Will the recent weakness in a broad swathe of economic data be a flash in the pan or does it herald the start of a new global downturn? The answer is likely to depend in part on what happens to financial conditions.

Financial conditions is a somewhat esoteric term to describe how the prices of financial assets and the real economy interact with each other. The more financial conditions tighten, the more they drag on growth. Conversely, the more they ease, the more they support growth. Crucially, financial conditions have tightened in the run-up to most downturns in G7 economies.

The problem is that financial conditions themselves are difficult to measure. It is not simply a case of looking at policy interest rates. We also need to take account of other financial variables, including equity prices, corporate credit spreads and the exchange rate.

The picture is further muddied by the fact that some of the variables that are typically included in measures of financial conditions can give misleading signals about the outlook for the real economy. For example, government bond yields have fallen in recent weeks as investors have started to anticipate policy easing by central banks. All other things being equal, this should cause financial conditions to ease, which in turn should be supportive of growth. But in practice the relationship works the other way around – bond yields are falling precisely because of concerns about the outlook for growth.

The upshot is that financial conditions play an important role in determining growth prospects, but constructing and then interpreting indicators of financial conditions is difficult.

Last week, we published our own financial conditions indicators (or FCIs) for the US, euro-zone, UK and Japan. You can read more about the technical details here but a key point is that, in contrast to most FCIs, we adjust for the fact that some variables can give misleading signals about the implications for growth.

Three key messages stand out. First, FCIs across all four economies (and in particular the US and Europe) tend to move together. It’s rare that financial conditions in one major economy tighten without there being a similar tightening in the others.

Second, economic slowdowns tend to follow a sharp tightening of financial conditions, rather than when the FCIs pass a particular threshold. We should therefore put more emphasis on changes in our financial conditions indicators rather than their level.

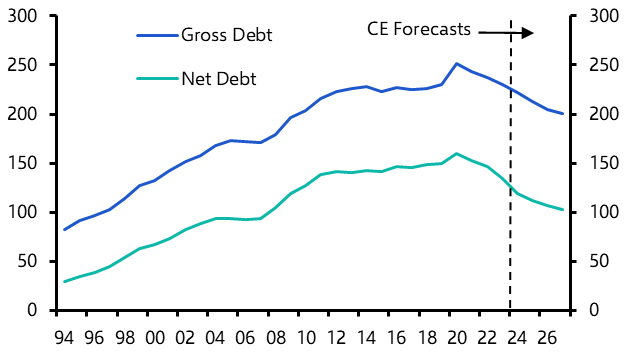

Finally, our FCIs show that conditions tightened in the major advanced economies in the final months of last year before stabilising in recent weeks as equity markets have rallied and credit spreads have narrowed. (See Chart.)

Chart: Capital Economics’ Financial Conditions Indices

What happens to financial conditions next will have a significant bearing on the prospects for economic growth this year. If the recent stabilisation is a sign of things to come then it becomes easier to believe that the weakness in the latest economic data will be a flash in the pan. By contrast, if financial conditions start to tighten once again (and our sense is that they probably will) then we’re likely to feel the consequences in terms of a further slowdown in growth over the coming quarters. Either way, this is the chart to watch over the coming months.

In case you missed it:

(Requires login)

- Our Chief Markets Economist, John Higgins, argues that even a reduction in the pace of QT is unlikely to prevent further falls in US equity markets.

- As the world economy slows, our Senior Economic Adviser, Vicky Redwood, looks at the lessons from Japan for other central banks.

- Our emerging markets team explains why EM central banks now have room to lower interest rates, even if their currencies come under pressure.