If there was any lingering doubt as to whether the ECB could cut rates ahead of the Fed, they have surely been extinguished by a series of recent remarks by central bankers. Speaking at an event in Amsterdam last week Klaas Knot, the head of the Dutch National Bank and ECB Board Member, said that over the coming months it would be “appropriate for us to gradually take our foot off the [monetary] brake”. Meanwhile, speaking at the same event, Jay Powell said that US policymakers were looking at “keeping policy at the current rate for a longer time than had been thought” given the “lack of progress” in returning inflation to 2% in recent months. The clear message from Knot was that the ECB did not have to wait for the Fed. This echoes that given by ECB President Christine Lagarde earlier this month, in which she argued that the central bank was “data dependent, not Fed dependent”.

A Dubious Idea

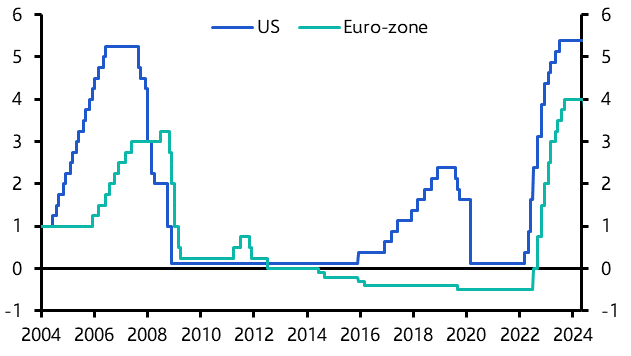

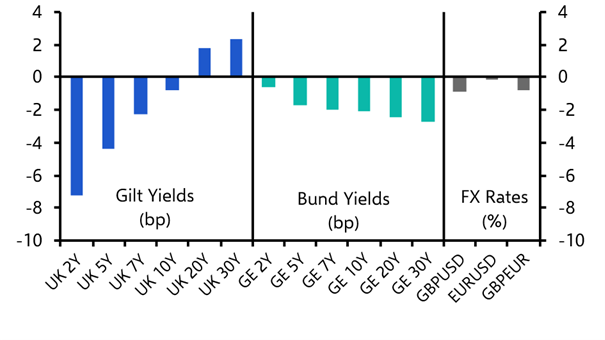

The idea that the ECB and other large central banks might require the Fed's blessing in order to lower interest rates was always a strange one. These are independent central banks setting monetary policy for major economies. They set policy according to domestic conditions and have a history of moving independently of the Fed. For example, the ECB cut rates by 50bps between 2014 and 2019 while the Fed raised rates by over 200bp. (See Chart 1.) Moreover, Sweden’s Riksbank has already cut interest rates in this cycle, lowering them by 25bps to 3.75% earlier this month. Likewise, the Swiss National Bank also cut rates earlier this year. (In both cases, we forecast the moves well ahead of the consensus.)

|

Chart 1: Policy Rates (%) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

The better question to ask, therefore, is not whether other central banks will have to wait for the Fed in order to cut interest rates, but whether the degree to which they are able to lower rates will be limited if the Fed keeps policy tighter for longer?

FOLLOW THE MONEY

The critical issue here is the effect that monetary policy differentials have on global capital flows and thus exchange rates and domestic inflation. In theory, were the ECB (or any other central bank) to set policy substantially looser than the Fed this would suck capital out of the euro-zone and push it into the US. This in turn should weaken the euro and strengthen the dollar – thus increasing imported inflation in the euro-zone. But does the theory stand up in practice?

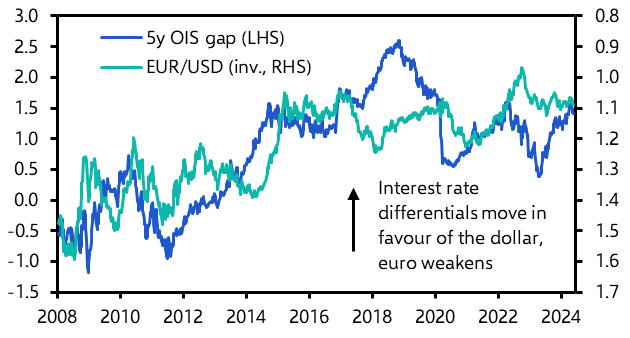

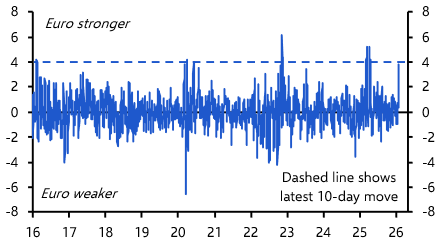

As Chart 2 shows, there is some correlation between euro-zone-US interest rate differentials and moves in the euro-dollar exchange rate, but the relationship is patchy and has broken down completely at various points since 2018. In other words, interest rate differentials are an important driver of currency moves – but they are far from the only factor at play.

