It’s become almost too easy to knock Davos in a post-pandemic, fracturing world. The World Economic Forum may not be part of the solution to the world’s problems that its marketing team would have us believe, but it at least gives a fairly good steer of the issues that are dominating debate in government and boardrooms worldwide.

Perhaps the most popular talking point at this year’s gathering in the Alps was the disruptive consequences of the AI revolution, a theme which generated its usual flurry of headlines, ranging from the broadly optimistic to the borderline apocalyptic. Unsurprisingly, at least some of the coverage was highly misleading.

Let’s start with the optimistic takes which, at a macro level, we think are mostly justified. Nearly 60% of global chief executives believe generative AI will improve the quality of their products or services within the next 12 months, according to a survey conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers ahead of this year’s Davos gathering. Moreover, almost half (46%) said they believe that AI will also boost their firm’s profits over the timeframe.

Of course, this says nothing about the scale of the improvements to either product quality or profitability. But the fact that such a large number of CEOs believe that generative AI will deliver improvements in such a short space of time is surely good news for those (like us) that believe it has the potential to transform the economic outlook.

Our work on AI’s macro and market consequences last year argued that the technology could boost productivity growth by up to 1.5%-pts a year in the decade following its widespread adoption. Based on past technology trends, we assumed that widespread adoption would not happen until the back-end of this decade, meaning that the boost to growth would come mainly in the 2030s. But these estimates are more art than science and it’s possible that the technology is adopted more quickly than we had anticipated. If so, it follows that the economic benefits will arrive sooner.

AI-pocalyse now?

The more apocalyptic headlines around AI continue to relate mostly to its labour market impact. The same survey reporting optimism among CEOs about what AI will mean for their bottom lines also reported that one-quarter of business leaders believe it will lead to a reduction in headcount of at least 5% at their firms over the next year. It’s a result that dovetails with a recent IMF report warning that around 40% of workers are exposed to AI’s impact. While this has fuelled long-standing concerns about mass technological unemployment, these are misplaced fears based on muddled reasoning.

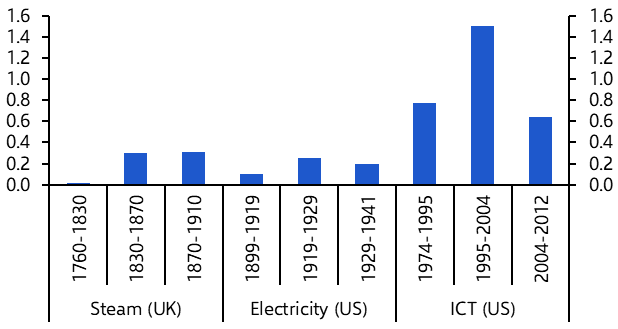

AI will affect such a large share of the workforce because it is what economists call a ‘General Purpose Technology’ or GPT. These are technologies with a wide range of applications throughout an economy. The three classic examples are steam power, electricity and the Internet, all of which led to a fundamental restructuring of how firms across economies operate. And it was precisely because they had such a wide range of applications that they delivered a broad increase in productivity growth (albeit spread over different time frames). (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Contributions to Labour Productivity Growth (% Points Per Annum |

|

|

|

Sources: Crafts (2020), Capital Economics |

However, the fact that large numbers of workers will be affected by AI – and that some will lose their jobs as a result – does not necessarily mean a sharp rise in unemployment is in the offing. If nothing else, while some jobs will be lost, new ones will be created. This is what happens when new technologies are deployed in market economies. A 2020 study by MIT’s David Autor found that 60% of occupations in the US today did not exist in 1940.

Moreover, what matters for unemployment is the effect on overall labour demand and supply. If we are right in believing that the AI revolution will deliver large productivity benefits then it should lead to an increase in real incomes and spending, therefore creating additional demand for workers.

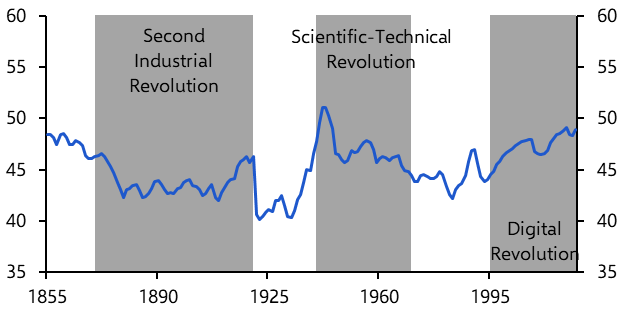

The lesson throughout history is that, while technological advances have caused some workers to lose their jobs, the positive consequences for labour demand in aggregate have won out in the long run. Chart 2 shows employment’s share of the total UK population has fluctuated since the mid-1800s, but there’s no evidence to suggest that technological progress has fundamentally damaged employment. Put differently, AI is likely to be an enormously disruptive force that reshapes how firms operate and displaces some workers – but it is wrong to conflate this disruption with a rise in overall joblessness.

|

Chart 2: UK Employment (% Share of Total Population) |

|

|

|

Sources: Bank of England, Capital Economics |

Riding the market wave

For investors, the key will be to identify the market implications of what is a highly uncertain but, on balance, positive macro story.

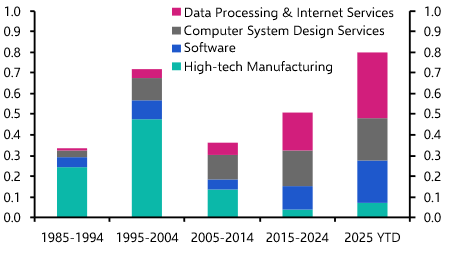

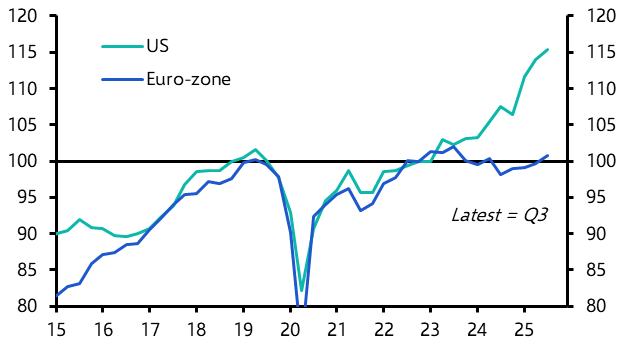

John Higgins, our Chief Markets Economist, recently reiterated our bull case for equities, showing how AI’s potential to deliver large productivity improvements means corporate earnings should also get a significant boost. In the first instance, this will be helped by the fact that the gains from AI are likely to flow to capital rather than to labour. But his report also showed how investors have historically sought to capture the perceived economic benefits of new technologies ahead of those technologies actually diffusing through the economy. Given the inherent uncertainty around exactly how these technologies will develop – and the fact that they tend to get hyped up – this also means new technologies are prone to bubbles.

Crucially, the report shows how, while AI has undoubtedly been an important driver of equity markets over the past year, most metrics indicate that, if a bubble is to inflate around AI, we are likely to be only in its early stages.

This is a macro – and a markets – story that has a lot further to run.

In case you missed it:

- While US equities are set to continue outperforming amid AI hype, their global peers will still do fairly well, says Markets Economist Hubert de Barochez.

- Not only are the challenges of the “last mile” of disinflation in the US being overstated, but the data show a growing risk of below-target inflation, warns Chief US Economist Paul Ashworth.

- Despite more geopolitical tension in the Middle East, natural gas prices actually fell last week. And they’re likely to fall further between now and year-end, says Commodities Economist Bill Weatherburn.