted by European governments will depend to a large extent, I think, on the pressure placed on them by the US. The US election is going to be really critical in all of that. Will the US bring Europe along with it and create a greater counterweight to China's emergence as a geopolitical rival? Or might the US start to alienate Europe as a key partner? You can imagine that happening if Donald Trump was to, for example, get back into office and restart trade wars with Europe. So the US -Europe relationship is as important in all of this as the Europe -China relationship. The other fact that I think is a bit different is that Europe, of course, is a combination of different sovereign countries. Within that grouping, there are a couple, Serbia and Hungary that stand out as having distinctly warmer relations with Beijing. When we updated our fracturing map late last year, we moved Hungary from close US ally to lean US and we put Serbia as the only country in Europe leaning towards China. So there are a couple of countries within Europe that have warmer relations with Beijing and

Of course, Hungary is important in that regard because it's a member of the EU, has huge Chinese investment particularly in battery technology. Perhaps not coincidentally, Serbia and Hungary are two countries that she's visiting along with France. So it's a slightly more complicated political position in Europe. And of course, Germany has stronger economic relations with China too, that it will be keen to protect. So there's lots of competing pressures on European governments. I suspect we'll start to see some of those play -outs over the coming days as Xi's visit progresses. But I think a key point is that it's not just about the EU -China relationship, it's also about the pressure brought to bear by the US on European governments as the fracturing between US and China evolves.

David Wilder

That was Neil Shearing talking about global fracturing, the latest on inflation in central banks and the question of US economic supremacy. That spotlight project that Neil mentioned is going to be out in the first half of June. It's going to include in -depth analysis, interactive data resources, in -person and virtual events across North America, Europe and Asia, and of course special podcast. So watch out for all of that. Details to follow.

Global Economic Fracturing was our spotlight theme for 2022, but the point of all of these Spotlight projects is that they mark the beginning of a stream of coverage on these issues. Our Fracturing page, which are linked in the podcast page, gives you a sense of how we track the involvement of these issues, what it means for macro, what it means for markets, with output from across the economist team. That fracturing page also includes the interactive map that Neil mentioned. You'll see which way Serbia and Hungary lean, but you'll also get a visual sense about what this fractured global economic system actually looks like. For more on the yen, take a look at our FX Markets weekly wrap. It's their end of the week guide to everything that's happened and everything that's coming in the weeks ahead. There's a lot of takeaways about the yen's moves in that report, and I'll put it on the podcast page.

On China trade tensions, the latest export and trade balance data is out of Beijing this coming Thursday, so look out for our coverage of that. Thursday is also that Bank of England meeting and our UK team will be holding a drop -in, that's one of our short -form online briefings, shortly after the decision to make their case for a rapid fall in UK inflation and more aggressive rate cuts than the markets are pricing that's 10am New York 3 o 'clock London on Thursday registration details on the podcast page and on our events page capitaleconomics.com/events. A subscription to CE Advance, our premium platform, means you get access to all of these drop ins all of our analysis all our data resources plus a host of engagement tools so you can talk directly with our economist team find out more about CE Advance at capitaleconomics.com/ce-advance.

Now, staying on central bank decisions, the Bank of England may signal rate cuts at its meetings coming week and we think Sweden's Riksbank could actually cut rates when it meets on Tuesday. But not all advanced economies' central banks are in the mood to consider easing. Take the Reserve Bank of Australia. It meets on Tuesday and our ANZ team thinks there's a case for the bank raising interest rates expectations at the start of this year were for the RBA to be part of the global easing cycle. But as Abhijit Surya from our ANZ team explained to me, the data coming out of Australia in recent months have upended those expectations.

