The Weekly Briefing:

How did a UK recession just get more likely?

A Capital Economics podcast

26th May, 2023

Neil Shearing says the UK’s April CPI report was a “horrorshow”. The Capital Economics Group Chief Economist tells David Wilder why sticky inflation readings make recession more likely – despite the popular view that a downturn can be avoided – while previewing May inflation data for the euro-zone and the US non-farm payrolls report.

Plus, the reports suggest a deal is near, but what if Democrats and Republicans fail to agree in time and the US actually defaults? Hear an exclusive clip from our client briefing about the macro and market impact if the unthinkable became a reality.

Also, most studies tend to understate the impact that a bigger-than-expected rise in global temperatures would have on economic activity. David Oxley, the head of our Climate Economics service, has tried to put that right with new analysis. Here he talks through some of the global and country-level impacts.

Transcript

David Wilder

It's Friday 26th May and this is your Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. I'm David Wilder. Coming up, we have an exclusive clip from our debt ceiling client briefing, and we'll be hearing why most forecasts understate the impact of rising temperatures on the global economy. But for now I'm joined by Group Chief Economist Neil shearing. Hi, Neil.

Neil Shearing

Hi David.

David Wilder

Let's start with UK CPI. We warned of the risk of an upside surprise ahead of the Wednesday release and that's certainly what we got. How has that April report changed the narrative about the economic outlook, about where inflation is going and about what the Bank of England is going to do for the UK economy?

Neil Shearing

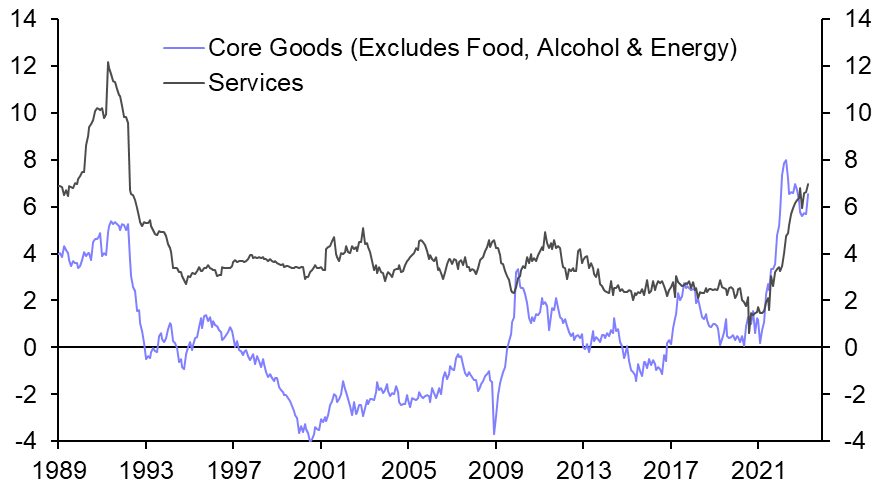

Yes, a bit of a horrorshow on UK inflation over the past week. It sounds odd to say that, given that headline inflation fell from 10.1% in March to 8.7%, in April, but of course, it was the rising core inflation which spooked the gilt markets – that's now at a 31-year high believe it or not – so more evidence that we've gone from this phase where inflation has been driven primarily by food and energy and goods inflation related to the pandemic and is now coming through in the form of services inflation and linked to high wage rates. So wage settlements in the UK stubbornly high at about 6%. That's clearly inconsistent with a 2% inflation target when you have productivity growth that's gone nowhere in the UK for several years. So, big inflation challenge for the Bank of England. What does that mean? I think it means two things: one is that the bank has more work to do. So we've raised our forecast for interest rates. We now expect UK rates to peak at five and a quarter percent later this year, starting with another 25 basis point increase at June's MPC meeting. I think that actually there's a good case for a 50 basis point hike in June if the May inflation data surprise on the upside too – that will be released before the MPC meeting. And the second thing I think it means is that the chances of a UK recession at some point over the next year or so have actually increased. Now, the activity data over the past couple of weeks have actually been quite resilient, including an upside surprise in the April retail sales data over the past week too, but with the Bank of England having to push back harder against inflation pressures and bear down more on demand, I think that eventually will start to feed into consumer spending and output in the economy and I suspect that recession is now looking a bit more likely.

David Wilder

So recession likely in the UK. What about the eurozone, because we've got eurozone inflation, the preliminary May reading coming Thursday. That will be coming off the back of that German GDP data that confirm the economy went into recession at the start of the year. Is this the moment our Europe team has been warning of for some time now where the ECB is raising rates in the face of economic contraction in the euro-zone?

