A combination of the Federal Reserve’s fight against inflation, the UK’s self-inflicted budget crisis, and Xi Jinping’s efforts to consolidate power at China’s 20th Party Congress has kept Europe out of the headlines in recent weeks. But all is not well in the region. A recession is looming and it will be deeper than most analysts expect. Our forecast that the euro-zone economy will contract by 1.8% in 2023 puts us right at the bottom of the consensus range. The response of governments will determine whether a bad situation is made much worse.

What ails the euro-zone

There are two drivers of Europe’s looming recession. The first is the huge deterioration in the region’s terms of trade caused by the surge in the price of its energy and food imports. This has been larger than what the region experienced during the twin oil crises of the 1970s, and it is manifesting itself in big falls in household real incomes. We forecast that real household disposable income will contract by between 2% and 4% in the major euro-zone economies next year. At the same time, energy intensive industries such as metallurgy and chemical processing are being squeezed. This is hitting Germany’s economy particularly hard and the effect is likely to be permanent as well as cyclical should the energy shock accelerate structural decline in some parts of these industries.

The second driver of Europe's downturn is that, in response to this year’s inflationary surge, the European Central Bank is raising interest rates and tightening monetary conditions. We’ll hear more from policymakers when they meet this Thursday, but recent communications suggest that they want to return interest rates to what they believe is a “neutral” level as quickly as possible and then take stock. The markets are pricing in a 75bp increase in interest rates this week, but we think a 100bp hike is possible (register here for our 25th October preview of the meeting). This would take it to 1.75%. We then think it will be raised to 2.25% by the end of this year and a peak of 3% by mid-2023.

There is already evidence that some interest rate-sensitive parts of the economy are starting to suffer. Housing markets are fragile, with residential construction activity turning down across the euro-zone’s major economies and house prices beginning to fall in those countries that previously experienced the largest increases (notably the Netherlands and Germany). Banks in these countries look able to weather a property downturn without it infecting the broader financial system in the same way that it did during the Global Financial Crisis in 2007. But housing weakness will hit the region’s construction sector hard as well as squeezing household net wealth.

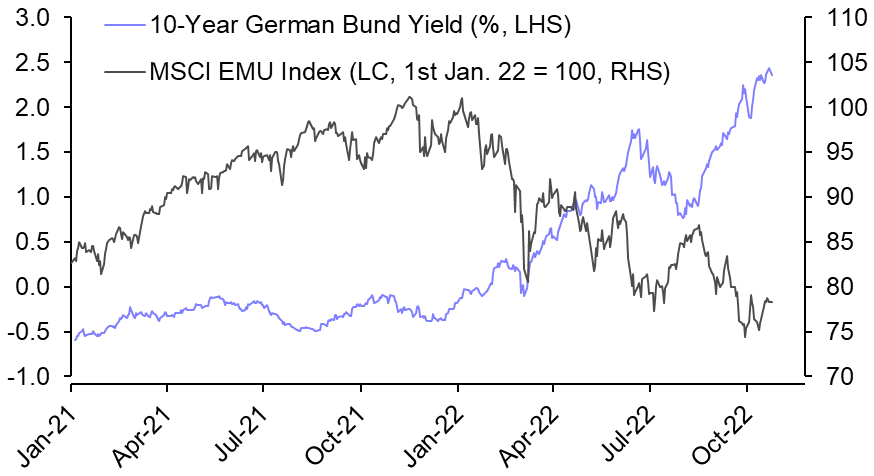

Given the extent to which the economic outlook has soured, it is perhaps surprising that there have not been larger strains in Europe’s financial markets. Stock markets have fallen by around 20% from their peak in January this year, and bond yields have risen. (See Chart 1.) But unlike other market sell-offs in the region’s recent past, there is no sense of crisis.

|

Chart 1: Germany 10-year bunds & MSCI EMU Index |

|

|

|

Source: Capital Economics, Rrefinitiv |

Expanded toolkit

One reason for this is that the ECB is now a more credible backstop to the euro-zone’s sovereign bond markets. The Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), which was introduced earlier this year, gives the ECB broad discretion to purchase government bonds in the event of a widening in spreads that it deems to be “unwarranted”. Meanwhile, Outright Monetary Transactions (OMTs), which were introduced during the euro-zone crisis last decade, allow the central bank to purchase government bonds in the event that policy errors lead to a widening in spreads that it believes threatens financial stability. The euro-zone remains more fragile than countries such as the US or UK, where national central banks stand directly behind sovereign bond markets, but the ECB’s expanded toolkit means that compared to a few years ago fragmentation risks have been reduced.

More fundamentally, euro-zone governments have avoided the reckless fiscal policies that triggered the UK’s self-inflicted crisis. As ever, Italy remains the weak link. But Giorgia Meloni’s new government has so far talked a reasonably sensible economic game – she has jettisoned the worst of the anti-EU rhetoric that she espoused in the past and has appointed Giancarlo Giorgetti, a fiscal moderate, as Finance Minister.

Fiscal risks

Yet it is easy to envisage how things could start to go wrong. Germany's 200bn-euro domestic energy support package has prompted a backlash among euro-zone countries with less fiscal space. But the German government has continued to voice scepticism around using jointly-issued sovereign bonds to finance region-wide energy support packages.

Unless Germany softens its position, euro-zone member states will be pressured to continue to use national measures to support households and industry against high energy prices. In countries where bond yields are high, that will imply a larger burden for the public finances. That includes Italy, whose new government remains an unknown quantity which has yet to be tested in office.

A unified response to the war in Ukraine has created a common purpose within Europe that in turn has helped to prevent strains from emerging in financial markets. But a lot of economic pain has to be felt and a long, hard winter lies ahead.

If European solidarity gives way to fiscal populism it will become much harder.

What you may have missed:

- Our Q4 China Economic Outlook paints a bleak picture of an economy continuing to be weighed down by the government’s zero-COVID policy.

- Andrew Wishart, who leads our UK Housing coverage, showed why don’t think the UK property sector will trigger a banking crisis, even as it helps drag the economy into recession.

- As part of our new, dedicated Climate Economics coverage, Chief Emerging Markets Economist William Jackson explained what Brazil’s presidential election outcome could mean for the pace of deforestation.