Abhijit Surya

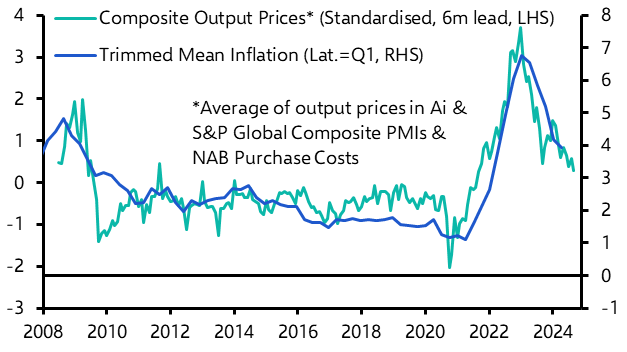

So at the start of the year, we were very much in the mainstream because we too were saying that the Reserve Bank of Australia would cut interest rates rather than hike them. But clearly the slew of upside surprises in the recent data suggest that the bank will have to change its tune. And that's why we're forecasting another rate hike at its upcoming meeting, even though it's admittedly a minority view. So talk a bit about what's happened in the data, what you've been seeing that's made us change our view. So I would say there were a couple of big surprises in the data recently. The first thing is that inflationary pressures are clearly much stronger than we and the RBA had anticipated. And I'm not talking about headline inflation that has broadly evolved as expected, but it's actually underlying inflation, which is what the RBA really cares about because it's the one that is less volatile and less subject to supply shocks, for instance. And on that note, nearly all the measures of underlying inflation that the RBA tracks, namely, trimmed mean inflation, inflation excluding volatile items, weighted median inflation, all of those measures, they all barely moved at all. In fact, all three of those measures actually still had a forehand along them in the first quarter. So it's almost certain that underlying inflation will be stronger than the RBA had anticipated in February. And so that's one of the big reasons that we think the bank will be inclined to raise rates because it has long been saying that its main priority is to bring inflation back to target within a reasonable timeframe. And given the upside surprise, it looks like that timeframe will likely be pushed out further down the line if it does not hike rates. And another reason that we think that there's a good case for the bank to hike rates is that the labor market is clearly also much tighter than it had predicted. So the labor market has quickly stopped loosening over the last five months in trend terms. The unemployment rate has stagnated at 3 .9%, which is only a touch higher than its 50 -year low of 3 .5%. So there's a strong case for the RBA to take those upside surprises seriously and to hand down another rate hike. Of course, it's possible that the RBA chooses not to hike rates, but we think it will at the very least reinstate its tightening bias, which it had done away with in its March meeting.

David Wilder

What about the flip side of that. I mean, you talk about the tiniest in the labour market, you talk about what's happening with underlying inflation, but even if the bank doesn't go ahead and hike rates at its next meeting, there is this question about the resilience of economic growth in Australia. I know you covered this March retail sales data that seemed to shock the market, seemed to suggest that households already struggling with policy settings as they are. Is data like that, do you think going to act as a break on any decision to hike rates at the coming meeting?

Abhijit Surya

So you're right that the retail sales data we got for March were quite weak and that they will be a concern for the bank, especially since there's long been voicing its apprehensions about weakness and household consumption in Australia. So what we've seen is the national accounts data show that private consumption has basically flatlined over the past few quarters. And if the retail sales data are anything to go by, that could continue to be the case. And if the RBA is keen on ensuring that household consumption doesn't go backwards, there is the possibility that the RBA chooses not to hike rates, especially given its concerns about the economy, but it is still likely to keep rates on hold for longer than most are anticipating. So potentially another rate hike coming at this meeting.

David Wilder

Talk about the path for rates. What does it signal about the timing of when the RBA will cut interest rates? And if they don't hike at this meeting, does that change anything about the timing of a cut?

Abhijit Surya

So in our view, this would be a case of one and done. We don't expect the RBA to hike any further. As some commentators have suggested, there are some forecasters who are predicting three rate hikes over the course of the year, although none, interestingly, at the main meeting. But even so, we think they won't lift rates above 4.6%. Basically, we view this rate hike as something of an insurance policy because a lot of the leading indicators we're tracking still suggest that there is disinflation in the pipeline. But given the recent upside surprises, the bank simply won't want to take that risk. And that being the case, we also think that the bank will cut rates a little later than we were saying previously at the start of the year.

You were inclined to believe that the bank would start cutting rates by August itself, but that's when the data told a different story. And now it seems that the bank will have to wait for longer before it can be confident that underlying inflation will return to target within a reasonable timeframe as it has long been aiming to do. Now you raise the question of whether there's a possibility that the bank will leave rates on hold and that may well be the case. Like I said, much will depend on the bank's reaction function.

And if it's overly concerned about damaging the economy and in particular inflicting more pain on households, it may leave rates on hold. But we still think that it will have to wait a while before it can be confident about cutting rates because inflation overseas has been sticky and Australia frequently takes its cues from the developments there. So it's probably still going to make sure that it doesn't cut prematurely and have to backtrack later. So that's why we think the first rate cut will come only in February of next year. That's a little later than what most other analysts think, at the end of this consensus for policy easing to begin in Q4 of this year itself.