Neil Shearing

I think it is. I mean, we’re there already. The German economy is contracting now for two consecutive quarters – that fulfils the definition of a technical recession. But actually, I think what’s more likely to happen over the second half of this year and into 2024 is slightly different, both in the euro-zone in the UK. The first part of economic weakness over the past six to nine months has really been about the huge squeeze in real incomes and the way that's affected household spending because of the large rise in energy prices and food prices and the inflation shock that’s rippled through Europe. The next phase of economic weakness is going to be in response to higher borrowing costs. So higher interest rates. And I think that's the shoe that's yet to drop across Europe, including in the UK. Now, when it comes to the eurozone inflation data to be published over the next week, I suspect the headline rate is going to fall – it was 7%. In April, we're going to be getting May’s data. That's going to come down we think to just over 6%, again, driven by food and energy, but it's the core number that matters. And that probably we think didn't change much from the 5.6% rate in April. I say probably didn't change much. There's scope for a bit of a downside surprise because of Germany introducing another cheap public transport ticket in the month of May that might push down core inflation a bit temporarily. But it's still stubbornly high, I think, is the main message and uncomfortably high for the ECB. So yes, the ECB with more work to do – a bit like the Bank of England. And again, as we've discussed on this podcast, rates, in our view, going all the way to 3.75% in the cycle later this year.

David Wilder

I noticed there's been a spike in Google searches for the term “stagflation” over the past week, and apparently wide-leg trousers are the season's hot fashion item – but let's call them flares, shall we? Are these signs that we're going back to the 1970s?

Neil Shearing

Could be – maybe disco dancing is back in as well! Every time we get weak economic data alongside high inflation clearly that evokes comparisons with the 1970s. There’s still, I think, substantial differences with that period. One is with the institutional structures and the way that the labour market operates – very different now compared to the 1970s. The second big difference is the response of central banks. Actually, central banks have raised interest rates very aggressively in the face of higher inflation this time around whereas in the 1970s, Arthur Burns and co were suggesting that there’s not much that central banks could do about trying to fight inflation. So that's one reason why expectations have remained more anchored this time around. And that's important when we think about where inflation ultimately settles over the medium term and how much more work central banks have to do. So I think they've got more work to do. I think they're going to be – certainly in Europe – slower to cut. That will be next year, 2024, when they'll consider cutting rates, probably in the back-end of 2024. But some optimism, some hope that inflation won't get embedded in the same way that it did in 1970s still, I think.

David Wilder

One economy we haven't mentioned yet is the US. It's been showing greater resilience of late, for the coming week non-farm payrolls is the big release. Can you talk through our expectations and how they fit with this prevailing and fairly benign disinflationary story?

Neil Shearing

Yes, clearly, a lot of attention is still on the debt ceiling negotiations and how they're playing out. By the time this podcast is released, we may be in a different position as regards that. But payrolls is the most important data release over the next week. And it's always a strange one this – it moves markets, the markets focus on it, but it's an incredibly volatile series and one that’s prone to revision. So last month, in April, we had a surprisingly strong number 253,000 jobs added in the month, which bucked the downward trend. But if you look at the three-month average, the trend down is pretty clear. We've gone for a 200,000 increase in payrolls in May. But the most important thing to keep an eye on I think, is what's happening to average hourly earnings. Now, this isn't the best measure of wage growth in the economy – we prefer the ECI index – but average hourly earnings has been trending down and if you look at the private quits rate, which is, in our view, the best measure of labour market slack in the US, that's consistent with another slowdown in average hourly earnings rate – probably 4.2% year on year in May. Also the quits rate suggesting will fall a bit further in future months, perhaps down to 4% year on year by the start of Q3. So keep an eye on the payrolls numbers and the jobs added – that's clearly going to grab the attention of the markets but it's the the earnings numbers that really matter for the Fed, I think.

David Wilder

That was Neil shearing on non-farm payrolls, UK recession and euro-zone inflation. Our Europe team will be briefing clients on Thursday, shortly after the release of the May inflation numbers, so watch out for that. I'll also link to Neil and Paul Dale's note on what’s needed to bring down UK inflation. Coming up, global warming and the global economy. But first, as Neil mentioned, another big market risk event for the coming week is what's happening with the US debt ceiling. Reports say Republicans and Democrats are nearing a deal. Our expectation is that one will be agreed but nothing's guaranteed until the deal gets done. I'll post our latest analysis on what's happening with the debt ceiling in the show notes. But to understand what's at stake, here's an exclusive clip from a client briefing we held a few weeks ago that walks through what could happen if the unthinkable became reality. And the US actually defaulted. Discussion was led by Paul Ashworth, our Chief US Economist, who's talking in this clip with Jonas Goltermann, our Deputy Chief Markets Economist and Deputy Chief US Economist, Andrew Hunter. You'll have to forgive some occasional shonky sound in this clip, which begins with Jonas explaining how markets could take the news of a default

