Autumn Budget aftermath

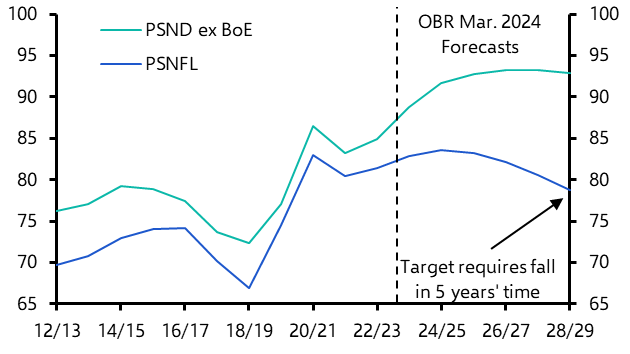

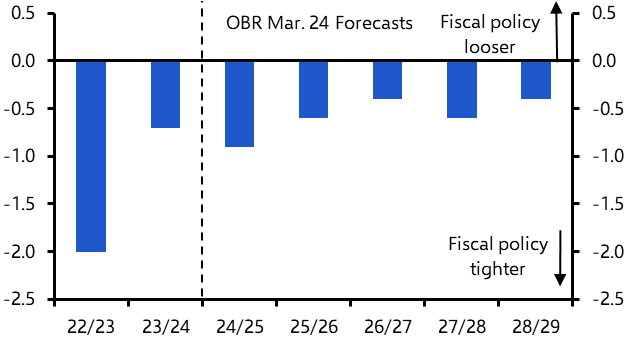

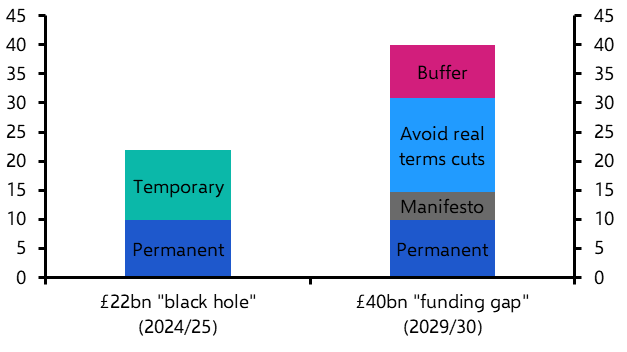

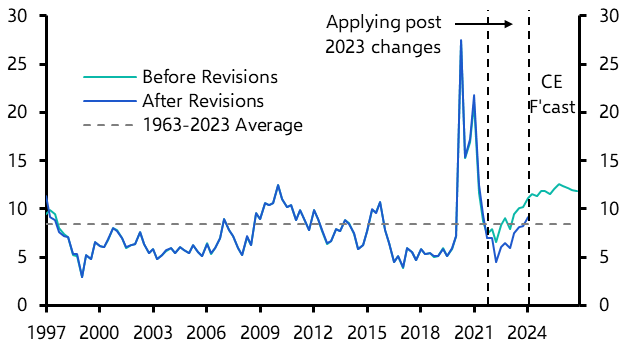

Key analysis on the macro impact of the Chancellor's tax, borrowing and spending plans

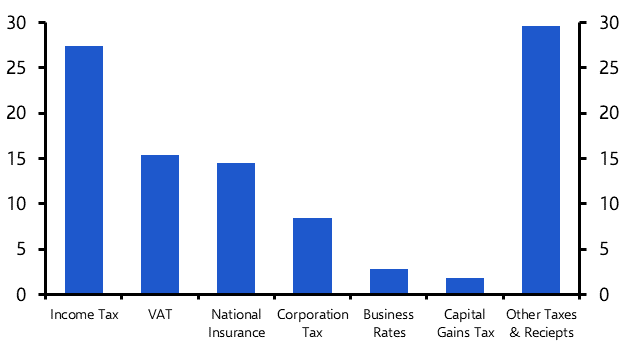

UK 2024 Budget Preview

Exclusive preview of Rachel Reeves’ UK 2024 Autumn statement

How will Rachel Reeves' debut Budget balance tax, spending, and borrowing to drive growth while maintaining market confidence? Read our in-depth report for insights on what to expect.

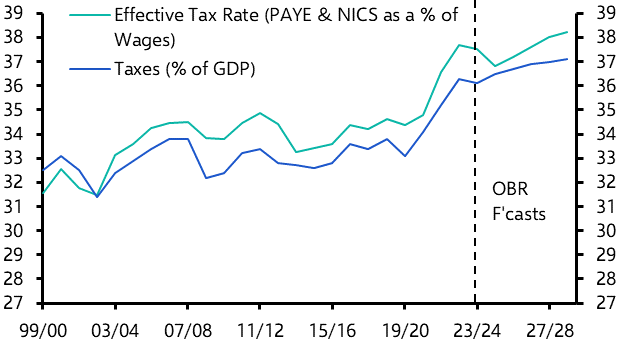

Fiscal Headroom Monitor

See how market interest rate expectations influence the fiscal policy space available to Rachel Reeves