The Weekly Briefing:

What's wrong with the UK economy (and what will it take to fix it)?

A Capital Economics podcast

16th May, 2023

The sick man of Europe. Broken Britain. Stagflation nation. The UK has had an unenviable post-pandemic economic recovery, lagging other advanced economies on growth but ahead of the pack when it comes to inflation. But how much of what ails the UK economy is cyclical? Are fundamental changes needed to put the economy on a surer footing and, if so, is there the political will to deliver them?

In this special episode of The Weekly Briefing, Chief UK Economist Paul Dales and Deputy Chief UK Economist Ruth Gregory speak to David Wilder about the UK’s near-term growth, inflation and policy outlook, as well as the longer-term issues that need to be addressed if the current gloomy narrative is going to be changed.

Transcript

David Wilder

Hello, and welcome to this special episode of the Capital Economics Weekly Briefing. It's 16th May. I'm David Wilder, and we're going to be hearing all about the outlook for the UK – otherwise known as ‘Broken Britain’, ‘the sick man of Europe’ or ‘Stagflation Nation’. The UK’s economic underperformance since the end of the pandemic been making headlines and fueling an increasingly heated public debate. But what's gone wrong with the UK economy, and when will it get right?

To sift out the cyclical from the structural and find out whether the UK deserves its current reputation, I'm joined by Chief UK Economist Paul Dales and Deputy Chief UK Economist Ruth Gregory. Ruth, I'd like to start with you and the inflation question. We're about a week away from UK’s April CPI release. Obviously, inflation has been the dominant global macro theme of the last 18 months or more. One striking part of that story has been what's been happening in the UK and you've done extensive analysis on UK inflation dynamics, including why it's been a standout among advanced economies. What's gone wrong here?

