Neil Shearing

Group Chief Economist

The past couple of months has seen an upsurge in the number of analysts arguing that the renminbi will start to challenge the dollar’s position as the world’s reserve currency. But while the amount of world trade that is settled in renminbi is likely to increase over the coming years, this is unlikely to seriously threaten the dollar’s position at the heart of the global financial system.

Warnings of the imminent demise of the dollar are nothing new. In the 1990s analysts argued that the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency would be threatened by the yen. In the 2000s, the newly-established euro was supposedly going to challenge the dollar. Now it is the turn of the renminbi.

Part of the argument relates to economic heft. One can debate when China will overtake the US as the world’s largest economy (we are sceptical that it ever will). But it is clear that the US and China will remain the world’s two largest economies for the foreseeable future. It follows that China will naturally be a counterparty in a large share of cross-border transactions.

More importantly, the emergence of China as a strategic rival to the US is reshaping the global economic system in a way that is causing many to question dollar hegemony. The era of globalisation that swept across the world in the 1990s and 2000s is over. In its place is something that we have termed “global fracturing”. This is the idea that the world is splintering into two blocs: one that aligns primarily with the US and another that aligns primarily with China.

The argument goes that, as China pulls other economies into its orbit, it will increasingly push for trade within its bloc to be settled in renminbi – thus diminishing the use of the dollar. This has been given support by recent high-level meetings between Xi Jinping and other heads of state. In December, a meeting between Xi, Mohammed bin Salman and the leaders of the GCC announced what they called a “new paradigm of all-dimensional energy cooperation”, which included a push to settle energy trade between China and the Gulf in renminbi. And during a visit last month to Beijing, President Lula of Brazil called for an end to the dollar’s dominance in world trade. You don’t need to be a dollar bear to see a pattern emerging.

However, while global fracturing will fundamentally reshape the global economic and financial landscape over the coming decade, the consequences for the dollar are likely to be less dramatic than many now argue. This is for three reasons.

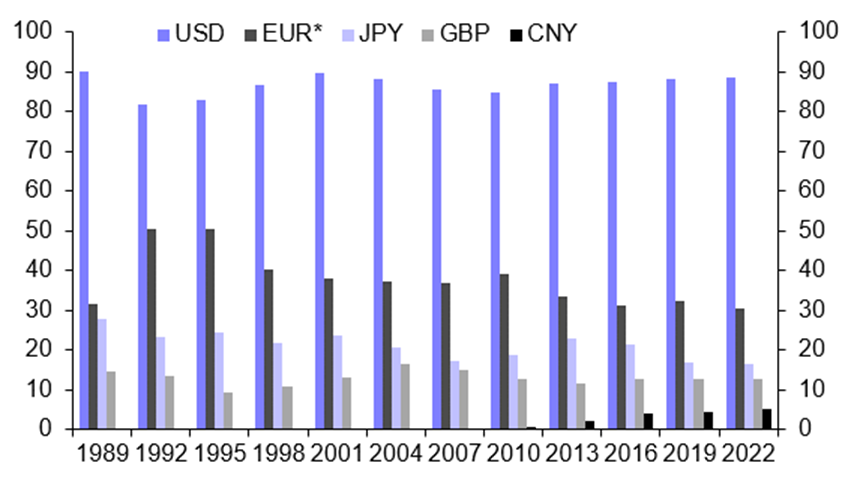

First, while much of the debate has focused on the dollar’s status as the world’s preeminent reserve currency, its financial and geopolitical influence stems principally from the dominant use of the dollar (and by extension the US financial system) in cross-border transactions. According to the triennial survey conducted by the BIS, 88% of transactions in the foreign exchange market in 2022 took place in dollars – almost exactly the same as in the 1980s, when the survey began. Meanwhile, only around 5% involve the renminbi. (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Share of Foreign Exchange Transactions (%) |

|

|

|

*Until 2001, sum of pre-euro EZ currencies Sources: BIS, Capital Economics |

What’s more, while trade between countries that align with China is growing, it still accounts for only 6% of global trade. In contrast, over 50% of global trade takes place within the US bloc, and over 80% of global trade involves a country that aligns with the US. (See Chart 2.) This trade will continue to be denominated overwhelmingly in US dollars. (Our methodology for assigning countries to blocs can be found here.)

|

|

|

|

| Source: Capital Economics |

Second, China’s high domestic savings rate means that it will tend to run a large current account surplus, which in turn will work against the renminbi becoming a serious rival to the dollar as a reserve currency. China’s capital controls also make it difficult to see the renminbi playing the role the dollar does. For the renminbi to become a major international currency, China would need to provide the rest of the world with large quantities of safe, liquid and convertible renminbi-denominated assets to serve as reserves for other central banks and collateral in financial markets. In turn, that would require a major shift in Beijing’s policy approach, giving up much of the political control over its economy that is a central feature of the current framework.

Finally, the dollar has several things working in its favour. For a currency to be widely used as an international medium of exchange, it must be readily and cheaply available around the world. That depends on foreigners being willing to hold it in large volumes: in other words, it must function as a store of value.

The dollar is not the only currency that could perform this role. But any alternative would need to share similar attributes: it would have to be backed by strong and stable institutions, and issued by a central bank that operated an open capital account. It is striking that despite the swathe of sanctions and asset freezes imposed on Russia over the past year, around half of its exports are still settled in either dollars or euros.

In addition, any currency that did have these characteristics would have to overcome the strong network effects that underpin the dollar’s global dominance.

All of this is likely to work against the emergence of a renminbi on a scale that threatens the dollar’s position. Wind the clock forward ten years and the most likely outcome is a more fragmented global financial system – but one that still has the US dollar at its core.

In case you missed it:

- Paul Ashworth argues that while in the end the collapse of First Republic was no great surprise, it is a reminder that further banking turmoil will continue to flare up periodically as interest rates rise.

- Simon MacAdam explains why our new FCIs suggest that financial conditions are tighter than traditional indices suggest.

- David Oxley explores the economic consequences of de-carbonising the shipping industry.