Jonas Goltermann

There's really no way to know what’ll happen, except that it would probably be quite bad. I think you can sort of divide it into two kinds of effects, right? One is this sort of plumbing issue you would have immediately with people expecting money and not receiving it. And then people they owe money to not receiving it and the whole chain sort of playing out, in the first instance across the money market, but potentially sort of affecting the wider economy and turning into a macro economic downturn. But I think in terms of what the market reaction would be, you know, if we're getting really close to that date, it would be equities down, Treasury yields, ironically, would probably go down as well because, the fear is that this will trigger the recession that everyone's talking about, and everyone’s worrying about. If you go back and look at previous episodes, the time when we got closest to the X-date and actually triggering that outcome was in 2011. And then you saw the stock market fall – I think it fell more than 10% in a few days in early August. It continued falling even after they had passed the bill. At that point Treasury yields fell quite sharply as well. Now, the debt ceiling wasn't the only thing going on back then – it was also one of the peaks in the euro-zone crisis. So, that certainly played a part as well. The market was worried not only about the US, but how the debt ceiling was interacting with all the problems that that were going on then in the euro-zone at the same time. So maybe that's an exaggeration. On the other hand, it fell that much without actually going past the X-date. So, you know, if you're do you might get a bigger reaction.

Paul Ashworth

I mean, it really comes down to reactions that you see also from ratings agencies and regulators. So if ratings agency just take one notch off the AAA rating, that's not an issue. If, for some reason, they were to make US debt no longer investment grade, for instance, and downgrade it that much, then I think at that stage all hell would break loose because then it would come down to the regulators, because of course, there's institutions all over the world holding US Treasury securities as a form of risk-free capital, but which suddenly wouldn't be risk-free and wouldn't qualify and cause all sorts of chaos in money market funds that would be breaking the buck. That really would be a much more serious scenario than the Treasury misses a coupon payment, the ratings agencies respond conservatively, regulators say “don't worry – still this is still risk-free capital”. And it also depends on what the Federal Reserve does, because if the Federal Reserve is still accepting Treasury securities as perfectly good collateral, that means people can always liquidate out of their positions using either the repo facility, the discount window or the new bank term funding programme. So it's all depends on what everybody else does. And I think everybody has an incentive to treat it as conservatively as possible because, as we keep coming back to, this is a technical default in that sense of the word. And there's no reason with the ability to print its own currency, that the US government can't continue to service debts, however, much it issues. That may lead to inflation, it may lead to weakness in the currency, but it's certainly not going to lead, in the near term, to a debt default. So Andrew, what do we think about the impact on the economy? One from, I guess, a less serious scenario where we just miss temporarily some social security payments, maybe some Medicaid, Medicare payments to this most severe scenario where there’s an actual outright debt default.

