The elections that have concluded in major emerging economies over the past couple of weeks have been notable for several reasons: Mexico elected its first female president, Narendra Modi secured an historic third term as Prime Minister of India, albeit with a weaker mandate, and the ANC – which has dominated South Africa’s post-apartheid politics – is being forced into coalition government. Each result caused a shock and whipsawed their countries’ financial markets. But how important are these votes when it comes to the macroeconomic outlook?

A reality check

The truth is that elections do not typically have the significant and sustained impact on the macroeconomy that headlines would suggest (the rule applies in Europe too, where markets have reacted negatively to the shock outcome of parliamentary elections. See our initial take here). There are various reasons for this. In some cases, it is because the head of the executive is constrained by a lack of support in the legislature. This is happening to an extent in Argentina at the moment where President Milei’s plans to overhaul the economy have been stymied by an opposition-led congress.

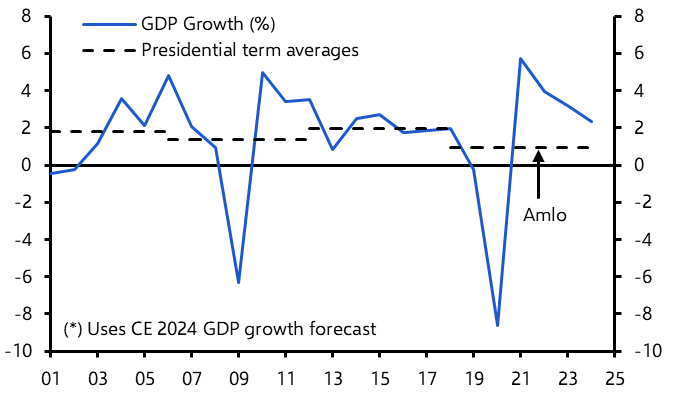

In others, it is because many of the more radical policies that are proposed on the campaign trail are diluted or abandoned once they come into contact with the realities of government. This has been the case in Mexico, where the outgoing president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (better known as Amlo) promised a radical leftward shift in economic policy during the previous election campaign in 2018, only to pursue orthodox fiscal policies while in government. (In fact, he found himself in the strange position of being urged to run looser fiscal policy by the IMF during the height of the Covid pandemic in 2020.) GDP growth in Mexico during his time in power was not much slower than that seen during the centre-right administrations that preceded him (and the recession during the pandemic explains a lot of the difference). (See Chart 1.)

|

Chart 1: Mexico GDP Growth (%) |

|

|

| Source: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

When elections do – and don’t – matter for the economy

Accordingly, whether it is the realities of governing or the straightjacket of the legislature, policy continuity – and growth continuity – is more common than political leaders would like to admit. Elections only matter from an economic perspective when they a) change the centre of gravity with respect to economic policy, b) deliver a government with a strong mandate and/or c) occur in an economy that urgently needs change.

This was the case in Brazil in 1994, where President Cardoso successfully shifted the political zeitgeist in favour of fiscal and monetary orthodoxy, which has since held over successive governments. But most EM governments now pursue conventional policies and have solid macro fundamentals. Peru, for example, has had five presidents in the past four years but this has not unsettled bond markets because the country’s economic fundamentals remain sound (a current account surplus, low levels of public debt) and there is for the most part a consensus across political parties in support of fiscal rectitude and pro-market policies.

What to make of EM Elections

Viewed through this lens, what should we make of elections in South Africa, India and Mexico fit into this framework? Mexico’s Claudia Sheinbaum got a very strong mandate – but for policy continuity. In so far as her larger majority in congress may allow her to effect change, the concern is that it will lead to an erosion of Mexico’s democratic institutions. This is the key area to watch over the coming years.

Of the three economies, South Africa’s, with its long-standing growth and fiscal problems, is in the most urgent need of change. The ANC has come out of the election severely weakened. It’s possible that this could lead it to form a coalition with the centre-right Democratic Alliance that provides renewed impetus for reform. But any such coalition would be fragile and lack a clear mandate. The most likely outcome is more of the same: weak growth and persistent concerns about the country’s fiscal trajectory.