David Wilder

But you just mentioned that the RBA's decision making hinges in part on what's happening overseas. Now there's been lots of debate about whether banks like the ECB, Bank of England, could cut rates before the Fed. We don't think there's much to stop them from doing so, but give us a sense of how the idea that the Fed starting to ease in September, as we're currently expecting, how that would affect RBA decision-making and talk a bit about the macro and market consequences of being a bank that's still on hold, still has this restrictive policy while others are moving towards easing policy.

Abhijit Surya

So you're absolutely right that the RBA does monitor developments overseas, but it nevertheless marches to the beat of its own drum. So for instance, when a lot of other central banks, including the RBNZ, the Fed had started hiking rates in late 2021 and early 2022. The RBA didn't join the bandwagon until much later. And even when the RBA did start hiking, it hiked less aggressively than most other central banks. So currently the policy rate in Australia is 4 .35%, whereas close to five or five and a half and a lot of other advanced economies.

So the RBA, while it likes to monitor what's happening overseas and see what lessons are applicable for its own policy making, it will still do what it sees as right in the Australian context. So if the RBA were to diverge from other central banks and hike while others are on the verge of cutting if they haven't started already, the main impact would probably be in currency markets because markets aren't pricing in a hike yet. So you would probably see the Aussie dollar make some gains against most other currencies and that in turn could at the margin help the disinflationary process because a stronger currency would mean that important inflation would be lower. Another rate hike could also see equities in Australia tumble a little bit but in any case the RBA will follow developments overseas but its policy actions won't be dictated by what happens there so it will ultimately do what it needs to do to get inflation under control.

David Wilder

That was Abhijit Surya from our ANZ team on the RBA decision this coming Tuesday. Whether the bank decides to hike or hold, our team will be responding within minutes of the decision with an instant reaction and following up with more in -depth analysis on what lies ahead for Australian inflation and rates and the aussie, so watch out for that. Finally this week, our commodities team held a drop -in online briefing with clients on potential risks to key prices.

They were talking oil, gold, industrial metals and much more besides. And here's a clip from that briefing, which I've edited for clarity. You'll hear Deputy Chief Global Economist Simon McAdam talking to commodities economists Bill Weatherburn and Kieran Tompkins. And the clip starts with Bill Weatherburn answering a client question about the impact on oil markets of the US election, specifically what Russia and Saudi Arabia could do in terms of production in the lead up to November's vote.

Bill Weatherburn

I think the thing about the US election, you know, sort of domestically and then within domestically considering just the production side of things, oil and gas production is at record highs. And regardless of who is in power at the end of this year or next year, for the next four years, it's very difficult to see how policy is really going to be the big factor in ramping up production of either oil or gas. What's going to matter is the price of oil or gas. And of course, the US is influenced by global oil and gas prices.

There's probably more scope for a new administration, say Trump administration, to alter US oil consumption because there's fairly ambitious vehicle efficiency standards that have been brought in. And if they were unwound or the subsidies for electric vehicles were unwound, you can see that oil demand would be a bit higher. That's probably not something that would actually be different in the first year, but you know, over a four-year period, if those sort of standards for emissions were scrapped, certainly US oil consumption would be a bit higher than we currently expect on the foreign side of, you know,

Does the election influence OPEC or OPEC plus policy? I don't think Russia has much in scope to withhold production. It's been very difficult for them to be compliant with the existing OPEC plus production cuts. I think they're trying to maximize revenue in a sort of constrained space so that they may say that they'll withhold production, but I doubt they'd actually do it or cut exports back. Saudi Arabia is a harder case. I think we are expecting Russia or OPEC Plus as a whole to raise output when they next meet in June, gradually not unwinding all of the cuts that they've made, but some of, you know, partially some of them. I wouldn't be surprised if this turns out that Saudi keeps its voluntary cuts in place, but the rest of the wider group increases in some supply. It's just many members of OPEC Plus are very eager to exploit their existing reserves while oil demand is still rising. And, you know, our Middle East team is just sending a message explaining that the UAE has actually increased its productive capacity already. So it is clearly some signs other members of OPEC plus are very eager to expand out. Yeah, they've got to make the most of it while that window of opportunity is still there, isn't it? Well, before we get to peak oil demand.