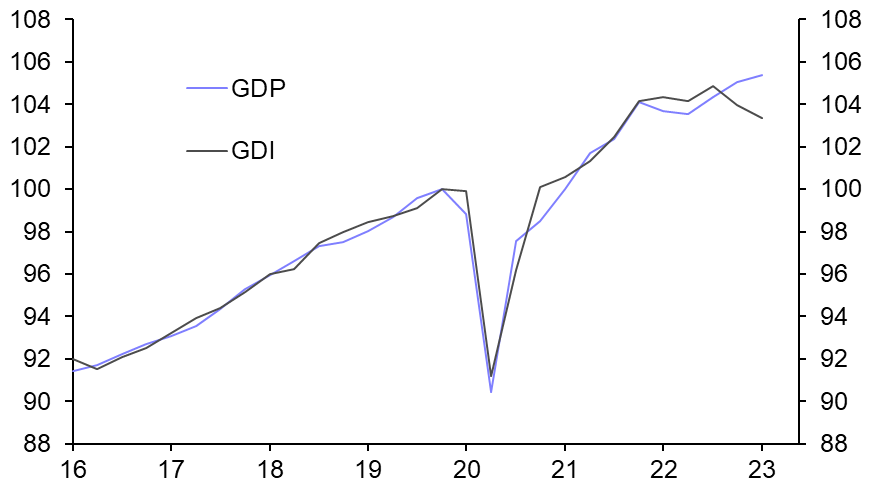

Andrew Hunter

So I guess it's worth noting, even if we don't get a default, I think it’s possible that, you know, negotiations running right up until the last minute, you know, would obviously generate significant fears that the deadly might be missed. I think that in itself could potentially exert some drag on the economy if it hits business, consumer confidence, things like that, it's certainly by all accounts proving already to be a pretty unwelcome distraction for banks and firms in the financial sector who are obviously having to do far more contingency planning around a potential default. But I guess if we do breach that deadline without a deal, I suppose the main thing worth acknowledging is that it would be uncharted territory. No one can predict exactly how significant the damage would be. But I think it certainly could be severe. I suppose one way of quantifying the whole thing, obviously, it would depend how long this hypothetical default lasted. But ultimately, you know, in the scenario where the Treasury runs out of funds, no more debt can be issued, only about 75% of government spending is covered by tax revenues right now. So you'd be looking hypothetically at about a quarter of government spending ultimately being stopped, even if only for a temporary period. So I guess that gives you some sense of perhaps how severe it could be if there was any kind of long lasting default.

David Wilder

That was Paul Ashworth, Jonas Goltermann and Andrew Hunter on what a US debt default would look like. You can watch a recording of the full briefing on our website. But if you're a subscriber to CE Advance, our premium platform, you get access to all our live events. Finally, this week, David Oxley, who heads our Climate Economic services has just published new analysis about what rising temperatures could mean for the global economy. It's important because existing studies tend to underplay just how much economic activity is going to be affected by climate change. I spoke to David about the work earlier in the week and I started by asking what's in store for the global economy if temperatures rise more than expected.

David Oxley

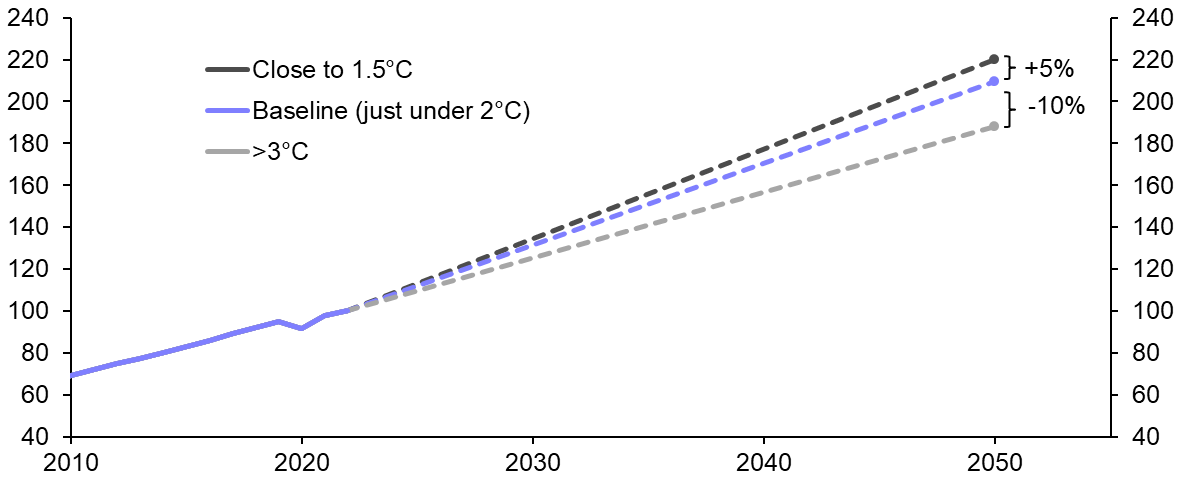

So we estimate that global GDP will be about 10% lower by 2050 if the world were to go down a path in which the global average temperature rose by more than 3 degrees from its pre-industrial average. This is a bigger impact than many studies in the literature have come up with. However, it's worth noting that it is still consistent with global GDP nearly doubling in size between now and the middle of the century. This is largely because developed economies would be affected the least by this degree of warming. And even in the places where a warmer world would have a much bigger impact on GDP, particularly in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia, the physical effects of climate change on economic activity would really manifest themselves as a headwind to catch-up growth in these countries rather than something that puts economic development in reverse.

David Wilder

10% sounds like quite a significant hit – doesn't that imply climate change is going to cause a fair amount of damage to the global economy?

David Oxley

So yeah, the level will be 10% lower but the baseline view is that global GDP will more than double over that period. So everything's relative and that's one of the big things you have to take into account when you look at economic impact studies. I think it's careful to bear in mind what this exercise can tell us. GDP is arguably not a very good measure for capturing all of the impacts of climate change. So it's very much a narrow measure and it's not suited to plugging it into a cost/benefit analysis of whether we invest in mitigating this outcome or not, or actually whether we just invest in adapting to a changing world.