Finally, sustaining India’s stellar growth record requires further progress on PM Modi’s reform agenda. His weaker showing has knocked those hopes, but he should still be able to work with a stable coalition. In fact, it’s possible that the need to govern in a more consensual manner will keep a check on Modi’s authoritarian leanings and allay concerns about the associated threat to India’s institutions. This would be positive from a long-run growth perspective.

Still, while each of these countries’ elections is important, they constitute only one factor affecting the economic outlook. After all, GDP growth – and financial market performance – is influenced by a multitude of economic, financial, technological, political and societal factors – many of which develop and evolve over decades and lie outside the immediate control of a single government.

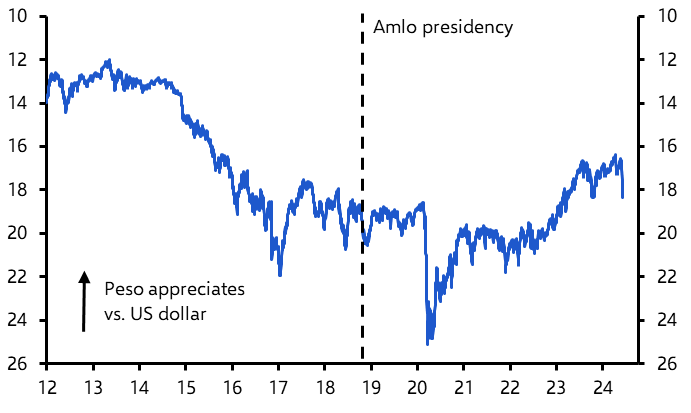

For instance, despite fears of an anti-market shift under Amlo, the Mexican peso has actually bucked a long-standing trend and appreciated against the dollar under his presidency. (See Chart 2.) This is partly because Amlo pursued less radical policies in government than had been feared. But the peso has also been supported by relatively high interest rates and hopes that Mexico will be the principal beneficiary of “near-shoring” as US-China fracturing deepens, neither of which is directly attributable to actions of the Amlo government.

|

Chart 2: Mexican Peso vs. US Dollar (Inverted) |

|

|

|

Source: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

US vote comes into focus

We suspect that the focus of EM investors will quickly shift to the US election later this year – and to its associated implications for US-China fracturing and the spillover effects from these geopolitical schisms.

As I set out in previous notes, the outcome of November’s election is unlikely to prevent the US and China from pulling further apart over the coming years – but it will affect the form that this fracturing takes. A victory for Donald Trump is likely to result in a greater focus on the use of tariffs as a policy tool and, in all likelihood, a widening of their application to include countries other than China. This would represent a broader shift towards protectionism in the US.

In contrast, a victory for Joe Biden would be more likely to result in a wider set of measures – including tariffs but also policies such as technology controls – focussed more narrowly on China itself.

Governments in the emerging world would prefer the latter over the former: not only are they less likely to be hit by a broad pushback against trade under a Biden administration, but the policy environment would also be more predictable. What’s more, the inclination towards a greater use of tariffs under a Trump administration would also point towards a stronger dollar, which has historically been a headwind for EM economies and markets.

We will have more to say on all of this as the election approaches. (Keep an eye on our dedicated election page, here.) For now, though, it says something about the economic and political development of emerging economies over the past three decades that the outcome of elections in America is at least as important as the outcome of elections at home.

Spotlight 2024

We’re launching our annual Spotlight project today at 1000 ET/1500 BST. It’s all about whether the US will continue to dominate the global economy, and whether its equities markets will continue to deliver the strongest returns. This project, which includes in-depth analysis and interactive data, addresses a host of fundamental questions about the global macro and markets outlook, including domestic political risks to the US economy, China’s chances of catching up and what to expect as this AI-fuelled bubble continues to inflate. If you’re in London on Tuesday, we’re holding a live discussion – details are here – as the first of several in-person and virtual events to mark the project’s release.