It’s Political Economy 101 that if the cost of household staples rises for long enough then governments will reach for price controls. This is exactly what is starting to happen across Europe in response to the sharp rise in food prices over the past year.

Actual price controls have so far been contained to a handful of smaller EU states, such as Hungary and Croatia. But France’s government has agreed a deal with major food retailers to cut the price of a wide range of foodstuffs to the “lowest possible level” – albeit with significant discretion for retailers over how to implement this. And reports in the weekend press suggested that the UK government is considering a similar move if public jawboning of retailers and manufacturers to lower prices – itself a form of soft control – yields no results.

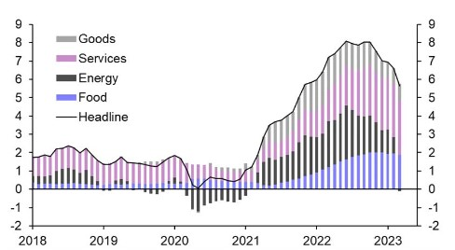

Viewed in purely political terms, it is clear what is motivating governments. Consumers – voters – are acutely sensitive to the price of food because they buy it so much and so often. Food inflation is currently 13.6% y/y in the euro-zone, and data released last week showed it running at 19.3% y/y in the UK. Food is now making a greater contribution to headline inflation in advanced economies than energy. Little wonder that accusations of “greedflation” on the part of retailers and producers are flying thick and fast.

|

Chart 1: Contributions to Headline CPI Inflation in Advanced Economies (%-pts) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

While price controls used to be viewed as a form of heresy within economist circles, opinions are starting to shift. Respected German economist Isabella Weber has been a strong proponent of controls on energy prices and her views are entering the mainstream. Indeed, most economists generally accept that the introduction of energy price caps and/or subsidies across Europe over the past year was the least worst policy option given the circumstances.

However, while there is clearly a legitimate role for price controls in situations where economies are experiencing huge supply shocks – notably in times of war – they are, by design, distortionary and should only be used in extreme circumstances. The current food price shock does not warrant such an intervention.

First, despite claims to the contrary, there is no evidence that double-digit food inflation is the result of price gouging. Instead, the surge in food inflation reflects an increase in global agricultural prices over the past 18 months, caused by poor harvests and disruptions to wheat supply from Ukraine, combined with an increase in energy prices that has driven up the cost of food production. As a result, the S&P Global Agricultural Price Index increased by over 30% in 2022 compared to 2021. Put simply, the price of food has gone up because it’s much more expensive to produce. The margins of both food retailers and producers have remained stable. (See Chart 2 & 3.)

|

Chart 2: Net margins of food retailers |

Chart 3: Net margins of food manufacturers |

|

|

|

|

Sources: Bloomberg, Capital Economics |

Second, the price mechanism is a crucially important vehicle for conveying information and influencing behaviour. By discouraging new supply and encouraging additional demand, the imposition of price controls will only make the current food inflation shock worse.

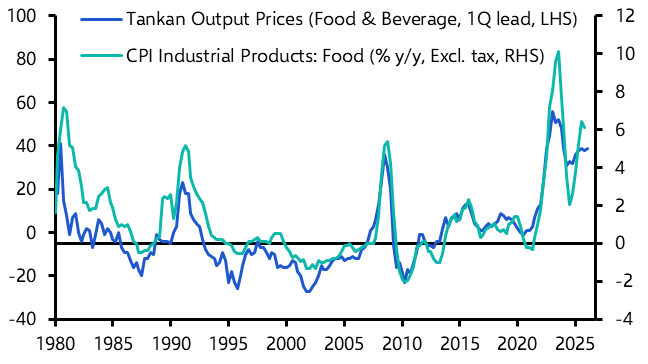

Finally, food inflation is likely to come down anyway without the imposition of price controls. The usual lagged relationship between changes in global agricultural prices and food inflation suggests that the latter should already have fallen sharply across developed economies. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 4: GSCI Ags./Livestock & %-pt Contribution of Food/Bevs. |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

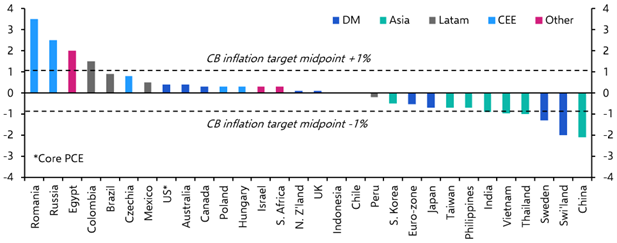

The fact that it hasn’t is probably due to the continued pass through of higher energy prices to production costs, as well as strong wage growth, which has contributed to a rise in catering services inflation. However, as we set out in a recent note, a combination of lower agricultural and energy prices should start to pull down food inflation over the coming months. As a result, the contribution of food to headline inflation in advanced economies should fall from around 1.5%-pts now to just 0.5%-pts by the end of the year. (See Chart 5.) In other words, falling food inflation could shave around 1%-pts off headline inflation by end-2023.

|

Chart 5: Contributions of Food to Average Advanced |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

As well as a political headache for governments and a monetary pain for central banks, rising food prices create real hardship at the lower end of the income distribution, where a larger share of household budgets is typically spent on food. But the solution to this problem is to keep inflation expectations anchored and to deal with distributional challenges through fiscal transfers.

Price controls may be politically expedient, but they are not the answer to the food price shock.

In case you missed it:

- Although Joe Biden and Kevin McCarthy finally reached an agreement, the debt ceiling saga isn’t over as the deal still needs to pass Congress.

- The latest reading of our China Activity Proxy, a proprietary measure of Chinese economic activity, suggested the post-zero-COVID recovery progressed at the start of Q2, albeit with some loss of momentum.

- Our latest Climate Economics report explored the decarbonisation challenges of the aviation sector. David Oxley, the head of our Climate Economics coverage, is also on this week’s podcast, discussing how rising temperatures interact with our long-term economic forecasts.