How to fix the global economy? I explained last week why global trade imbalances matter and outlined a framework for thinking about a ‘grand bargain’ to reform the global trade system.

The core challenge is reducing trade imbalances while keeping the economies involved at full employment. That means narrowing the US current account deficit and reducing surpluses in countries like Germany and, especially, China without stifling aggregate demand in any of them.

There’s no shortage of proposed solutions, including a widely circulated strategy by Stephen Miran, now head of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers. But the ideas that are currently getting the most attention fail to address the core challenge – and at best won’t make much difference.

Getting to the heart of the problem

As I noted last week, the big misalignment within the global economy lies in the savings and investment behaviour of major economies, particularly the US and China. Put simply, the US saves “too little” and spends “too much” and China saves too much and spends too little. The best way to redress this would be through coordinated action to rebalance expenditure: squeezing domestic demand in the US via fiscal retrenchment, while reflating domestic demand in China through policies that bolster consumer spending. This should reduce trade imbalances without dampening aggregate demand in either economy (since stronger demand in China would, all other things being equal, suck in exports from the US).

But achieving this will be difficult. China’s leadership has spent years paying lip service to encouraging consumer spending but this so far hasn’t translated into meaningful policy action. At the same time, a significant fiscal consolidation in the US seems unlikely, particularly if the Trump administration is serious about pushing through tax cuts.

Accordingly, a coordinated global rebalancing may make economic sense, but the political reality is far more challenging. The deepening rivalry between the US and China only complicates matters; while both nations would need to embrace change, neither would want to appear to concede ground. (For the same reason, trying to force expenditure rebalancing through formal mechanisms, such as a modern-day equivalent of John Maynard Keynes’ “bancor” plan, would also likely founder.)

Tariffs are a blunt tool

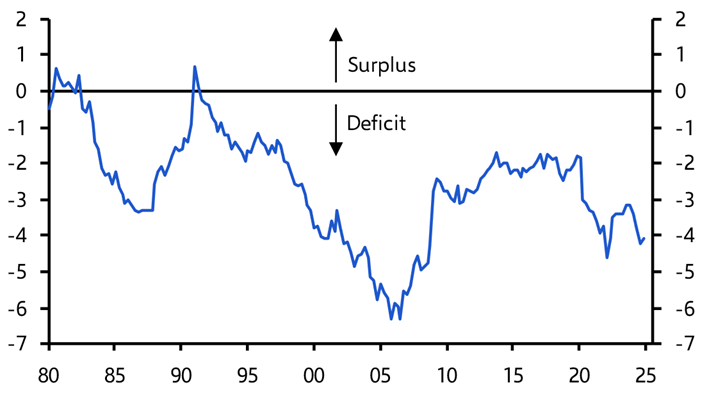

If expenditure rebalancing is off the table, deficit countries might turn to “expenditure switching” policies to shift US demand from imports to domestic goods, and foreign demand toward US exports. Tariffs aim to do this and are central to many US trade reform plans, including Miran’s. But history shows they are a blunt tool with limited impact. Tariffs imposed during Trump’s first term – and maintained and extended under Joe Biden – didn’t stop the US current account deficit from widening. (See chart.)

|

US Current Account (% of GDP) |

|

|

|

|

At best, a modest increase in tariffs could generate revenue to finance an extension of Trump’s 2018 tax cuts. At worst, significantly ratcheting up tariffs could do serious damage to the global trading system and lead to much weaker growth in the US and elsewhere. But as a tool to rebalance global trade, higher tariffs are unlikely to be very effective. If nothing else, in a world of floating exchange rates, the effects of higher tariffs tend to be offset by currency adjustments. This raises the question of whether imbalances could be tackled through a combination of tariffs and measures to realign exchange rates.

Currency realignment

A push to realign exchange rates would aim to weaken deficit-country currencies (like the dollar and possibly sterling) and strengthen those of surplus countries (notably the renminbi, yen, and euro). This would be more effective than tariffs, which only affect imports, as it would impact trade going in both directions.

The mooted plan to address imbalances between the US and its key trading partners has been dubbed a ‘Mar-a-Lago Accord’ in conscious echo of the Plaza Accord, the 1985 agreement between the US, Japan, West Germany, the UK and France to weaken the dollar and reduce trade deficits.

