Sajid Javid’s abrupt departure as Chancellor of the Exchequer has raised expectations of a significant fiscal expansion in the UK. Among economists, meanwhile, it’s generated plenty of discussion about whether the UK’s fiscal rules - which were re-written by Javid only a few months ago - are set to be torn up once again. The more interesting question, in my view, is whether fiscal rules more generally continue to be of much value in today’s economy.

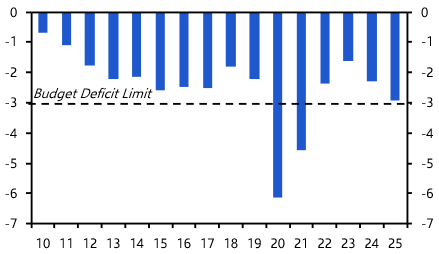

In theory, these rules serve two purposes. The first is that they provide a way for fiscally-prudent Finance Ministers to restrain other, more fiscally-profligate, parts of government. A well-designed fiscal rule should prevent governments from running excessive deficits in the good times so that when the bad times inevitably arrive the government has the “fiscal space” to loosen policy and support the economy.

A second, and related, purpose is to reassure investors of the government’s commitment to fiscal rectitude and thus, by anchoring bond yields at low levels, helps to reduce its borrowing costs.

However, as with so much in economics, the theory runs into at least two problems in practice. The first problem relates to the design of the rule. Central banks are generally given a rate of inflation to target with a tolerance band set around that target. This has the benefit of being both simple and transparent.

However, there are a multitude of different fiscal rules. Some governments target the overall budget balance and some target the budget balance after capital spending (the so-called current budget) or interest payments (the so-called primary budget). Some adjust for the effects of the economic cycle on the public finances while others don’t. Some ignore the budget position altogether and instead fix rules around the level of government debt.

The numerous forms of fiscal rules reflect the fact that there is no consensus among economists and policy makers about what exactly they should be targeting. The result is a mish-mash of different fiscal frameworks that makes it harder to coordinate policies across countries and more difficult for markets (and legislative oversight committees) to hold national governments to account.

In the end, this may matter less than you might think given the second practical problem, which is that fiscal rules tend to lack teeth. Governments set the rules and governments can change the rules. The fiscal rule is sacrosanct until such time as the government is at risk of breaching it, at which point it is usually replaced with a new one. In this respect, the situation is very different to rules governing monetary policy where central banks are given their mandate by governments. Fiscal discipline is, of course, still important. But this can’t be imposed by a set of rules that the government can change at will.

Issues around fiscal policy tend to play out at a national level. But there is also an international angle to this. The current plethora of rules across different countries produces sub-optimal fiscal policy at a global level.

As I’ve argued before, one way to generate a more sustainable recovery in global economic growth would be for countries running budget and current account surpluses to loosen the purse strings. But as things stand, these countries are resisting stimulus measures. Instead, it’s the deficit countries - primarily the US and the UK - that are embracing fiscal support.

This increases fiscal imbalances between economies and means that deficit countries are likely to have less capacity to provide fiscal support when the next global downturn hits. This is a particular problem given that monetary policy is now operating at or close to its limits in many economies, meaning fiscal policy will have to shoulder the burden of support in the next downturn.

So where does this leave us? It’s not obvious that fiscal rules are required to serve their original purpose in a new world of low growth, low inflation and structurally low interest rates. Even in the handful of emerging economies where concerns about fiscal mismanagement continue to inflate risk premia in bond markets, a budget rule is only as effective as the government’s resolve to meet it. Accordingly, we should worry less about the precise formulation of fiscal rules and focus more on narrowing fiscal imbalances between countries. This would serve the global economy better over the long run.

PS: As part of our commitment to improving our service to clients we are considering launching two new services: one focussed on currency markets (aimed at asset managers, traders and treasury teams) and another looking at the longer-term prospects for the global economy and financial markets (aimed at pension funds, endowment funds and insurance companies). If you have any views on what these services should (or shouldn’t cover) or would like to register an early interest in either then drop me an email – I’d be delighted to hear from you.

In case you missed it:

- Our Senior Economic Adviser, Vicky Redwood, looks at the prospects for a new wave of technological progress – and argues widespread pessimism may be misplaced.

- Our China team assesses the latest data on the impact of the coronavirus so far and concludes that the economy is likely to contract in Q1.

- Meanwhile, our EM team looks at the impact on supply chains, and concludes there is growing evidence of disruption, particularly in Emerging Asia.