Ruth Gregory

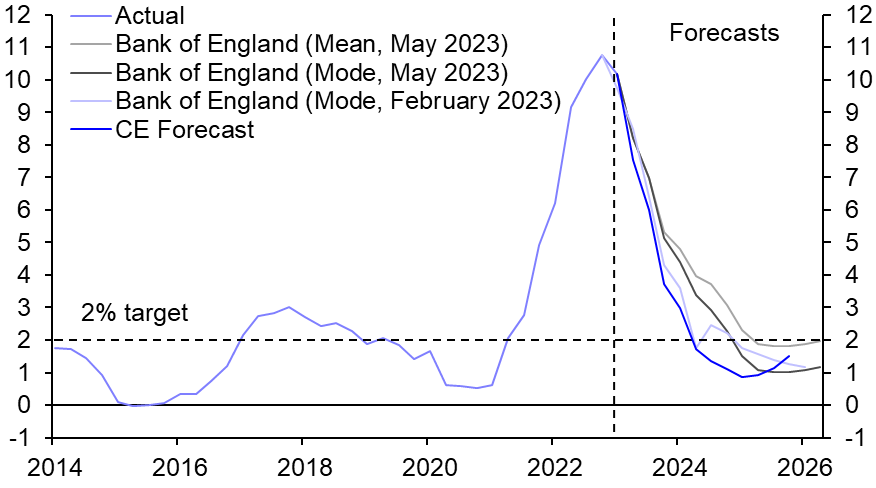

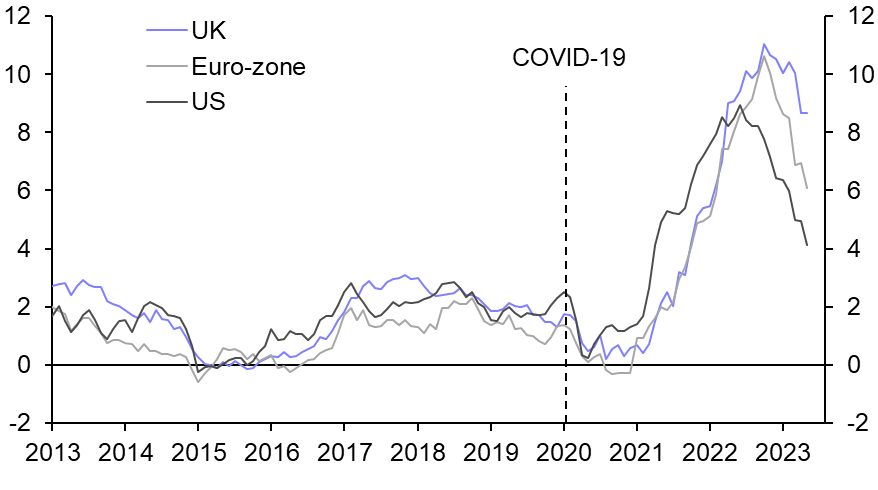

Yeah, I think inflation has been worryingly sticky. In the UK, it's striking that the UK has been lumbered with an inflation rate that's higher than all other Western European countries and further above the US rate than at any time since the current set of data began in 1989. I think there's two drivers of the UK’s higher inflation rate. The first is that, while energy has been a source of high inflation in every advanced economy, it has been a bigger problem for the UK and the eurozone than the US. And if you look at in the eurozone, some eurozone governments have capped energy prices sooner and by more than in the UK. So I think while energy price inflation peaked at 40%, for example, in the US, 44% in the eurozone, in the UK, it peaked at 59% and it has stayed comparatively high since. So that's part of the story. But I think it's not just an energy story. If you look at core inflation, which strips out energy and food items, that's currently running at 6.2% in the UK, whereas in the US it's 5.5%. And in the Eurozone, it's 5.6%. And I think this partly reflects the bigger rise in wage growth in the UK that’s supporting services inflation. And this reflects the UK in that it's unusual in the extent to which its labour force has declined since the pandemic. So I think, in short, the reason why inflation in the UK has risen further and stayed higher than elsewhere is because the UK has endured perhaps the worst of both worlds – a big energy shock like the eurozone and labour shortages that have been worse than the US.

David Wilder

And on a similar note, countless news stories about the UK recovery from the pandemic. How it's lagged the OECD average, the IMF projecting it's going to be the slowest growing of the G7 countries this year. What's behind that is? Is that what our analysis is showing as well?

Ruth Gregory

Yeah, I think there have been if you look back to the start of the pandemic, there have been two distinct periods, the contraction in the economy and the subsequent rebound in 2020, and 2021. And there have been different approaches to estimating things like public sector output which meant that the UK suffered a sharper contraction relative to, say, the US in 2020 but a stronger rebound in 2021 as that measurement effect unwound. If you look at the period, perhaps from the start of 2022 onwards, the UK has put in a much poorer performance than the eurozone in the US. You know, in the UK, in Q1 GDP was 0.5%. below its pre pandemic level. If you look at GDP in the Eurozone, it's 2.5%. above its pre pandemic level, and in the US it's 5.3% higher. So this underperformance I think does appear to partly reflect the weakness in real household spending, perhaps reflecting the UK’s higher and longer lasting inflation problem.

David Wilder

What does the near term outlook look like for the UK on the inflation and growth fronts?

Ruth Gregory

Well, I think I think the good news is that the inflation backdrop will soon look a bit more a bit more comfortable. We'll see the big rise in utility prices back in April 2022 dropping out of the annual comparison this April. So that means that inflation will probably fall quite sharply from 10% now to around 8% in April. And I think that may give the Bank of England perhaps a bit more confidence in its forecast that inflationary pressures will gradually subside. And I think at the same time, perhaps the higher interest rates go, the more conscious the Bank will be that the you know, there is a big drag on activity and price pressures in the pipeline. So, our forecast is that at 4.5%, Bank Rate is now at its peak and the hiking phase of the cycle is over. But our forecast is based on an expectation that there will be a bit more weakness in the economy that will weaken price and wage pressures and bring inflation back down to the 2% target. I think the risk is if this weakness in economic activity doesn't emerge and there's more signs of resilience in activity then perhaps interest rates may have to rise a bit further. So I guess we wouldn't push back too hard against some forecasters’ expectations that interest rates may rise to 4.75% or 5%.