Similarly, the new accord would require selling dollars, which could be done by surplus countries offloading their dollar assets. While this would push up US borrowing costs in financial markets, Miran proposes the US counteract this by pressuring its allies to swap their remaining holdings of US government bonds for century Treasury bonds in exchange for continuing US military support.

The intention would be to insulate US public finances from a rise in borrowing costs, but there are several problems with this idea, not least that a) most dollar assets held by US allies lie in the private sector and b) China has large official holdings of US Treasuries and clearly falls outside of the US security umbrella.

The more fundamental challenge is that most countries will resist efforts to strengthen their currencies. A stronger renminbi would exacerbate China’s problems with weak growth and rising deflationary pressure while Japan wouldn’t want any sudden yen appreciation just as it finally appears to be exiting three decades of deflation.

This raises the prospect of a unilateral attempt to weaken the dollar. In theory, the US government could print dollars and sell them to weaken the currency. In practice, the administration would need to get the Fed on board, and that would require a commitment to fiscal retrenchment to counteract any inflationary effects of a weaker dollar. We have already seen that this is unlikely. Alternatively, the administration could create a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) to invest in foreign assets and try to weaken the dollar but this would need to be large-scale to have a lasting impact and setting it up would take years.

The tail wagging the dog

One overarching problem with any push to substantially weaken the dollar is that, while the currency looks a bit strong, it is difficult to make the case that it is significantly overvalued. (We think it may be about 10% overvalued on a real trade-weighted basis.) Past efforts to realign exchange rates (including the Plaza Accord) have been most successful when they have a) corrected a large mispricing in markets and b) been backed by policies to correct the underlying causes of currency misalignment. (It is often forgotten that as part of the Plaza Accord, the US committed to significant fiscal retrenchment.)

In this sense, the various financial wheezes that have been suggested to weaken the dollar – from debt swaps to SWFs – are the market tail wagging the economic dog. None of them address the fundamental cause of trade imbalances.

The final way US policymakers might address imbalances is by targeting capital flows. While we've focused on the current account, every current account flow has a matching capital flow. The dollar’s global role drives demand for US assets, pushing up its value and hurting exports. Limiting capital inflows – such as through a withholding tax – could help narrow the current account deficit. If this also weakens the dollar, it could boost export competitiveness and improve the trade balance.

But this would not be costless. Capital controls would compromise the dollar’s reserve status, which rests in part on there being a large and liquid market for dollar assets that can be traded at low cost. And the dollar wouldn’t have to lose its reserve status to cause significant macroeconomic consequences; falling global appetite for dollar assets would, all other things being equal, increase US borrowing costs, leading to reduced domestic demand and lower output. And while the Fed could respond by lowering rates, this would only partly offset the squeeze on US consumers.

For all of Donald Trump’s complaints about America’s trade partners, the flip side of the US current account deficit is a willingness of foreigners to lend large amounts to the US, allowing it to consume more than it produces. Squeezing capital flows to America means squeezing consumption by Americans.

We’ll have more to say about reform of the global financial architecture in the coming weeks, but with the US now at full employment, the inescapable truth is that any short-term effort to make room for higher net exports would mean that consumption elsewhere in the economy must be reduced.

President Trump should be careful what he wishes for.

In case you missed it:

Join our UK team just after Wednesday’s statement from Chancellor Rachel Reeves to get answers to your questions about the UK fiscal outlook and its implications for markets. Register here for the online Drop-In briefing.

Canada’s election on 28th April has focused attention on the economic platforms of the leading candidates for PM. This recent analysis highlights the policy differences – and similarities – between Mark Carney and Pierre Poilievre and shows how they will each try to position Canada’s economy in the face of a brewing trade war.

Efforts to end the war in Ukraine have raised the prospect of sanctions relief for Russia. Nicholas Farr’s analysis shows how sanctions could bring some relief – not least in allowing Russian banks into the dollar system – but wouldn’t be a game-changer for Russia’s economic outlook.

Here’s what Deputy Chief North America Economist Stephen Brown told a client about the potential structure of a Trump reciprocal tariffs plan. It was just one of the direct questions that our economists answered for CE Essential and CE Advance clients last week via our economist Q&A forum.