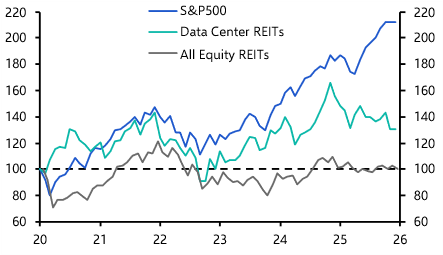

Towards the end of June, we raised our two-year forecasts for the S&P 500, advising clients that we now expect the benchmark to rise by around 50% between now and the end of 2025. It’s a bullish call – and one that takes into account a US recession later this year – that reflects the potential of artificial intelligence (AI), as well as investor enthusiasm around the technology’s adoption and development.

Our revised call provides a glimpse of what we think AI means for the global economy, not just in terms of how we think it will drive equity valuations in the next two years, but how it could shape everything from industrial processes to the US-China relationship in the coming decades, resulting in potentially momentous changes in economic outcomes.

This is part of a comprehensive view of the impact of AI that we’re currently preparing and intend to share with you in late September. We’re focussing on AI for this year’s Spotlight project for much the same reason that we chose to examine the fracturing of the global economy in 2022: it represents a potentially massive shift in the global economic narrative, but it’s one whose macro and market consequences are either not getting enough of the right attention, or are poorly understood.

The more we read about AI’s potential economic consequences, the more it becomes clear that the current research is overly focussed on specific areas, failing to provide a coherent and consistent framework for understanding its whole impact. As with our fracturing project, our upcoming work seeks to redress this by presenting a joined up view of the key ways that AI could change the global economy and shape market returns.

Avenues of exploration

One key issue relates to AI’s impact on economic growth and how the proceeds of that growth will be shared. Will it be spread throughout economies or concentrated among a small number of large tech companies? The fact that optimism around the AI’s potential has fuelled a rally in a handful of US tech stocks suggests that the market believes the latter is more likely than the former. If so, then the spread and adoption of AI will have big implications for regulators. After all, it was the accumulation of large monopoly profits during the “second industrial revolution” from the 1870s onwards that led to a wave of anti-trust legislation at the turn of the twentieth century.

There has also been intense debate around what AI could mean for growth and jobs – but less attention has been paid to its implications for inflation. The growing use of AI and associated technologies in the workplace represents a rise in the global economy’s supply potential. This in turn should be disinflationary – think of it as analogous to the increase in the global supply of labour following China’s integration into the world trading system, but this time with software taking the role of humans. Our Spotlight project will assess the potential impact on inflation, as well as the timeframe over which its impact could be felt, and what that could mean for monetary policy.

Attempts to quantify the effects of AI have also focussed on the implications for growth at what economists call the “technological frontier” – that is to say, the US. In addition to its impact on US growth, we’ll show what AI means for other advanced economies as well as its effects on emerging markets – including whether the ability to substitute AI for labour will undermine efforts to develop service sector-led growth models in parts of the emerging world. This would have significant economic implications most obviously for India, but also for the Philippines and Poland, which have become hubs for outsourced services.

China sits at the heart of the geo-economic question around AI’s impact. Will the development of large language models in China be held back by a smaller body of material on which to train them? Or will the potential for AI to transform industrial processes play to China’s strengths? More fundamentally, will AI become another faultline in the fracturing of the US-China relationship? If so, how will this affect the spread and transfer of AI technologies across the globe? The answer will have implications for investors, but also for politicians and policymakers.

Finally, any framework for thinking about the effects of AI needs to consider the implications for financial markets? Will the rising tide of productivity lift all boats and lead to strong earnings gains across all sectors? Or will the benefits of AI be captured by a small group of large tech firms? And what does history tell us about the risks of bubbles developing as a narrative around AI builds and investors seek to exploit perceived opportunities.

Plan of attack

Our team of economists is approaching each of these issues with the goal of forming a complete assessment of AI’s key economic implications and what those mean for all market participants – from asset managers and retirement funds, to private equity investors and wealth managers. After the publication of our report in September, virtual and in-person events planned for October will allow you to question the report’s authors and take our discussion forward. And clients of our Advance service will get exclusive access to interactive dashboards and the data underlying our work.

As with our work on fracturing, the initial report will act as a foundation for further analysis in response to shifting economic and market conditions – the report we plan to send you in September is a “starting gun” for a stream of analysis of AI’s macro implications, to be published across our regional and market services as the economic narrative and market response shifts.

We don’t pretend to have all the answers to the questions around AI’s impact but we do hope that our work provides that coherent and consistent framework necessary for thinking through its many consequences. We welcome your input too – if there’s an issue around AI’s emergence that you would like to see covered or have questions about the project, drop me an email.

In case you missed it:

- Senior Markets Economist Tom Mathews on our updated yield forecasts for Australia, New Zealand and Canada, whose central banks have – in their different ways – been pioneers in this monetary cycle.

- Tom is also on this week’s podcast, where he joins Ariane Curtis from our Global Economics team to discuss key takeaways from our Q3 Outlook reports.

- We looked at Beijing’s new export curbs on key materials in the manufacture of semiconductors from the perspective of the Chinese and Japanese economies, and commodities markets.