David Wilder

And what about the recession question, based on recent data? Do we still think a recession is likely for the UK economy?

Ruth Gregory

Yeah it's a good question. I guess, like most economists, we have been surprised the economy has avoided a recession so far. You know, we know that the surge in inflation meant that real incomes, real household incomes, fell by a large 1.7% last year. And we've seen the fastest and largest rise in interest rates since the late 1980s. But so far, the UK economy seems to have come through this period of high inflation and high interest rates without experiencing a recession. And I think perhaps what's happened is the economy has been hit by these drags. But there have been a number of offsets, including fast wage growth, the government handouts, which have supported households’ real incomes. And more recently, we've seen a plunge in wholesale gas prices, which has reduced the drag on household income. So I think, you know, I guess the good news is that the worst of the falls in household real incomes from high inflation is now behind us. But the bad news is that the full drag from higher interest rates has yet to be felt and some of those offsets, in terms of the support provided to household incomes from the government, will fade. So I think it may be too early to sound the all-clear. And there is still a risk that there may be a recession later this year.

David Wilder

And given our understanding of UK inflation dynamics at the moment, to what extent can we argue that recession is necessary – as perverse as that sounds – to purge inflation from the economy?

Ruth Gregory

Yeah so I mean, our forecast is that there will be a mild recession later this year, and that will weaken domestic price and wage pressures back to levels consistent with the Bank of England's 2% inflation target. But I think there's a real risk that if a recession doesn't emerge, and if there isn't any, if there isn't any further weakness, or the recent resilience in real activity is it you know, continues to translate into stronger domestic price pressures, then interest rates may have to rise a bit further. So I think that's one reason why we wouldn't push back too hard against some forecasters expectations and current market pricing for interest rates to perhaps rise a little bit further from 4.5% now to 4.75% or a peak of 5%.

David Wilder

But just to stress, you're talking mild recession. What does a mild recession look like compared to recent downturns?

Ruth Gregory

Yeah, so we're expecting a mild recession involving a peak to trough fall in real GDP of around 1%. And that would be very small in comparison to previous recessions.

David Wilder

But you could also have a period of just really low growth that leads to weakness in the labour market that does the work to squeeze inflation out of the system, couldn't you? Yeah,

Ruth Gregory

I mean, this is this is the really difficult question at the moment, do we need to see outright falls in economic activity and a recession – which is defined as two quarters of negative growth – in order to bring inflation back down to the 2% target? And I think that there is a question here, because we have seen more persistence in price and wage setting and more persistence in second round effects. And it's not clear there's a huge amount of uncertainty about how much weakness in the economy will be required to bring inflation back down to the 2% target.

David Wilder

I guess the current growth settings aren't conducive to inflation just naturally burning itself out?

David Wilder

Yeah. So the Bank of England has in its latest forecast in the in the May monetary policy report, it's got this “immaculate disinflation” story where inflation and returns back down to the 2% target, actually below the 2% target, without there being a recession in the economy. I think there's a question about whether that's too good to be true: can inflation fall back quickly? And the Bank of England does stress that the risks to its inflation forecast are significantly skewed to the upside if we were to see these second round effects persist for a little bit longer.

David Wilder

And what about the flip side of that you talked about weakness coming through into economic activity. At what point do you think the Bank is going to cut rates?

David Wilder

Yeah, I think I think that's a really good question. I think whatever the peak in interest rates, we don't think that rates will be cut quickly. You know, we don't think the Bank of England will cut interest rates this year. The Bank’s still very worried about domestic inflationary pressures being too high and those pressures looking too persistent. And I think the drivers of those inflationary pressures such as the tight labour market do remain in place. So it's certainly the case that inflation will fall sharply this year. We think it will ease from 10% now to around 4% by the end of the year. But I think it's unlikely that wage growth and core inflation will ease quite as sharply as overall inflation. So I think it may take some time for the Bank to conclude that domestic inflationary pressures are easing to rates that are consistent with the Bank of England’s 2% inflation target, and we don't think that's likely to happen within, you know, within the next eight months. So, you know, we don't think that interest rates will be cut until the first half of next year.