Simon MacAdam

Right. OK, Kieran, we've had a couple of questions actually on copper. Essentially can be boiled down to, has the copper rally been overplayed in the short term? And related to that, are there any senses of restructural shortages over the next couple of years might affect prices going forwards?

Kieran Thompkins

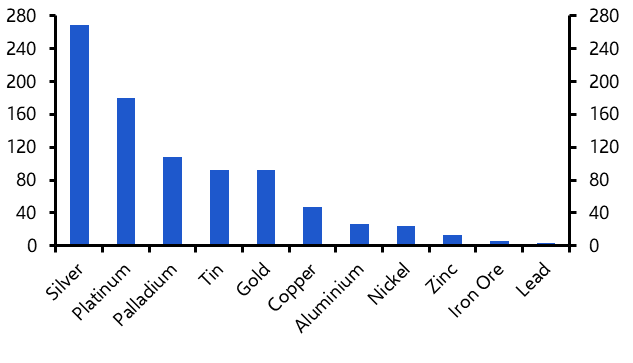

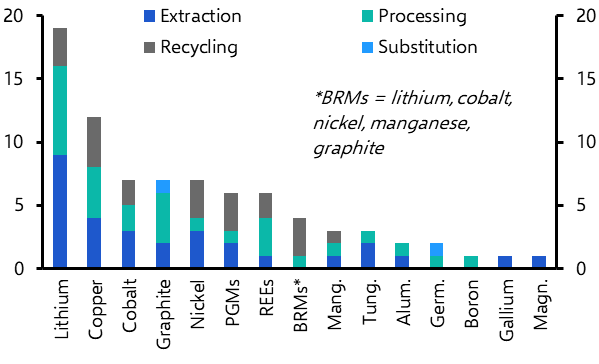

Yeah, so taking that first one, the rally in copper prices is, well, that rally hasn't just been solely to copper prices. We've seen it across all base metals. We've seen prices between 10 and 35 % up year to date. And I think essentially our view is that yes, that rally kind of does seem to be overplayed. Net long futures positions look incredibly stretched now for copper. Those net long positions by speculative investors are comfortably larger than the period of China reopening at the beginning of last year, and also much larger than say during the reemergence of the global economy from COVID in late 2020 that saw copper prices break out immeasurably. And our sense is that right now, I don't think the conditions really warrant that kind of optimism, even though we have seen emergence of some supply constraints within the copper market. We think the rally is probably a little bit overdone. So our forecast is for the copper prices to edge a bit lower by the end of this year. Our forecast is $9,250 per tonne compared to a latest price now of around $9,800.

To take your second question of around structural shortages developing, I think it's interesting to raise that or take in a much closer look at some of the structural changes underway in metals markets. And that's beginning with the, we will be forecasting green transition demand and we should be publishing a focus on that next week. But this isn't the only structural force that is underway for metals demand. Our China team actually pointed out in a great focus from earlier this year, which was laying out our view of the property sector in China. That construction activity in China's property sector has barely yet to fall despite some of the very doom and gloom headlines we've seen around China's property sector. Instead, construction is being propped up by things like developers continuing to work on backlogs of projects and infrastructure spending. So the bigger downturn is yet to come in China's property sector, which will be a very large drag on metals demand as well. So in the coming weeks, we do hope to look at the net impact of those two structural forces in much more detail. But I think taking a bit of a stab at it, if structural shortages were to emerge, our eyes would definitely be on copper for that. It's central to the green transition with its use in pretty much most areas. It's used in EVs, renewables. It'll be needed for expansion of the electricity grid. And that coupled with underinvestment in new supply. Meanwhile, existing mine supply is already struggling as mines age or all grades deteriorate and issues like resource nationalism posing key threats to new investment decisions. So yeah, I think if there was one metal to keep an eye out on, it would definitely be copper with that respect.

David Wilder

That was Kieran Tomkins on copper prices. There's a lot more in the full recording, which I'll post on the podcast page, including what's been driving this year's hefty gold price rally and what a shutdown of the Straits of Hormuz would do to oil prices.

As Kieran mentioned our focus reports, these are in -depth analysis pieces. I'll link to the China one that he mentioned, but also get him on the podcast to talk about that focus on the green transition and metals demand in the coming weeks. But that's it for this episode. We'll be back next week with more on inflation, central banks, the dollar, global imbalances and much more besides.

Until then, goodbye.