|

Chart 2: Euro-Dollar Exchange Rate and 5yr Euro-US OIS Gap |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

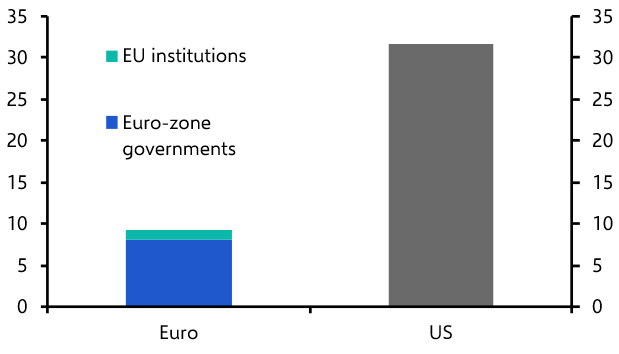

What’s more, to the extent that it is important, the ECB-Fed interest rate differential drives the euro-dollar exchange rate. But it is the trade-weighted exchange rate that matters for inflation. The dollar is an important part of any country's trade-weighted exchange rate, but if all other central banks loosen policy together then the fall in the trade-weighted exchange rate should be smaller than the fall in each currency against the dollar.

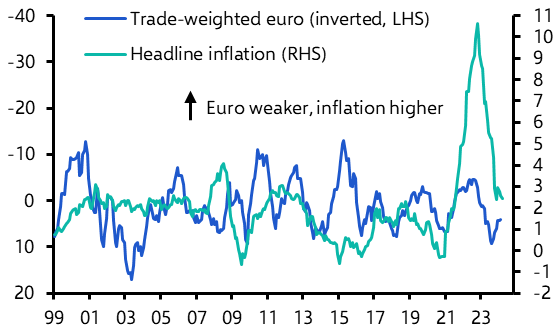

In any case, the relationship between the trade-weighted exchange rate and inflation is often weak. (See Chart 3.) This is for several reasons: only about 10-15% of CPI baskets in advanced economies outside the US constitute imported goods and services, and changes in the prices of these goods and services are often dampened within supply chains.

|

Chart 3: Euro-zone CPI Inflation and Trade-Weighted Euro (% y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

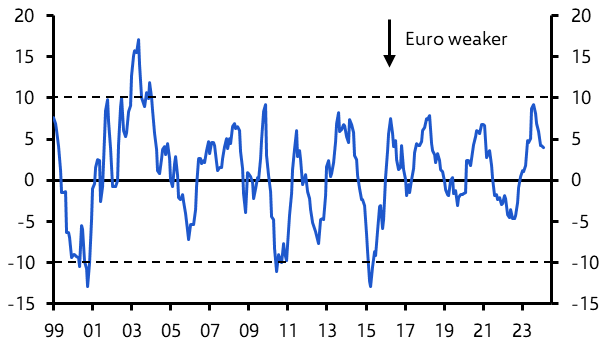

A 2020 study by the ECB found that a 10% depreciation in the trade-weighted euro would add just 0.4% to inflation after a year. Moves in the trade-weighted exchange rate of this magnitude are rare. (See Chart 4.)

|

Chart 4: Trade-Weighted Euro Exchange Rate (% y/y) |

|

|

|

Sources: Refinitiv, Capital Economics |

The real drivers of monetary policy

Central banks that manage fixed exchange rates against the dollar (predominantly in the Gulf) or of economies with high levels of foreign-currency denominated debt (Turkey, Argentina) must either move in lock-step with the Fed or closely mirror its moves. But for the central banks of major advanced economies the Fed is a relatively minor consideration when setting interest rates. The major determinant of policy is domestic conditions.

In this sense, there are good reasons for monetary policy in the euro-zone and UK to diverge from that of the US: the US economy is stronger, US fiscal policy is looser, and the structure of the US mortgage market has allowed households to lock in pandemic-era rates for longer, thus blunting the effects of policy tightening over the past two and a half years. All of this points to the need for higher interest rates in the US than in Europe.

The collapse in interest rates following the global financial crisis compressed interest rates across the developed world around the zero lower bound. But this was a historical anomaly. Since the euro-zone was founded in 1999, the ECB has consistently set interest rates below that of the Fed. As it happens, we suspect that, despite the hawkish rhetoric from Powell, the Fed will still cut interest rates later this year. But even if the Fed stands pat, it won’t prevent the ECB and Bank of England from lowering interest rates by more than the market currently expects.

In case you missed it:

Paul Dales argues that data due this week will herald the start of substantial falls in UK inflation.

Mark Williams argues that new US tariffs on imports from China matter – but not for the reason that you think.

Shilan Shah examines whether India could be a major winner from US China fracturing.