David Wilder

Paul, I’d like to bring you in now if I can. Ruth has addressed these cyclical factors driving the UK’s near-term outlook. But what about the more sort of fundamental structural issues affecting the economy? I'd like to start with Brexit. That 2016 vote doesn't seem to have healed anything in the body politic does it? And it's now being blamed for this whole list of ills in the UK economy. How has or hasn't Brexit affected the UK post-pandemic narrative?

Paul Dales

I'm not sure that Brexit has been the main issue driving the stagflation environment that Ruth has described, by which we mean a combination of high inflation and very subdued economic growth. But it's certainly been a contributing factor. So we're seven years on from the Brexit vote in 2016, and two years on from the implementation of Brexit. So we do have a fair amount of actual evidence to look at now. And when we do that, there's three areas where it seems to have played a part. The first is a constraint in the supply of labour. Now, I don't mean in the actual absolute amount of labour capacity in the UK, because there hasn't actually been a very, very big decline in net migration. In fact, the migration numbers have actually been surprisingly strong. But what has happened is there's been a shift in the composition away from migrants coming in from the EU, and being replaced by migrants coming in from the non-EU. And those workers have different characteristics and that's contributed to some mismatch in the labour market which, to some extent, has boosted wage growth and fed that inflationary environment that Ruth discussed.

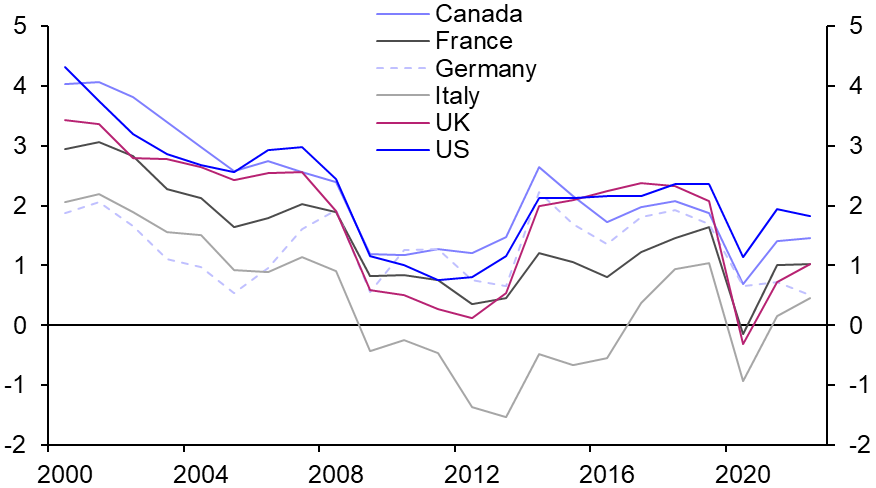

The second area is that business investment has been particularly weak in the UK since the referendum vote. So, if you even include government investment, and that's probably being a bit generous, total investment in the UK is about 10% higher than back in 2016, whereas in all other G7 nations, it's about 15% higher. And I think that's got a lot to do with the extra uncertainty generated by Brexit. And the third area is that there's been higher trade barriers, and unsurprisingly, that has held back UK exports relative to some other countries. So relative to the 2018 average, UK real exports are about 5% below that level, whereas in the US they are 2% above and in the euro zone, it's closer to 12% above. So I don't think this is the be all and end all. But it has certainly held back UK growth to some degree and added to some of the inflation pressures as well. And those trends probably aren't going to disappear very quickly either.

David Wilder

So these aren't just the pains of adjustment to a post-Brexit world, and something that a few well drafted trade and access deals will sort out and put the economy into a better position?