David Wilder

Can you talk through how something like this gets estimated? What's wrong with the current studies?

David Oxley

Well studies looking at the potential economic impacts of different climate outcomes rely on so-called “damage functions”, which translate different climate outcomes in the future to economic performance. You might look at the potential impact of hotter temperatures on, for example, crop yields in the agricultural sector, and also agricultural productivity from people physically not being able to stay outside in the heat and work as hard as they could do in a hotter world than they can currently. The problem with these damage functions is that they are well known to be the so-called weak link in any estimate in translating any climate outcome to economic performance. So, this is partly because any estimate is only as good is what you're actually trying to capture. There are all sorts of individual channels in which hotter temperatures can impact on economic performance. And different studies try to account for as many of these as possible but there's always scope for things to be missed off, particularly the highly uncertain impacts on migration flows in the future that could occur in a warmer world. And the other key problem with so-called damage functions is that they are invariably derived from econometric estimates which, by definition, assume that the past is going to be a guide for the future. This might be the case in which if the temperature was going to increase slightly over what we've seen in the past, but there is lots of potential for tipping points and non-linearities in the relationship between climate variables and economic variables. So, yeah, so just assuming that the past is going to be a guide for the future is arguably pretty questionable and it throws a huge amount of uncertainty into the mix.

David Wilder

Okay, so let's drill down a bit from the global view, because your report makes clear that country-level impacts are going to be far more pronounced than anything on a global basis. I know you've touched on some of those. But can you talk through the country level impacts that really stood out to you while you're doing this analysis?

David Oxley

Yes, as you as you say, the global picture masks significant variation at a country level. In keeping with a lot of the findings of most studies out there, one key thing that stands out is that developed economies are least likely to be affected by rising temperatures. This is partly due to compositional factors in that the industries and sectors that are most likely to be negatively impacted by higher temperatures – agriculture, tourism – are typically smaller parts of economies in the developed world than they are in the emerging world. So the numbers we've produced typically have GDP falling by less than 5% by the middle of this century relative to our baseline in the developed world in a situation in which the world warms by more than 3 degrees from its pre-industrial average. The flip side of this is that, in general, we see much bigger impacts in emerging market economies. So, when you run the numbers, the biggest downside risks for activity from a warming world tend to be in Southeast Asia, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, could all plausibly see GDP 25-30% lower than our baseline by the middle of the century if the world was going to warm up. And India's another economy that really stands out with GDP estimated to be around about 20% lower than it otherwise would be if the world was likely to warm up.

David Wilder

Our Long Run Economic Outlook published earlier this year has new rankings on where we see the world economies between now and by 2050. It might help just to talk through how those rankings will change as a result of a higher-than-expected rise in global temperatures.

David Oxley

Yes, well, the key point is that if we focus on the top 10 largest economies in 2050, in our baseline scenario and what we think would happen in a warmer scenario, the same 10 countries make up the list in both cases. However, the rankings do change slightly. As I mentioned, Indonesia is probably the country that stands out the most, Indonesia would still be expected to rise into the ranks of the top 10 largest economies by 2050, from number 16 at present. However, in a situation in which the world warmed up, we think it would top out at the eighth largest economy, slightly below France, as opposed to our baseline view in which it overtakes France, Japan and the UK to become the fifth largest economy by 2050. India is another country whose GDP could be significantly affected in a warmer world. This wouldn't change our view that it would still rise to the third largest economy in the world. However, its lead over fourth place Germany would be cut. So instead of being around four times larger than the German economy by 2050, it would be around about three times larger. So it wouldn't change the ranking but overall the size of the economy would be considerably smaller.

David Wilder

So this threat of a higher-than-expected rise in temperatures, developed markets less affected certainly than economies in the emerging world. But for economies in the emerging world, this isn't going to reverse their development process so much as weigh on it, drag on their potential.

David Oxley

Yes, exactly. We still think there is or there is significant potential for catch-up growth in many of these economies. But this will be somewhat harder in a warmer world, which reflects the fact that GDP will just won't be able to grow. The catch up process won't be as rapid as we expect in our baseline.

David Wilder

That was David Oxley on the economic impact of a bigger than expected rise in temperatures. That's it for this week. Look out for our coverage of inflation, climate and the debt ceiling on our website, capitaleconomics.com. And for complete access, including powerful data and charting tools and those invites to all our live events, do check out CE Advance, our premium platform. Don't forget to subscribe to this podcast via Spotify, Apple or wherever you listen. But until next time, goodbye.