Paul Dales

I don't think so, no. I think there's some elements of that where businesses can adapt, have adapted and will continue to adapt. So these effects should fade over time. But the effects are still going to be there. And essentially, what the UK’s got at the moment is a problem of relatively high inflation, slow growth in its labour force and slow productivity growth. And the last two of those, I think, are certainly things that will take a long time to fix if indeed, they can be fixed

David Wilder

Segues nicely to vote to my next question. You kind of touched on it a bit there. This has been a core theme of our UK analysis in recent years. I know you've written about it, and I know a lot of economists across our company have written about this dangerous focus on short term fixes that fail to address these core structural problems in the UK economy. Paul, it's a big question, but I wonder if you could condense it down: what does a prescription for fixing the UK economy look like?

Paul Dales

Well, I think you've got to do two things really. We need to see labour force grow at a faster rate, and we need faster productivity growth. Now that's not new. We all know that. But trying to achieve it is really challenging. And what governments tend to do is they tend to pick one or two things to focus on, and they go hell for leather on that. But as we explained in a report we published in early March, what you actually need is some really joined up thinking and some acknowledgement of how all the different factors and parts of the economy interrelate with each other. And that's where I think politicians seem to fall down. So at the moment, there's this huge focus on migration, understandably.

But as well as a political angle here there's an economic angle and often those things contrast and conflict. But what you really essentially need is we need to be in a situation where the government can help to encourage people to make themselves more available to work. And they can encourage businesses to invest so that they can improve productivity in the future. The current government hasn't really done a very, very good job of that. In some sense, it’s spent more time in-fighting rather than actually devising policies that might help the long term future of the UK economy. So it's a really, really big challenge. There are certainly things to be done. But I think you need real holistic thinking in order to pull some levers that actually generate proper results rather than just political noise.

David Wilder

That March report you mentioned, it cites the examples of the Atlee and Thatcher governments as two moments in modern British political history where there was appetite for change and administrations that had the willingness and ability to capitalise upon that. We've got a general election scheduled to be held in just over 18 months from now, at the very latest. Would a Labour Government, do you think, be able to institute that kind of change that you talk about? And if not, what does that hold for the UK economy over the next 5-10 years?

Paul Dales

Well, the perception with the Labour governments that it’s not quite as good at managing the economy than the Conservatives is actually false. We've looked back at this in detail and Labour's economic record is no worse than the conservatives. So I’d probably push back against that. And a Labour government, if there is one, would surely have learned from the Truss-Kwarteng issues over fiscal policy and would probably run quite a disciplined fiscal situation.

I think it's true that the composition of fiscal policy would change. Perhaps there'd be higher public spending, financed by higher taxes on the wealthy and also businesses. But what really needs to be addressed is supply-side reforms. So these are those issues I've talked about of raising investment, raising the growth of the labour force and raising productivity. And I think Labour, you might be able to make some progress there, perhaps, you know if they're more united, if they have a greater majority, then they might be able to spend more time actually formulating and implementing policies rather than just fighting amongst each other. But there are some gaps. I mean, we don't really know what the details are on Labour's plans for migration or their plans for planning reforms. And the bottom line is that supply-side reforms are always unpopular and they are a really long slog. And it's hard to see any government really wanting to take them on and being particularly successful. And the really big difference between the examples that you mentioned earlier is that Thatcher, for example, had…there was lots of scope for supply side reforms because she was able to privatise lots of the public sector, and dramatically changed the way trade unions influence the economy. There's less scope for those kinds of benefits now.

Now, none of this is to say that we're terribly downbeat on the medium term outlook for the UK economy. In fact, we are relatively more optimistic than most. We think that the UK economy will probably still be able to grow by around 1.5% a year over the next 20 years or so, which is a bit more than most people expect. But that's largely due to global trends and the development of digital revolution boosting productivity growth rather than the behaviour of UK politicians. So our relative outlook on the UK, the reason why it's pretty good, is despite the politicians – not because of them.

David Wilder

That Paul Dales and Ruth Gregory talking about the UK economic outlook. I'll link to all their key recent analysis on the podcast page of our website – that's capital economics.com. And the website is also where you can find our complete coverage of the UK economy and markets. But until next time, goodbye.